Women with autism hide complex struggles behind masks

A new study shows that women with autism are continually misunderstood, work to camouflage their true selves and face a high risk of sexual abuse.

Editor’s Note

We are aware that there are different views on whether ‘people with autism’ or ‘autistic people’ is the better way to refer to individuals on the spectrum. This article refers to ‘people with autism,’ in accordance with Spectrum‘s style.

Gwen is a creative, successful and intelligent young woman, making her way in the world as an artist. As a child, however, she wished to hide away and go unnoticed. From an early age, she felt different from other children, and worked hard to cover up parts of her personality by pretending to be ‘normal.’ An unhappy childhood gave way to an even harder adolescence, as she struggled to manage increasingly complex relationships with peers. (Gwen participated in our study; her name has been changed to protect her privacy.)

In her 20s, Gwen received treatment for anxiety and depression, and as she was helped to reflect on her experiences and feelings, it dawned on her that she might have autism. A psychologist validated her self-assessment with an official diagnosis, and Gwen’s life finally started to make sense to her.

She now understood why she found it so hard to get along with people at school and work, and whenever she noticed herself feeling overwhelmed in noisy, crowded shops, she realized that this was part of the sensory sensitivity that comes with autism. She now derives strength from her sense of belonging to the autism community, and is enjoying a growing sense of pride as a woman with autism.

Gwen’s story contains themes that other girls and women on the spectrum may recognize: Anxiety and alienation, the burden of trying to fit in, and challenges with social relationships. Like Gwen, many women with autism are diagnosed late in life. Others are misdiagnosed, or never come to clinical attention at all.

We sought to better understand the experiences of women with autism in hopes of finding ways to identify and help them early in life. In a study we published in July, we uncovered a signature for these women, defined by a high risk of sexual abuse, exhausting efforts at camouflage, and being continually misunderstood1. These features point to specific next steps for improving the quality of life for women with autism.

Literal language:

Most clinicians and members of the autism community agree that women with autism present differently from men with the condition. But studies that use clinical test scores and other metrics to investigate this discrepancy find few meaningful gender differences. Are the gender differences truly trivial, or are we missing them by failing to ask the right people the right questions?

To help solve this puzzle, we used an unconventional approach that involved paying careful attention to the experiences of women with autism. We interviewed 14 women with autism about their lives. We hoped that their words would give us insight into the subtle manifestations of autism in women that test scores cannot. Understanding these features should lead to better support for women on the spectrum, and help prevent them from feeling they have to hide.

Our study focused on women diagnosed with autism in adulthood. We reasoned that, compared with those diagnosed in childhood, these women’s experiences would be more likely to reveal how and why autism may be overlooked in girls. We also hoped that they could enhance our understanding of the costs of a missed diagnosis.

One of us (Robyn Steward) has autism, and her insight helped create the conditions for participants to express themselves. For example, we encouraged the interviewer to be more literal with her questions. This was especially important when we asked about sensitive topics, such as substance use and sex, where there’s a temptation to take refuge in abstract, indirect language.

Maps and prompts:

We made sure the interview room was free of sensory stimuli, such as loud noises or bright lights, that might agitate our participants. We prepared the women by sending out maps and photos of the interview room ahead of time.

If the women were still uncomfortable about an in-person conversation, we gave them the option of videoconferencing instead. And during the interview, we suggested using a timer as a visual prompt for when it was time to move from one question to the next.

Many of these adaptations would not have occurred to other members of the research team. We believe that they helped our participants open up and willingly share details of their lives. This may have led to richer data for our analyses than we would have had if the women had been nervous or reticent.

We encouraged the participants to raise topics even if we had not originally intended to discuss them. Then we used a technique for systematically coding verbal data, called framework analysis, to search these conversations for common themes.

Like Gwen, most participants had struggled emotionally in childhood and adolescence. Usually, doctors, teachers and parents mislabeled these difficulties as something else, such as anxiety, rudeness, awkwardness or depression.

Many participants felt that clinicians brushed off or ignored their concerns. Many professionals held unhelpful — and sometimes unrealistic — assumptions about autism. For example, some reportedly believed that autism hardly ever affects women.

One participant’s special education teacher told her she was “too poor at math” to have autism. Other women believed they were misunderstood because teachers and clinicians didn’t know anything about female-typical features of autism. Most said their lives would have been easier if their autism had been noticed earlier.

Social uncertainty:

Our findings suggest that teachers and clinicians need more information about how autism manifests in girls and women. They should know that even girls who have a close female friend or an interest in making friends could still have autism. And they should know that high levels of anxiety along with social difficulties in a girl is a potential sign of autism. All too often, these professionals instead misinterpret the considerable difficulties of these girls as simply ‘shyness.’

