Neuroscience, like much of academia, is at a tipping point with its postdoctoral researchers. Citing low pay and inadequate benefits, many postdocs have considered leaving academia in recent years, according to a 2020 Nature survey. Others are increasingly asking their institutions to make changes.

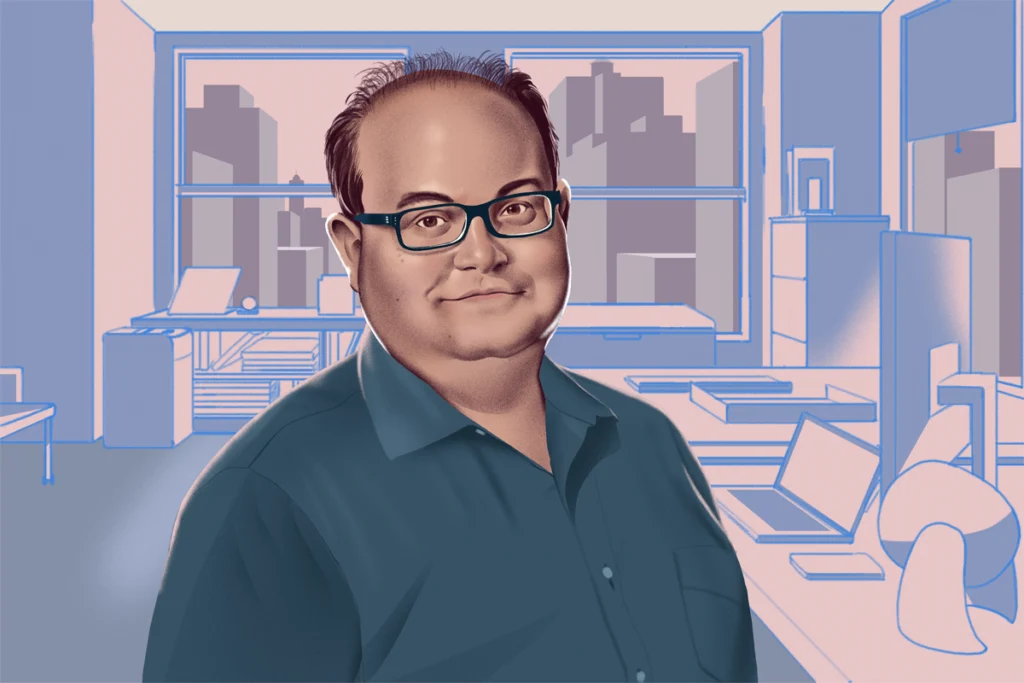

A new tentative agreement between the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai New York City and its postdoc union is the latest sign that those changes are beginning to happen. After postdocs at Mount Sinai went on strike for 12 days last month, the institution agreed to set postdoc salaries at a minimum of $72,500 per year — a 24 percent increase and more than the $70,000 recommended by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) last month. The salary boost makes Mount Sinai’s postdocs the highest paid in the nation, says Balagopal Pai, a postdoctoral researcher in pathology and neuroscience there who participated in the strike.

The move comes on the heels of other postdoc union activity across the United States: In January 2023, postdocs, graduate students and other researchers went on strike across the University of California system and successfully negotiated higher wages and increased benefits; Columbia University’s postdoc union negotiated a salary increase back in November, and Weill Cornell Medicine postdocs voted to unionize that same month, bringing the total number of U.S. institutions with postdoc unions to 10. (Postdocs at Harvard University and researchers at the NIH and New York University are also unionizing.)

Other agreed-upon changes in the new Mount Sinai postdoc contract include guaranteed parental leave and an increase in paid time off. “It’s a big step forward in the right direction,” Pai says.

The Transmitter spoke with Pai about what it was like to be involved with this process and how these changes could alter the landscape of postdoctoral positions more broadly.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

The Transmitter: How did these contract negotiations come about?

Balagopal Pai: Previously, there was no specific legal contract on paper for Mount Sinai postdocs. We were hoping to achieve a negotiation on issues such as housing, equality, childcare, discrimination and bullying, as well as compensation. And there was quite a bit of delay in Mount Sinai’s response to that proposed contract, which is why we went on strike.

We then had one very short bargaining session on 18 December. We put the offered contract out for a vote among postdocs, and 98 percent voted yes.

But the whole process has been more than two years. The unionization happened in May 2022, and then we talked with other unionized postdocs around the country and had town halls to discuss the issues we had. And then the bargaining sessions started back in October of that year.

TT: What were some of the biggest wins?

BP: In addition to the increased salary and emergency funds, international postdocs will now be able to claim a refund for what we pay to renew our J-1 visa. We usually pay a couple of hundred dollars for the visa fees, and then we have to travel to stay where there is an embassy.

We also negotiated for a relocation fund for international postdocs who join Mount Sinai. And other things, which people don’t often consider until they have to, such as policies on bullying, harassment, discrimination — those are all set in writing now.

TT: What are some of the remaining issues?

BP: I have two kids — a 5-year-old and a 7-year-old — and they were born in Germany, where I spent eight years doing my first postdoc. I have the experience of bringing up kids in another country, and I see the stark contrast here, especially in New York City, when it comes to the cost of child care. So we were asking for dedicated child-care funds for postdocs.

Another important issue is housing. We currently have access to subsidized housing for three years, and not beyond that. For me, once that three years is up, we’ll have to uproot the kids from Manhattan to somewhere else, to a different school. My wife does not have a job, and staying in Manhattan is a very tricky situation on my single salary.

Under the new contract, postdocs can claim emergency funds to help with child care and housing costs. But we still feel like it is not enough.

TT: What was the general mood surrounding the outcome of the negotiations?

BP: A full 98 percent voted positively. So that’s a big deal. We were excited. But we were also getting frustrated partway through the process. The organizing part is very difficult, because we love our research. And it was challenging for researchers to put away the work — the mice or the cells or whatever. We were working in the lab but also trying to put in our hours on the picket line. We didn’t want this to go on. So we had to call it a day and agree on this contract, because it is already a very good contract. And then we will still keep pushing for many years to come.

TT: One question people raise when talking about increasing graduate student and postdoc salaries is where the money will come from — and that principal investigators (PIs) might need to hire fewer people to afford those raises. Is that something that’s being discussed?

BP: Yes, we have that issue. Many of the PIs are saying that they might have to cut contracts short until they have new funding. Even supportive PIs tell me that they are not sure yet how they’re going to handle this. We have yet to see whether Mount Sinai will step in and contribute toward the pay — that is something that the administration and PIs will have to sort out. The NIH also put out a report that proposed $70,000 for the basic postdoc salary, so we are also hoping that the NIH eventually steps up funding toward the postdoc pay.

Important practical issues are still there. And it’s a concern for me, actually — whether I’ll be able to stay on as long as I would have liked. But overall, I’m thinking this had to be done.