Survey says

Parents who have one child with autism would like a genetic test to predict their next child’s risk of the disorder. But it’s not clear how well the tests work.

Genetic tests for common forms of autism still have a way to go before they can be used to diagnose the disorder. (The tests used by doctors today detect rare variants responsible for a minority of autism cases, and are typically used after diagnosis.)

But companies are already starting to offer tests based on common variants — those that affect more than five percent of the population.

A new survey, sponsored by IntegraGen, one such company, shows that 80 percent of parents who have one child with autism would use a genetic test to predict autism risk in a second child. These so-called baby sibs have an approximately 20-fold increased risk of developing autism compared with the general population.

The results, published 28 November in Clinical Pediatrics, aren’t surprising. Parents most often reported that they want this type of test in order to get an earlier diagnosis and therefore earlier intervention.

One might expect that given their increased risk, siblings of children with autism would be diagnosed earlier than average. But the survey found this wasn’t the case. The average age of diagnosis for high-risk children in the study was 4.7 years, compared with the average of 4.4 years reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Most parents reported that they suspected their child had a developmental delay before they were 2 years old but that it took an average of three additional years to get an official diagnosis.

The study is based on an Internet survey of 162 parents who have at least one child with autism and one child younger than 48 months without an autism diagnosis. The small numbers make it difficult to predict how broadly accurate the findings are.

IntegraGen’s test, which costs almost $3,000, looks for 65 single-nucleotide variants, or SNPs, in the younger sibling to predict autism risk. But each of these SNPs only marginally raises risk. Nor is the test sensitive, missing 85 percent of children who will go on to develop the disorder.

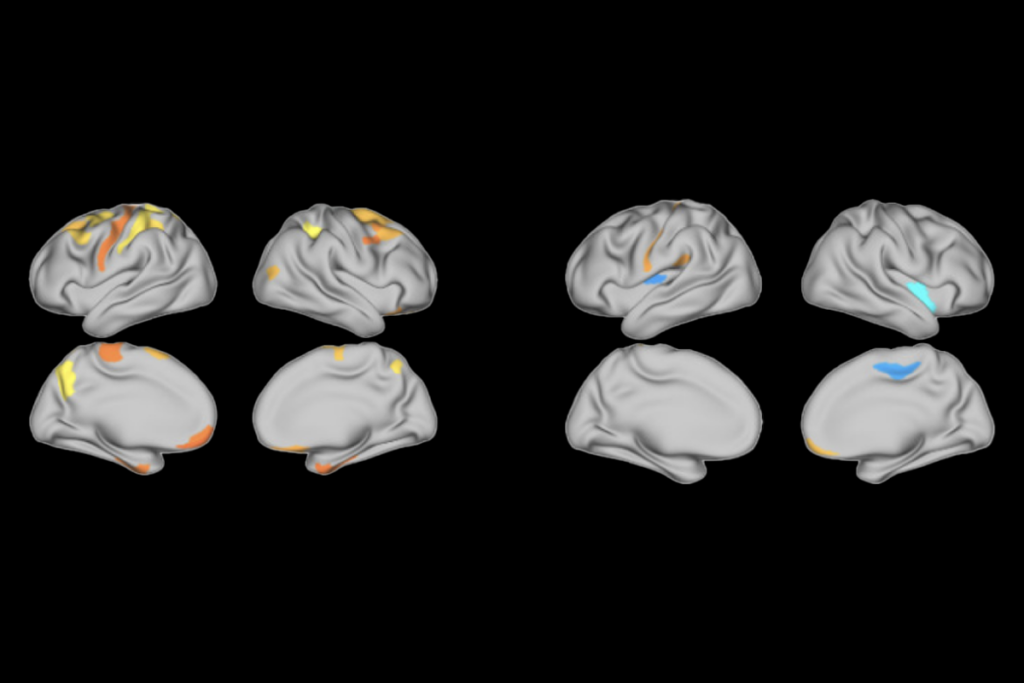

A number of studies are looking for risk predictors in baby sibs, such as differences in brain activity, gaze or other factors. A combination of genetic factors and physiological or behavioral measures is likely to prove most reliable at predicting which babies will go on to develop autism.

Recommended reading

Latest iteration of U.S. federal autism committee comes under fire

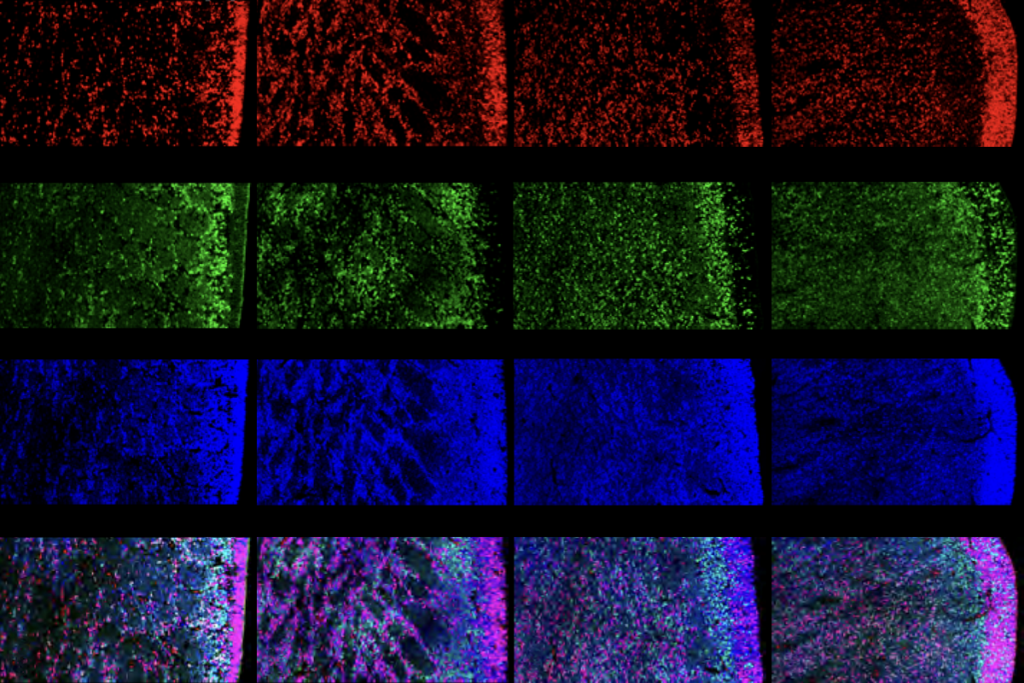

‘Tour de force’ study flags fount of interneurons in human brain

FDA website no longer warns against bogus autism therapies, and more

Explore more from The Transmitter

Betting blind on AI and the scientific mind