Williams syndrome reverses patterns of neuronal branching

The branching patterns of excitatory neurons in people with Williams syndrome are roughly the opposite of the patterns seen normally, according to unpublished results from a small study presented Monday at the 2013 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in San Diego.

The branching patterns of excitatory neurons in people with Williams syndrome are roughly the opposite of the patterns seen normally, according to unpublished results from a small study presented Monday at the 2013 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in San Diego.

Neurons in Williams brains show more complex branching in areas of the cortex thought to be involved in processing emotions than in those involved in executive functions, such as working memory and problem solving. Branching in typical brains shows the reverse of this pattern.

“It seems that [the branching] is more about how the social brain circuitry may be affected — possibly enhanced to some extent for Williams syndrome, and compromised in areas that underlie aspects of cognition,” says lead investigator Katerina Semendeferi, professor of anthropology at the University of California, San Diego.

People with Williams syndrome tend to have a happy and hyperfriendly demeanor, a fascination with music, and developmental delay but strong language skills. The rare syndrome is caused by the deletion of a stretch of about 28 genes on chromosome 7, called 7q11.23, but there has been little investigation into the neuroanatomy of the disorder.

“Cells in those disorders don’t act, don’t respond or at least don’t look like typical cells.”

This is due in part to the scarcity of postmortem material, says Semendeferi, whose lab curates the world’s only collection of Williams syndrome brains, containing a grand total of 12.

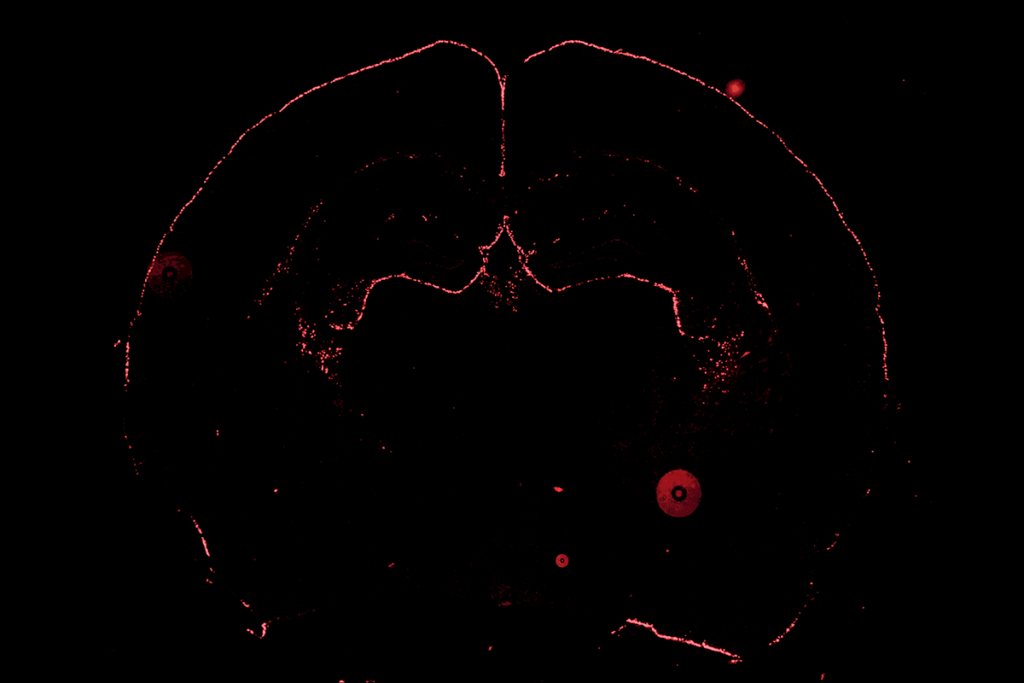

The researchers characterized and catalogued branching patterns of basal dendrites, or the lower arms of neurons, that extend from pyramidal neurons, the most common cell type in the cortex.

They focused on cells in layer III of the cortex, which connects areas between the two hemispheres, in brains from three adults with Williams syndrome. They painstakingly diagrammed individual neurons across four so-called Brodmann areas, functional divisions of the brain, and compared the patterns with those of 26 controls from previous research.

In the typical brain, Brodmann area 10, associated with inhibition in social situations and decision-making, shows more complex branching than Brodmann area 11, which is usually associated with emotion processing, says Branca Hrvoj Mihic, a postdoctoral researcher in Semedeferi’s lab who presented the work.

The Williams brains show the reverse pattern, with Brodmann area 11 showing longer and more branched dendrites.

It’s only in the past decade or so that researchers have gained a sense of how pyramidal neurons vary across the brain.

“We also know that they are compromised in some disorders, for example in autism, Rett syndrome, Down syndrome — and it turns out maybe in Williams syndrome as well,” says Hrvoj Mihic. “Cells in those disorders don’t act, don’t respond or at least don’t look typical cells. All this tells us that there is something wrong with the processing of the information at the cellular level.”

For more reports from the 2013 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting, please click here.

Recommended reading

New tool may help untangle downstream effects of autism-linked genes

NIH neurodevelopmental assessment system now available as iPad app

Molecular changes after MECP2 loss may drive Rett syndrome traits

Explore more from The Transmitter

Who funds your basic neuroscience research? Help The Transmitter compile a list of funding sources

The future of neuroscience research at U.S. minority-serving institutions is in danger