African genetics study NeuroDev shares initial findings

The most comprehensive study of neurodevelopmental conditions in Kenya and South Africa ever conducted shares preliminary results and lessons.

In May 2019, the pouring rain in Kilifi, Kenya, was putting a damper on Patricia Kipkemoi’s data-collection plans. She had been recruiting participants for a new international autism research project called NeuroDev, and she was concerned that the seasonal weather would prevent her from collecting those participants’ genetic samples and health information by the team’s deadline two months away.

“There were a lot of cancellations and postponements by the participants due to the heavy rainfall that usually lasts till July,” says Kipkemoi, a graduate student in developmental psychology at Vrije University in the Netherlands, who is based at the KEMRI-Wellcome Trust Research Programme in Kenya and leads the Kilifi field work for NeuroDev.

The project, which launched in August 2018, was already falling short of its first-year goal: to collect and analyze data from 100 children with autism or other neurodevelopmental conditions, along with their parents.

To work around the harsh weather conditions, Kipkemoi offered to transport participants to the data-collection site and compensate them for their time. The researchers also hosted recruiting days on Saturdays for fathers, who were usually unable to get time off from work on weekdays.

The strategies worked: The team met their goal for the project’s pilot phase.

Kipkemoi and her colleagues shared these and other lessons from NeuroDev’s first year in a preprint on medRxiv in January. The researchers also reported the project’s first genetic results.

Ultimately, NeuroDev aims to collect information from more than 5,000 participants, including 1,800 children in South Africa and Kenya who have autism, developmental delays or intellectual disability, along with their parents and controls — data that stand to fill a major knowledge gap. To date, research on the genetics of neurodevelopmental conditions is primarily based on people of European ancestry, even though Africa is the world’s most genetically diverse continent.

“I am excited to see that the NeuroDev project is happening,” says Maria Chahrour, associate professor of genetics and neuroscience at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, who did not take part in this work but co-created the first cohort of African children with autism. “It’s something we needed in the field deeply to fill the genetic diversity gap.”

The lack of diversity in genetic data translates to health disparities, says study investigator Ally Kim, associate computational biologist at the Broad Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts. “We can’t just focus on Europe and U.S. all the time for these studies, because regional differences do exist.”

D

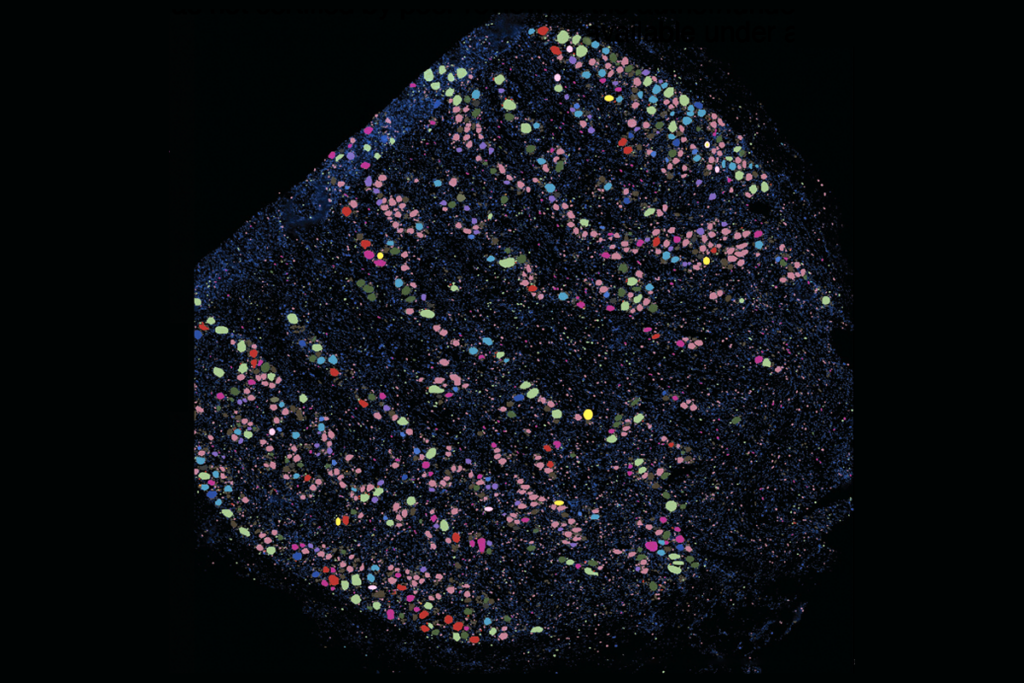

An exome analysis of the parent-child trios revealed genetic explanations for 22 of 99 children: 13 of 75 from South Africa and 9 of 24 from Kenya. (The team excluded one trio from the analysis because its samples did not pass quality control measures.) These children have genetic variants that are associated with a neurodevelopmental condition in Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) — a catalog of human genes, genetic conditions and traits.

