Rising rates

A new report from the U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention finds that autism rates have risen 23 percent since 2009, from 1 in 110 children to 1 in 88.

About 1 in 88 children in the U.S. has an autism spectrum disorder (ASD), according to a new report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). That’s a 23 percent increase over rates the federal agency reported in 2009.

The data come from a nationwide network, the Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring (ADDM) Network, which tracks the number of 8-year-old children with ASDs in 14 different communities throughout the country.

According to the ADDM, prevalence increased from about 1 in 150 children in 2007 to 1 in 110 children in 2009 to 1 in 88 today. That’s a nearly 80 percent increase from 2002 to 2008. The data are based on children who were 8 years old in 2002, 2006 and 2008, respectively.

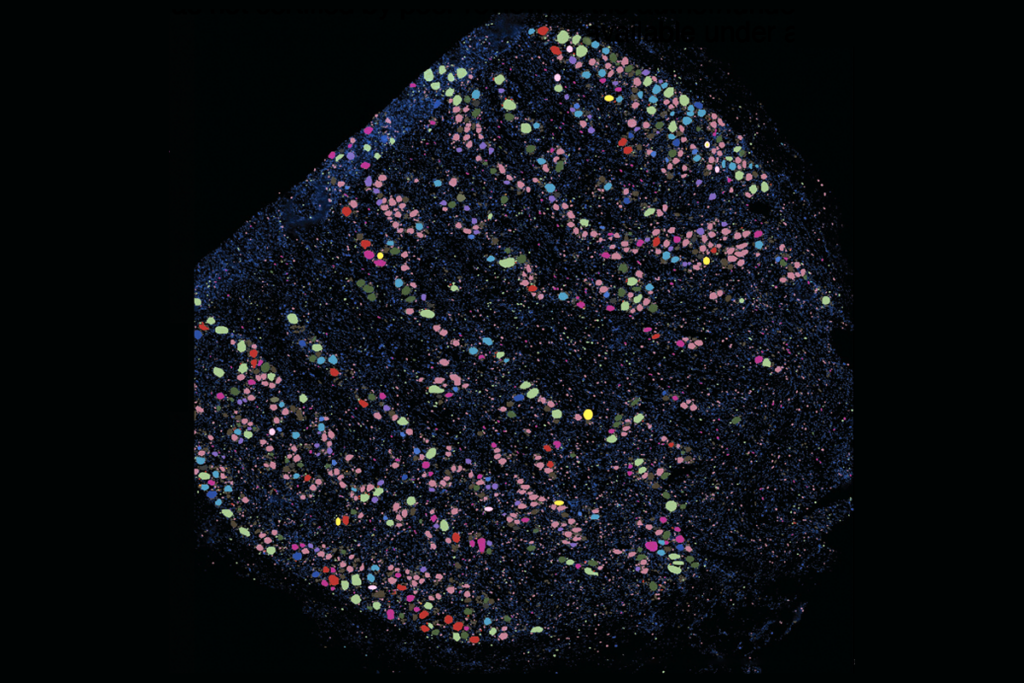

The CDC report also shows that rates vary widely across the different sites, from 1 in 47 in Utah to 1 in 210 in Alabama. New Jersey (prevalence rates shown at left), for example, has consistently higher rates than the national average. Researchers who led the New Jersey component of the study say they believe this is because of well-informed healthcare providers in the area and early identification.

However, it is still unclear how much of the increase is due to increased awareness of autism and to changes in the way the disorder is diagnosed. Though the standard diagnostic criteria have remained broadly the same since 1994, when they were published in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV), the way clinicians interpret them can change.

A study published in 2009 found that a more than 600 percent increase in autism diagnoses in California between 1987 and 2003 was due to “social and demographic changes, such as more children born to parents over 40, more active neighborhood networks, and evolving definitions of the disorder….”

Changes to the diagnostic criteria for autism accounted for about 25 percent of the increase, and younger age of diagnosis accounted for another 25 percent.

In 2010, the same research team found that children living in close proximity to a child with autism had a 40 percent greater chance of being diagnosed with autism themselves, suggesting awareness may play a major role in driving up prevalence rates.

The new analysis also finds that more children are being diagnosed at a younger age — 3 years — though most are still diagnosed after 4 years of age; Asperger syndrome typically isn’t diagnosed until 6 years of age.

The largest increases in prevalence rates occurred in Hispanic and black children, likely because of improved screening and awareness in these communities.

Though the CDC report shows increased prevalence across intellectual abilities, the greatest increase occurred in children with autism who have average intelligence. More than 60 percent of the children in the study identified as having the disorder did not have intellectual disability.

Looking ahead, changes to the diagnostic criteria — due out in 2013 when the DSM-5 is published — may again change prevalence rates, though how much is not yet clear. Some studies have suggested the changes will make it more difficult for people with normal IQ scores to get an autism diagnosis.

The new findings again highlight how important it is to figure out the factors behind the rise in autism: Whether it truly can be attributed to better awareness among doctors and families or whether there is some environmental or other factor contributing to an actual rise in the disorder are questions the autism research community must try to answer.

Recommended reading

New organoid atlas unveils four neurodevelopmental signatures

Glutamate receptors, mRNA transcripts and SYNGAP1; and more

Explore more from The Transmitter

‘Unprecedented’ dorsal root ganglion atlas captures 22 types of human sensory neurons

Not playing around: Why neuroscience needs toy models