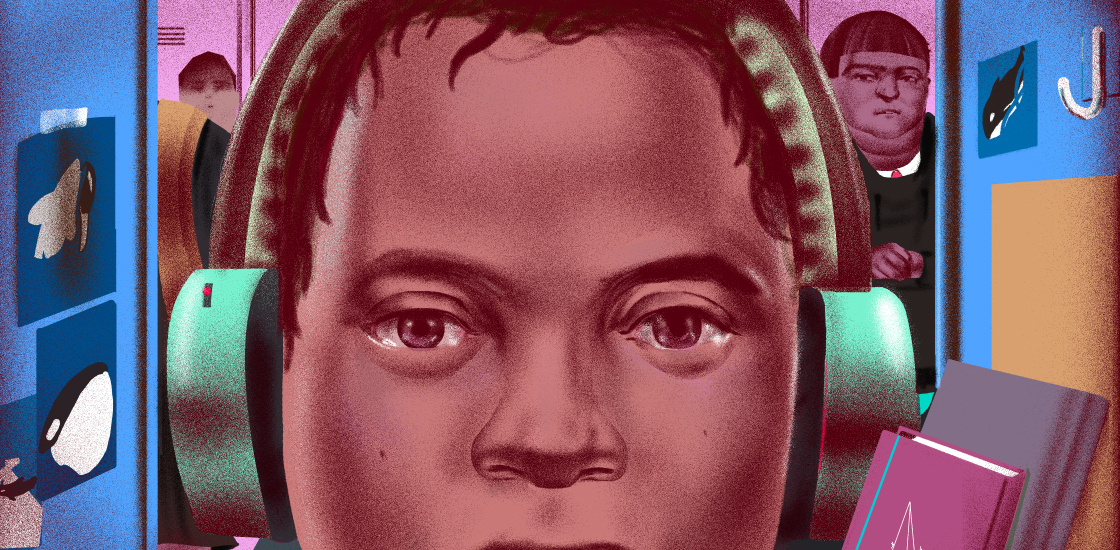

Why it is imperative to ask autistic adolescents about bullying

Being bullied puts adolescents with autism at increased risk of suicide. Identifying and preventing bullying may help prevent suicides.

Adolescents with autism are more likely than their neurotypical peers to experience bullying1. They are also more likely to have suicidal thoughts and behavior2.

We know that bullying contributes to suicidality in typically developing adolescents. When the news covers a young person’s tragic death by suicide, bullying is often mentioned. This anecdotal evidence is borne out by research: Young people who experience bullying are 1.4 to 10 times as likely to develop suicidal thoughts or behavior as their non-bullied peers are3.

Most of the time, having suicidal thoughts and behaviors goes hand in hand with having a psychiatric condition, something that is also more common among adolescents with autism than among typically developing children. But not all people who are diagnosed with a psychiatric condition experience suicidal thoughts or behavior. The higher incidence of co-occurring psychiatric conditions in adolescents with autism may reflect an underlying biological vulnerability, or the fact that they are exposed to more stressors than are their typically developing peers.

In a new study, we controlled for the presence of co-occurring psychiatric conditions and other possible confounders that could influence suicidality independently of bullying. We found that adolescents with autism who experienced bullying were still twice as likely as those who did not to later develop suicidal thoughts and behavior4.

Our findings underscore the critical importance of identifying and preventing bullying among autistic youth. Bullying must be viewed as a negative outcome for children with autism, and not accepted as something for which there is no solution.

Real risk:

We examined the clinical records of 680 autistic adolescents who had been referred to a mental health clinic in South London, England. We focused on adolescents who were not suicidal at their initial visit.

At that first assessment, 30 percent of the adolescents in our sample reported having been bullied by peers. They were nearly twice as likely as those who did not report bullying to go on to have suicidal thoughts or behaviors during the next five years.

Our findings could support a number of causal theories of suicidality. One we feel is clinically helpful is the interpersonal theory of suicide, which suggests that a combination of three factors leads to suicidal behavior: thwarted belongingness, ‘perceived burdensomeness’ and acquired capability.