Seven other children have what are known as variants of uncertain significance. When the researchers entered these variants into a database called MatchMaker Exchange, they discovered other reported cases of people with neurodevelopmental conditions.

This method could help researchers confirm new gene-disease relationships, says study investigator Anne O’Donnell-Luria, co-director of the Center for Mendelian Genomics at the Broad Institute. “NeuroDev study participants will contribute to that discovery.”

A drawback of the analysis, Chahrour says, is that it did not identify how frequently these variants occur in the African population. To do that, the team could leverage data from Human Heredity and Health in Africa, a project that studies how genetic and environmental factors in Africa contribute to diseases. O’Donnell-Luria says the team plans to look into this analysis for the next parts of the NeuroDev project.

The children and their parents also participated in behavioral assessments during the pilot phase to clarify how autistic people tend to present in Africa. “Collecting a lot of information on the traits of neurodevelopmental conditions and understand the patterns of behaviors in our setting is vital,” Kipkemoi says.

Behavioral assessments designed in Europe and North America may lack relevance in Africa, says lead researcher Kirsten Donald, associate professor in pediatric neurology at the University of Cape Town in South Africa.

For example, researchers in Western countries often assess a child’s level of eye contact when diagnosing autism. But in Kenya, children avoid eye contact with adults as a sign of respect, Kipkemoi says. “We are currently evaluating the cross-cultural performance of autism diagnostic and screening tools in our context, and we should be able to share more about it in our future studies.”

For now, the researchers have used the original version of the Developmental, Dimensional and Diagnostic Interview (3Di) to measure autism traits and made changes to the Molteno Adapted Scale, a developmental screening tool commonly used in South Africa for children up to 5 years of age. One of the tool’s questions asks whether a child rides a tricycle, which is uncommon in Kilifi, Kipkemoi says. “We rewrote the question that is more appropriate in our settings — for example, if the child stands on tiptoes.”

T

To do so, the researchers used the University of California, San Diego Brief Assessment of Capacity to Consent (UBACC) — translated into each participant’s language. If a participant didn’t achieve the required score, they repeated the test with additional explanation up to three times; if they still didn’t achieve the desired score, they could not enroll.

Nearly 100 percent of the South African participants consented to share their genetic information. Whereas some Americans view genetic information as private, in many African cultures people are willing to share their data when they think it may benefit others in their community, Donald says.

“That’s a very different paradigm,” she says. “You have to be able to think differently in different environments. And having the space to be able to think about those differences and bring them authentically in the project means that we are looking at high-quality data.”

The team also consulted with local communities to raise awareness about neurodevelopmental differences and to train health-care workers to combat stigma. “We find parents not knowing where to access care,” Kipkemoi says.

The NeuroDev team paused the project from March to October 2020 because of the coronavirus pandemic. During the lockdown, they could not collect new genetic samples or analyze existing ones. Once they restarted the project, they included several COVID-19 precautions: For example, they made short video explainers about the study, which the parents watch before providing consent via phone.

Even with the delay, however, the South African team has collected data from more than 2,000 participants to date and plans to wrap up by the end of June; the Kenyan team, which has collected data from more than 1,000 participants, aims to finish by the end of 2024, Kipkemoi says.

“The fact that people trusted us to do this study is a testament to the way we approached it,” Donald says. “It matters how you do the research — not just being the first people to do it.”

Corrections

A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that some of the children in the NeuroDev study have three neurodevelopmental conditions: autism, global developmental delay and intellectual disability. Diagnoses of global developmental delay and intellectual disability are mutually exclusive, and the former is given early in life, before a diagnosis of intellectual disability can be made definitively.

Recommended reading

Snoozing dragons stir up ancient evidence of sleep’s dual nature

‘Unprecedented’ dorsal root ganglion atlas captures 22 types of human sensory neurons

Explore more from The Transmitter

The Transmitter’s most-read neuroscience book excerpts of 2025

Neuroscience’s leaders, legacies and rising stars of 2025