Yeast assay illuminates effects of mutations in top autism gene

Mutations in the gene PTEN that are tied to autism may be less harmful than those linked to a syndrome characterized by benign tumors.

Editor’s Note

The findings discussed in the conference report below were published 3 May 2018 in the American Journal of Human Genetics1. Updates to the original report appear below in brackets.

Mutations in the gene PTEN that are tied to autism may be less harmful than those linked to a syndrome characterized by benign tumors [and a predisposition to cancer]. Researchers presented the unpublished results today at the 2017 American Society of Human Genetics Annual Meeting in Orlando, Florida.

The findings may help to explain the diverse effects of mutations in this gene. They may also serve as a model for assessing mutations in other autism risk genes.

Researchers tied PTEN, a known cancer gene, to autism 15 years ago, when they identified a boy with both conditions. Since then, researchers have found mutations in the gene in many people with autism. PTEN is now ranked among the genes with the strongest ties to the condition.

PTEN’s main function is blocking the activation of a cell-growth pathway called PI3K. Some mutations in PTEN impair this pathway, allowing cells to grow and divide out of control. This is consistent with the observation that mutations in the gene are associated with enlarged heads in people with autism; the mutations also cause benign tumors in children [and increase their risk of cancer].

But predicting the effects of a given PTEN mutation is difficult.

“Patients present along a phenotypic spectrum, with varying degrees of neurological effects and tumor severity,” says Taylor Mighell, a graduate student in Brian O’Roak’s lab at Oregon Health and Science University who presented the new findings.

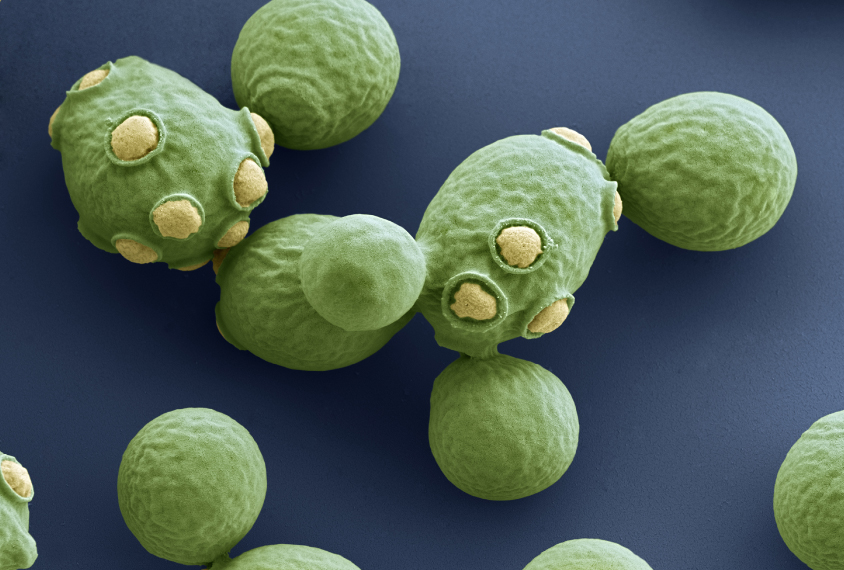

To address this problem, Mighell and his colleagues developed a way to test the effects of thousands of PTEN mutations in yeast. Yeast do not have PTEN or the PI3K pathway, so the researchers equipped them with the versions found in people. The pathway is toxic to yeast, so activating it with a sugar kills the yeast. Cells engineered with a working copy of PTEN can survive and grow because the gene blocks the pathway.

Growing pains:

The researchers created [8,012] mutations in the PTEN gene, representing 95 percent of possible [single] amino acid changes in its protein sequence. To assess the effects of each mutation, they determined how many of the yeast cells carrying each protein survive after the P13K pathway is activated. The more harmful a mutation, the more likely it is the PTEN protein is not functional, and the cells carrying it will die.

As expected, mutations known to be critical for PTEN’s ability to block PI3K severely curtail yeast survival. Mutations in another region, believed to allow PTEN to bind to cell membranes, also impair growth. These results suggest the yeast assay accurately evaluates the effects of PTEN mutations, Mighell says.

The researchers next looked at the consequences of mutations tied to various conditions, including 42 linked to autism. They found that tumor-associated mutations in PTEN tend to stunt yeast growth more than autism-linked mutations do. By contrast, mutations found in the general population have virtually no effect on growth.

The findings suggest that autism-associated variants are less damaging than tumor-associated ones, Mighell says. He and his colleagues are collecting more information about PTEN function and features in people with the mutations in order to better predict the effects of mutations.

For more reports from the 2017 American Society of Human Genetics Annual Meeting, please click here.

References:

- Mighell T.L. et al. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 102, 943-955 (2018) PubMed

Recommended reading

Too much or too little brain synchrony may underlie autism subtypes

Developmental delay patterns differ with diagnosis; and more

Split gene therapy delivers promise in mice modeling Dravet syndrome

Explore more from The Transmitter

Noninvasive technologies can map and target human brain with unprecedented precision

During decision-making, brain shows multiple distinct subtypes of activity