Belongingness is our sense that we are accepted by others. Being married, having children and having many friends are all associated with lower rates of suicide. It is easy to understand how being bullied by one’s peers might negatively impact upon one’s sense of belonging. Being bullied can also exacerbate ‘perceived burdensomeness,’ which is the belief that others or society would be better off without you.

Young people who experience bullying may also become habituated to painful experiences and, as a result, feel less fear of death than do other young people. This sort of desensitization leads to an acquired capability for suicide, which is necessary for suicidal thoughts to be acted upon.

A call to action:

In our experience, clinicians who see autistic adolescents may regard bullying as so pervasive that it’s hardly worth commenting on.

We urge clinicians to fight this tendency and make a concerted effort to ask children with autism about bullying. And when a young autistic person reports bullying to mental health professionals, it needs to be taken seriously. Our research suggests that bullying not only contributes to suicide risk but also impacts young people’s treatment trajectories.

Most clinical services involve scheduled assessments that outline what essential information clinicians should collect during their sessions with young people. We suggest that information about bullying should be added to these assessments. Some adolescents may not feel comfortable sharing information about bullying with a professional they’ve only just met, but by asking about it early on — for example, simply asking, “Do you feel anyone is being really mean to you at the moment?” — we can make it clear that it’s something appropriate for them to talk about with their clinician. When information about bullying is difficult to collect from the young person directly, clinicians should query family members, caregivers or schools.

Teachers have a key role to play. In school settings, evidence suggests that intensive anti-bullying interventions in which teachers meet with parents are most effective5. Schools can also benefit from autism-specific anti-bullying strategies, including ‘befriending interventions,’ which help autistic children form friendships with typical peers. Schools should use robust evaluations to assess the effectiveness of such interventions and involve young people with autism in the development of their anti-bullying policies. Although moving schools should be a last resort, it is sometimes necessary. These moves should be well planned with input from the prospective school and clinician. Schools are normally keen to help early; they generally want to ensure a successful transition for new students.

For autistic adolescents remaining at their school or moving to a new one, clinicians and teachers should focus on creating interventions that enable them to develop a sense of belonging and to identify the value they bring to the people around them. In fact, these approaches can be applied to all students as a universal approach to prevent bullying. Clinicians also need to support school leaders to sustain their anti-bullying strategies; it should always be a ‘live’ issue within their local schools. In our experience, schools really value local clinicians providing advice to their school leadership, especially when advocating for regular awareness campaigns on the serious consequences bullying can have on the mental health of young people, and the need to provide targeted approaches to support those with autism.

In addition to school-based bullying, cyberbullying is an emerging concern. Further research is needed, as we suspect that young people with autism may not be equally affected by all forms of bullying. The majority of cyberbullying prevention efforts focus on educating young people, their teachers and their parents to recognize and report it.

The latest version of the Long Term Plan issued by the United Kingdom’s National Health Service calls upon mental health professionals to look beyond their consulting rooms and think about mental health efforts in communities. Bullying prevention initiatives are often left to schools or websites. Given the serious consequences bullying has on mental health, however, mental health professionals should play an active role in developing and evaluating anti-bullying initiatives.

Johnny Downs is senior clinical lecturer in the child and adolescent psychiatry department at King’s College London in the United Kingdom, and honorary consultant at the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust. Rachel Holden is a clinical psychologist at the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust.

If you or someone you know is having suicidal thoughts, help is available. Click here for a worldwide directory of resources and hotlines that you can call for support.

References:

- Mayes S.D. et al. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 7, 109-119 (2013) Abstract

- Hedley D. and M. Uljarević Curr. Dev. Disord. Rep. 5, 65-76 (2018) Abstract

- Klomek A.B. et al. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 48, 254-261 (2009) PubMed

- Holden R. et al. Autism Res. 13, 988-997 (2020) PubMed

- Ttofi M.M. and D.P. Farrington J. Aggress. Confl. Peace Res. 1, 13-24 (2009) Abstract

Recommended reading

Among brain changes studied in autism, spotlight shifts to subcortex

Home makeover helps rats better express themselves: Q&A with Raven Hickson and Peter Kind

Explore more from The Transmitter

Dispute erupts over universal cortical brain-wave claim

Waves of calcium activity dictate eye structure in flies