We found high rates of reported sexual abuse among our participants. This shocked the two neurotypical members of the research team, but not Steward. As an autism consultant working in education, social services and theater, Steward had heard a number of stories in which men had manipulated girls and women with autism.

The reasons for the abuse varied, but they all appeared to relate to the social difficulties of autism in the context of being female.

For instance, one woman linked an experience of sexual abuse to “not reading people to be able to tell if they’re being creepy.” Another said that her uncertainty about social rules meant that she was not sure whether she could say “no” to an abusive partner’s demands. Others felt that teenage social isolation meant they lacked opportunities to develop their ideas about staying safe through discussions with female friends.

We can’t provide a statistic on the prevalence of sexual victimization among women with autism based on our study. But our findings highlight a need for research in this area and strongly suggest that girls with autism should receive targeted sex education that includes information on consent and staying safe.

Secret identity:

Like Gwen, most of our participants are experts in pretending not to have autism — a phenomenon sometimes called ‘camouflaging.’ They said they wear a ‘mask’ or adopt a persona that is carefully constructed from copying the behavior of popular peers or fictional characters, or by studying psychology books.

Most of the women said they found the effort of passing as neurotypical to be exhausting and disorienting, and many thought it contributed to their delayed diagnosis. There are no tests for camouflaging, and this is a major barrier to clinicians and researchers understanding and helping women on the spectrum.

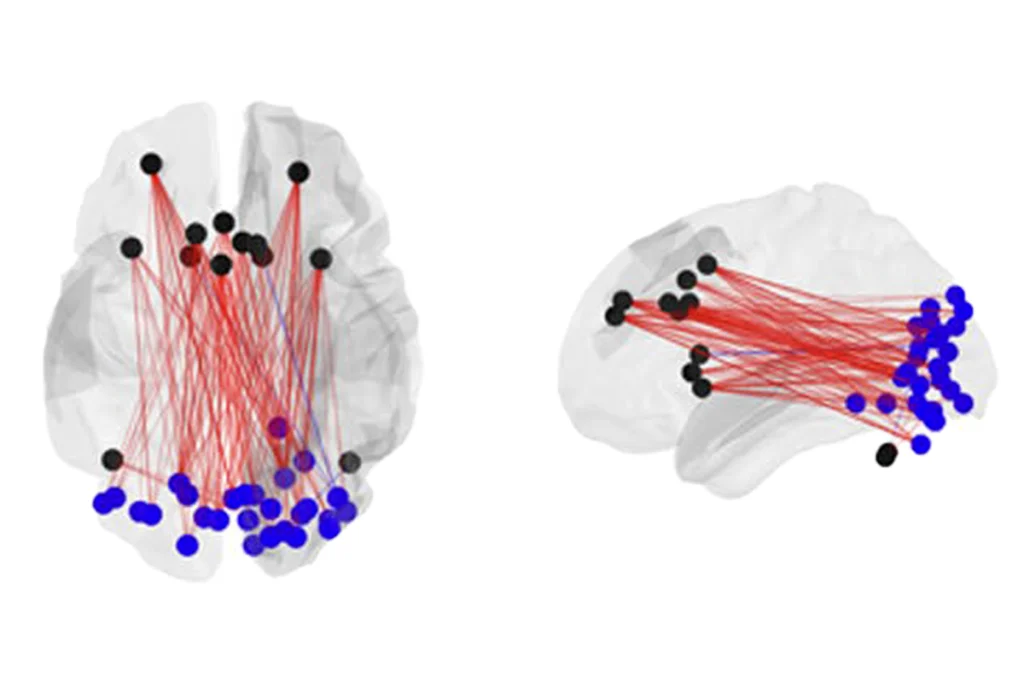

We need to develop a way to measure camouflaging so we can determine whether it is more common in women with autism than in men with the condition — as we suspect it is — and whether it has negative consequences, such as an increased risk of missed diagnosis. Such a measure could also be used clinically to improve the sensitivity of autism diagnostic assessments for girls and women.

Our findings raise wider moral questions. Until recently, many gay people felt forced to camouflage their sexuality. Thankfully, although homophobia is still rife, it is much less so than it used to be. We suggest a parallel with the obligation that many women with autism feel to pass as neurotypical.

The research and clinical establishment tends to measure progress by the number of evidence-based treatments available. In the case of autism, we propose a different metric: the extent to which societies allow people to live openly as individuals with autism, without having to pretend otherwise.

William Mandy is senior lecturer in clinical psychology at University College London. Robyn Steward is visiting research associate at the university.

References:

- Bargiela S. et al. J. Autism Dev. Disord. Epub ahead of print (2016) PubMed

Recommended reading

How pragmatism and passion drive Fred Volkmar—even after retirement

Altered translation in SYNGAP1-deficient mice; and more

CDC autism prevalence numbers warrant attention—but not in the way RFK Jr. proposes

Explore more from The Transmitter