This paper changed my life: ‘Selective erasure of a fear memory’ from the Josselyn Lab

This groundbreaking 2009 paper set a foundation for the types of memories researchers could manipulate and inspired my own approach to science.

Answers have been edited for length and clarity.

What paper changed your life?

Selective erasure of a fear memory. Han J.H., Kushner S.A., Yiu A.P., Hsiang H.L., Buch T., Waisman A., Bontempi B., Neve R.L., Frankland P.W., Josselyn S.A. Science (2009)

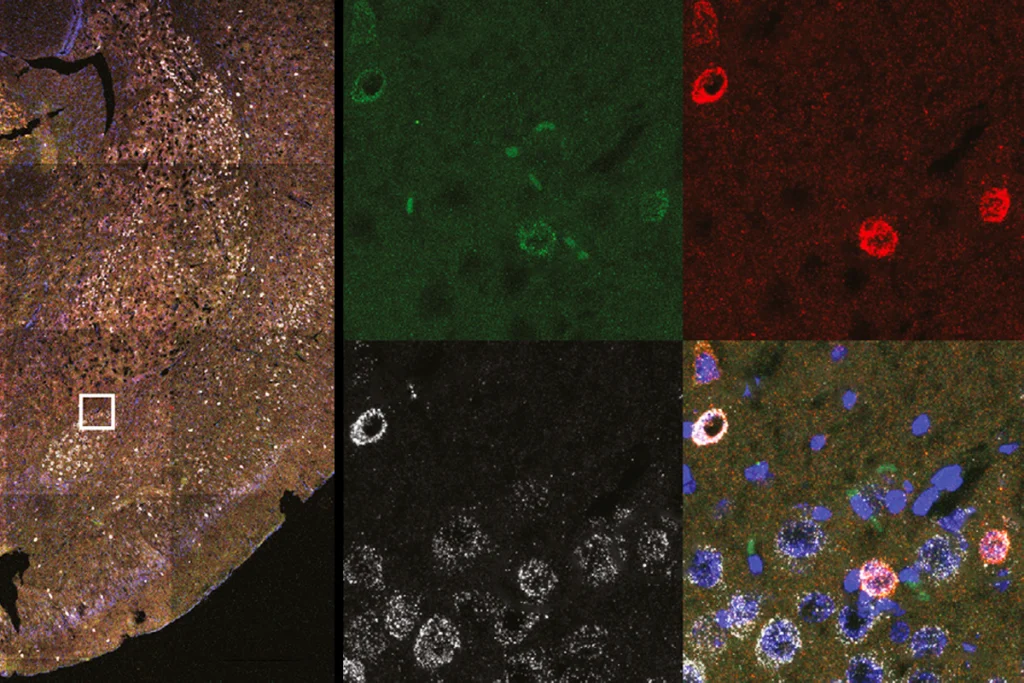

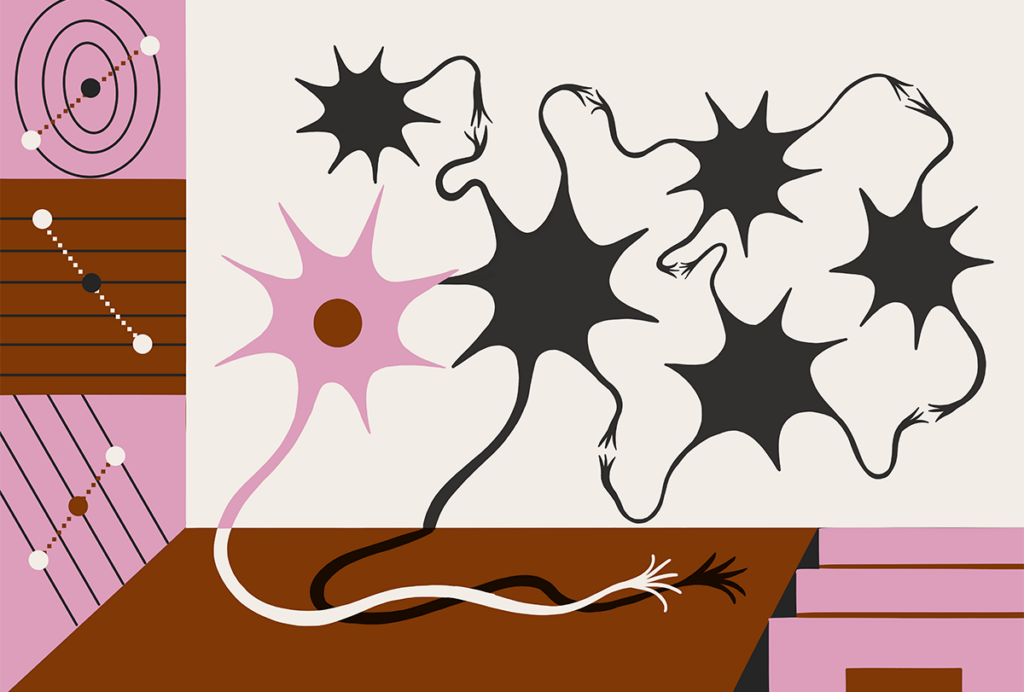

Sheena Josselyn [a contributing editor for The Transmitter] and her colleagues described how they could erase fear memories in mice by ablating a small subpopulation of cells in the amygdala. The Josselyn Lab first identified a subset of neurons in the amygdala that were active as mice learned an auditory fear-memory task. Her team then selectively deleted these cells and found that mice lost that memory. Their work revealed a fundamental aspect of memory function: that specific memories are tied to a corresponding set of neurons in the brain.

When did you first encounter this paper?

My late colleague Xu Liu and I came across Sheena’s paper in 2010, during my first month of grad school. It seemed not only exciting but also too good to be true, and relevant for what we wanted to do in Susumu Tonegawa’s lab—to attempt to activate memories.

Why is this paper meaningful to you?

There is a very wide-eyed 5-year-old scientist in me who looks at a paper title like that and realizes that it is not science fiction. Because of this paper [and its findings] in the mouse brain, we know that we can erase memories. How we scale that up to rats or monkeys or people is another story, but the ground truth is there.

On the more personal side, Sheena came by our poster at the 2011 Society for Neuroscience meeting when Xu and I presented our own work on memory manipulation for the first time. She was so thoughtful and inviting and had a very deep appreciation for what we were trying to do.

How did this research change how you think about neuroscience or challenge your previous assumptions?

When we think about memory, we think about it as this 3D web of activity that exists dynamically throughout all corners of the brain. They showed that breaking the activity of a small set of cells in a corner of the brain seemed to be enough to break the memory itself. That’s pretty remarkable, because it means that we don’t have to find the entirety of a memory in the brain.

