Genetic tests for autism debut amid concerns about validity

A genetic panel intended to predict the risk of developing autism debuted for clinical use in April, while another is in commercial development and a third was published in Molecular Psychiatry in September. But some experts are concerned, saying the tests are based on preliminary scientific evidence.

A genetic panel intended to predict the risk of developing autism debuted for clinical use in April, while another is in commercial development and a third was published in Molecular Psychiatry in September1. But some experts are concerned, saying the tests are based on preliminary scientific evidence.

Several tests for autism are already in widespread clinical use, but those detect rare genetic variants that account for only a small percentage of cases.

The new tests instead analyze combinations of common markers. Two of the new tests detect single-gene variants, and the third looks at expression patterns of several hundred genes in blood.

As the cost of sequencing continues to plummet, experts say families are likely to be offered a dizzying array of similar tests that claim to screen for autism.

The average child with autism is diagnosed at age 4 — several years after symptoms emerge and after behavioral interventions are thought to be most effective.

For this reason, scientists have been searching for an early and reliable biomarker of the disorder. So far, however, studies of several thousand people with autism or other psychiatric disorders have failed to find any predictive genetic combinations2.

“We need to be more solid on this data before you’re giving a flyer to a family and saying, ‘Spend some money and this might give you some information,’” says Richard Anney, assistant professor of neurodevelopmental molecular genetics at Trinity College Dublin, who was not involved in the new tests.

Common risk:

Many specialized clinics already offer genetic tests for rare forms of autism. The tests typically rely on chromosomal microarray analysis, which identifies large DNA deletions or duplications. This type of genetic glitch, however, appears in only about ten percent of people with the disorder.

In April, the French biotech company IntegraGen debuted a genetic test that looks instead at common variants — called single-nucleotide polymorphisms, or SNPs — that are more likely to crop up in individuals with autism than in controls. Each SNP confers only a slightly increased risk of autism, and many people who carry autism-linked SNPs do not have the disorder.

IntegraGen’s test is tailored to families who already have one child with autism and want to gauge the risk for a second child. Among younger siblings of children with autism, 1 out of 5 develop the disorder, compared with 1 in 88 in the general population. The $2,895 test purports to pin down the risk more precisely by screening for combinations — one for boys, another for girls — of 65 SNPs.

The test places younger siblings into one of several risk categories, based on the SNPs they carry: For example, boys in the highest category of risk have a 59 percent chance of developing autism.

The test has a different level of accuracy for each risk category. For the highest risk group, for example, the test has about 95 percent ‘specificity’ for correctly identifying children who will not develop autism. This category has 15 percent ‘sensitivity’ for correctly identifying the children who do develop autism, meaning that it misses 85 percent of children who will develop autism.

However, the relatively high specificity means that few children are falsely identified as being at risk for the disorder. As a result, the test brings attention to children who are most in need of early intervention, says Bernard Courtieu, chairman and chief executive officer of IntegraGen.

The company first tested the predictive value of its SNPs on 545 families from the Autism Genetic Resource Exchange (AGRE), a biobank of ‘multiplex’ families, which have more than one child with autism. The researchers then validated the findings in a second group of 627 families. They presented the data for 57 of the SNPs in May at the International Meeting for Autism Research in Toronto, but have not yet published the findings.

