From reductionism to dynamical systems: How two books influenced my thinking across 30 years of neuroscience

Nicole Rust describes her career-changing literary journey of joy, free will and the evolution of a field.

I first read Francis Crick’s “The Astonishing Hypothesis,” published in 1994, as a disenchanted undergraduate student. I knew that I wanted to change my major from chemical engineering, but I was unsure about what I wanted to switch to. In Crick’s book, I found the answer in spades. In fact, 30 years later I can still recite key lines from “The Astonishing Hypothesis” from memory: “You, your joys and your sorrows, your memories and your ambitions, your sense of personal identity and free will, are in fact no more than the behavior of a vast assembly of nerve cells and their associated molecules.” Though I wasn’t completely convinced that the hypothesis was correct, the notion that I could make a career out of studying it hit me as a profound insight. I still have my original copy of Crick’s book, complete with a dozen or so Post-it notes marking the most important passages.

I eventually ended up studying vision and memory rather than consciousness per se, but that tattered copy has continued to be influential across my career. I read it most recently a few years ago, when I was contemplating writing a book myself. Though I still very much respect the brilliance of Crick’s book, what struck me on that recent reread was how outdated it had become. I view that not as an indictment but as evidence of the evolution of our field. “The Astonishing Hypothesis” reflects an era of 1990s neuroscience in which researchers shifted toward thinking about the wonders of the brain and mind in ways that were more mechanistic and scientifically falsifiable. That approach tended to try to reduce every phenomenon to a simple explanation, such as the expression of a gene or the activity of a brain area. For instance, Crick proposed that the decisions we make may not be freely decided but instead predetermined, and that our illusion of free will may arise from what happens in the anterior cingulate cortex.

What is the modern alternative? Enter Kevin Mitchell‘s 2023 book “Free Agents: How Evolution Gave Us Free Will,” which reflects a shift toward thinking about the brain as a complex dynamical system with emergent properties that defy reduction to simple elements. In “Free Agents,” Mitchell spells out how will that is truly free could exist in a dynamical brain in which agency has evolved across millions of years. (The Transmitter published an excerpt from “Free Agents” last year.)

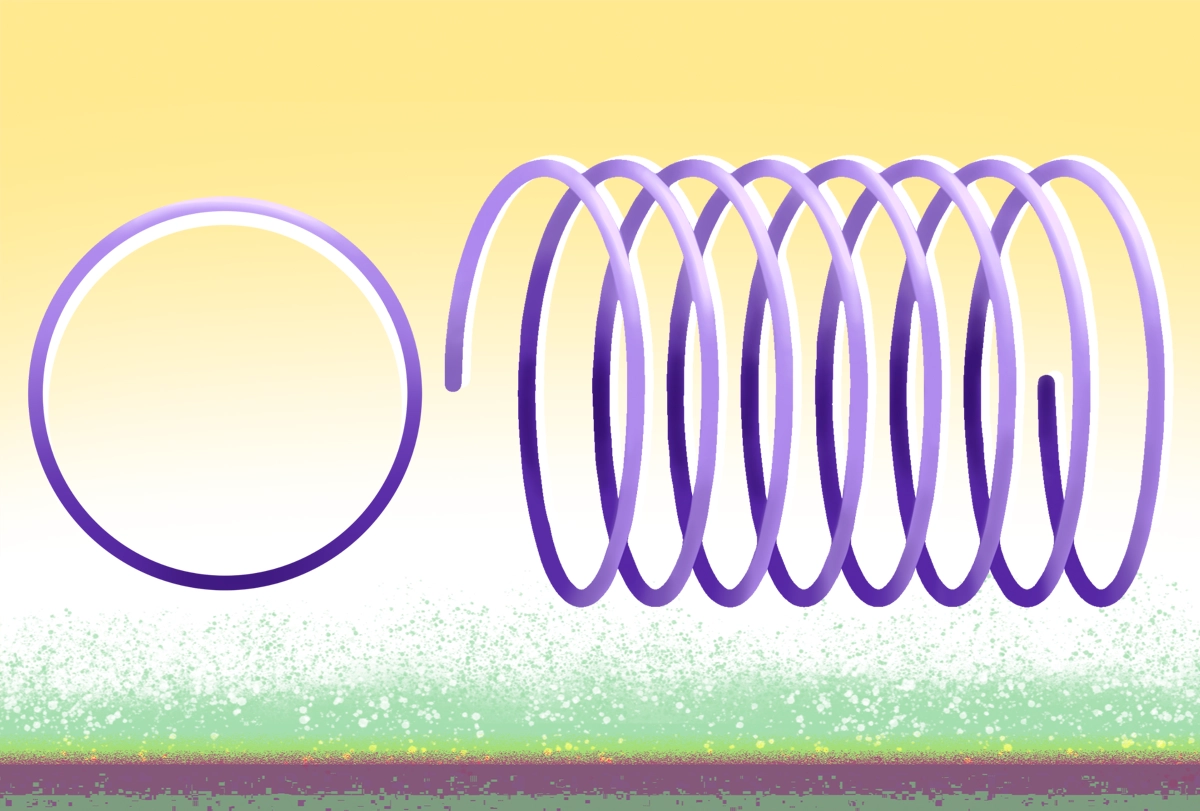

The gist of Mitchell’s proposal is that higher-level mental states do not simply emerge from the activation of neurons and their interactions, but that they also influence how brain activity will evolve in the future. In Mitchell’s account, noise allows for multiple possible future brain states, and top-down causal influences determine which one happens. It’s this process that creates free will. A long-held objection to this type of idea is that mental states cannot both emerge from brain activity and also simultaneously cause it, because in that argument, causality is “circular.” Central to Mitchell’s argument is that top-down influences do not act instantaneously but instead shape the future of the system, like a “spiral” that unfolds in time. This provocative proposal has inspired me to think about how we might test ideas about “spiraling” causality—to explain not just free will, but also functions such as seeing, remembering and feeling.

I’m very much looking forward to revisiting Mitchell’s book in 30 years to see how well it holds up. My hope is that we will have either verified that the framework is correct, or (as with Crick’s book) we will regard it as pioneering but dated, and we will have moved on to a better alternative. Either would reflect tremendous progress in our field. I can’t wait to find out.

Recommended reading

Not playing around: Why neuroscience needs toy models

AI-assisted coding: 10 simple rules to maintain scientific rigor

How basic neuroscience has paved the path to new drugs

Explore more from The Transmitter

The Transmitter’s most-read neuroscience book excerpts of 2025

Neuroscience’s leaders, legacies and rising stars of 2025