More broadly, I think the ideal way of conducting science is to be able to take something that once felt outside the box and turn it into an experimental framework that we can use in the lab. This paper was such a beautiful demonstration of taking something that sounds super sci-fi but really grounding it in science realism.

How did it influence your career path?

Sheena’s 2009 paper directly influenced our own efforts to artificially activate memories in mice, which Xu and I published in 2012. It got us thinking, “OK, can we do the opposite of what they did?” They zigged, and we wanted to zag, but you have to know how to zig first. Their work pinpointed cells in the amygdala that were involved in the emotional components of a particular experience and showed that they could be manipulated, which influenced what we did later in the hippocampus. Because of that, I see that our work is really scientifically intertwined.

In my own lab, the paper has really influenced the kinds of experiments that we design—we try to be as outside the box as they were.

I teach this paper in my engram course every semester, and it’s one that students still tend to get very excited about. It’s probably the first paper that people sign up to present.

Is there an underappreciated aspect of this paper you think other neuroscientists should know about?

The subset of amygdala cells they delete to erase a memory is surprisingly small. I think that that’s really important—what does it tell us about how the amygdala functions and how memory works? Does a sparse representation of cells throughout the brain make a memory possible?

Another thing that I think is underappreciated is that you can erase a fear memory in the brain even in the presence of a second fear memory. If you give the animals two fear memories, but you only target and kill the cells in one of them, then only that one fear memory goes away. Meaning that if you erase one fear memory in the brain, you’re not getting rid of the capacity for the brain to feel or experience fear. There’s a very elegant amount of specificity in that paper that I think sometimes goes underappreciated.

Recommended reading

The best of ‘this paper changed my life’ in 2025

Explore more from The Transmitter

Imagining the ultimate systems neuroscience paper