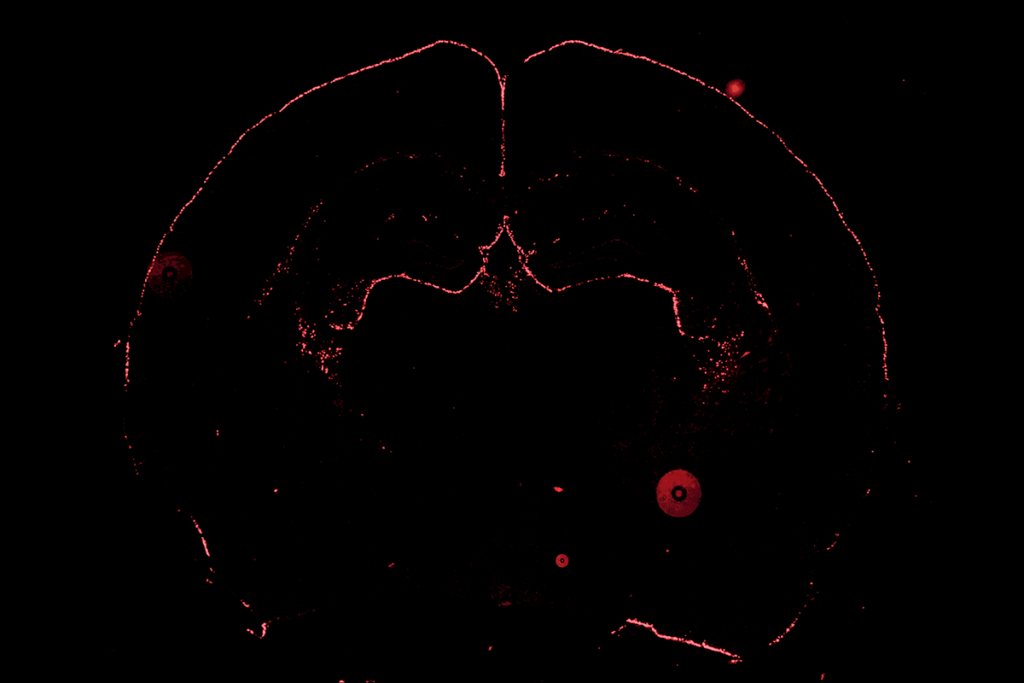

IntegraGen’s team pinpointed the SNPs from the AGRE database, and then prioritized SNPs that showed relatively high statistical significance in several large association studies. The SNPs are located in genes — such as ASTN2, CADM1, GRIN2A, NTRK3 and PCDH10, to name a few — that are expressed in the brain and involved in autism-linked pathways.

IntegraGen and others are also developing screens for children with no family history of the disorder. For example, SynapDX, a company located outside Boston, is working on an autism test that measures the expression of hundreds of genes in the blood. The test is not yet commercially available but has performed well in clinical studies, according to the company’s president.

Contentious combinations:

Independent experts approached by SFARI.org were reluctant to comment on the validity of IntegraGen’s test, as the methodology is unpublished. But based on other studies, they say it’s doubtful that combinations of SNPs can accurately predict autism.

For instance, an Australian group reported in September that a predictive panel of 237 SNPs in 146 genes can predict autism with 70 percent accuracy1. The researchers identified the SNPs by screening samples from AGRE, and then validated them in two other datasets.

One set of samples is from the Simons Simplex Collection, a biobank of families that have only one child with autism, sponsored by SFARI.org’s parent organization. The second batch of samples is from a Wellcome Trust cohort of healthy British people born in 1958.

Anney notes that the study may suffer from a ‘gene-size effect.’ Because of a quirk of the methods used, SNPs that fall in large genes are weighted more heavily even when they don’t necessarily confer more risk. He also notes that whereas the autism samples are from Americans of mixed heritage, the controls are from a comparatively homogeneous British group.

“The data look interesting but really need to be tested independently before I would believe the results were scientifically sound,” notes Stephen Scherer, director of the Centre for Applied Genomics at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, who was not involved in the work.

“There is much room for error, both in study design and interpretation, and too much at stake here to get this wrong,” Scherer says. Researchers involved in the study did not respond to multiple requests for interviews.

The results from any genetic test for autism are bound to be complex. IntegraGen does not market the test directly to families, for example.

A doctor must order the test and send a sample to the company’s laboratory. The company’s genetic counselors then discuss the results with the doctor or parents. “This is not a simple glucose test, and the explanation of the results is important,” Courtieu says. He declined to say how many tests the company has sold so far.

IntegraGen is supporting clinical trials to refine its SNP panel and make the test more accurate, he adds. For instance, the company is sponsoring a prospective study at the Cleveland Clinic to test 600 children, about half with autism and half with either no psychiatric diagnosis or with other conditions, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, speech delays or anxiety disorders.

“There’s a lot of work to be done to make sure that what they’ve done replicates into a larger population,” says Thomas Frazier, research director of the Center for Autism at the Cleveland Clinic and lead investigator of the clinical trial.

Any reliable test for autism would be an enormous help to clinicians, especially in cases that score on the borderline of gold standard behavioral tests, Frazier adds.

Still, for a disorder as complex as autism, genetic information is likely to contribute only one piece of the whole, Frazier says. “I don’t foresee us having a cadre of genetic tests that can do the whole trick.”

References:

1: Skafidas E. et al. Mol. Psychiatry Epub ahead of print (2012) PubMed

2: Anney R. et al. Hum. Mol. Genet. 21, 4781-4792 (2012) PubMed

Recommended reading

New tool may help untangle downstream effects of autism-linked genes

NIH neurodevelopmental assessment system now available as iPad app

Molecular changes after MECP2 loss may drive Rett syndrome traits

Explore more from The Transmitter

Who funds your basic neuroscience research? Help The Transmitter compile a list of funding sources

The future of neuroscience research at U.S. minority-serving institutions is in danger