Why children with ‘severe autism’ are overlooked by science

Children with ‘severe autism’ are the most in need of help, yet the most overlooked in research. A new initiative is making them the primary focus.

I

t should have been a perfect day. Lauren Primmer was hosting an annual party at her home in New Hampshire for families that, like hers, have adopted children from Ethiopia. On the warm, sunny July afternoon, about 40 people gathered for a feast of hot dogs, hamburgers and homemade Ethiopian dishes. The adults sipped drinks and caught up while the children swam in the pool and played basketball. It was entirely pleasant — at least, until the cake was served. When Primmer told her 11-year-old son Asaminew that he couldn’t have a second piece, he threw a tantrum so violent it took three adults to hold him down on the grass.The Primmers adopted Asaminew from an orphanage in Ethiopia in 2008, when he was 26 months old. They had already adopted another child from the same orphanage in Ethiopia, and they have four older biological children. From the beginning, Primmer says, “He would only go to me, not anyone else.” That tendency, she later learned, may have been a symptom of reactive detachment disorder, a condition seen in some children who didn’t establish healthy emotional attachments with their caregivers as infants.

About a year and a half later, the family adopted three more Ethiopian children — siblings about Asaminew’s age — and he became aggressive. “When they first came, Asaminew was very abusive,” Primmer recalls. “He’d bite and scratch them.” The Primmers had to install gates on all of the children’s bedroom doors for their safety. Soon after he entered preschool, Asaminew began lashing out at his classmates, too. His teachers suggested that he be evaluated for autism. Doctors at the Dartmouth Hitchcock Clinic in Manchester, New Hampshire, diagnosed him with the condition. In addition to his violent episodes, they took note of his obsession with lining up toy cars and flushing toilets, his habit of taking his clothes off in public and his tendency to not follow rules at home or school. Asaminew is intellectually disabled and speaks in short, simple sentences.

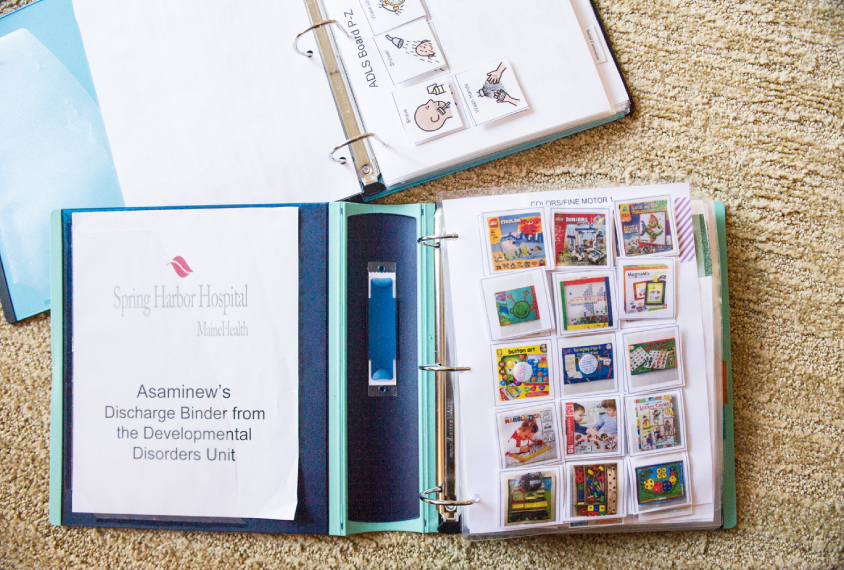

Because of his aggression, Asaminew has twice been admitted to Spring Harbor Hospital in Westbrook, Maine, about a two-hour drive from the Primmers’ home. The first time, when he was 7 years old, he spent five weeks in the acute psychiatric unit. After that stay, his relationship with those three siblings improved significantly: “They’ve become the four Musketeers,” Primmer says. But last year, Asaminew, then 10, returned to Spring Harbor for two months when he began lashing out at his parents and other adults, grabbing their hair and hitting them. Again, things got better for a while.

Then, a few months before the cake incident, Asaminew threw a three-hour tantrum. The situation escalated so much that Primmer felt compelled to call 911; the emergency medical technicians were about to sedate Asaminew when he collapsed from exhaustion. Primmer attributes Asaminew’s latest struggles in part to gastrointestinal pain. He suffers from a malfunctioning anal sphincter and, as a result, painful constipation. “Every 8 to 10 months, we have to go to the hospital so he can get a Botox injection to loosen it up so everything can move again,” she says. “I think a lot of his behavior is driven by not feeling good.”

Asaminew is also all too aware that while he is struggling with these problems, his preteen siblings are forming friendships and, increasingly, spending time with their peers outside the home. “They’re growing up, and he’s not,” Primmer says. “He can tell things are changing, and that’s becoming really difficult.” She is worried that he may, at some point, wind up at Spring Harbor for a third time.

Like Asaminew, about one-third of people with autism have a ‘severe’ form of the condition: They often have intellectual disability, little or no speech and trouble regulating their emotions. It’s not unusual for children with severe autism to become so unstable that they need to be hospitalized; 11 percent of children on the spectrum are admitted to a psychiatric hospital at least once before adulthood, mainly for aggression, self-injury or extreme tantrums, and the risk increases with age. Compared with neurotypical children, they are far more likely to require psychiatric hospitalization and are among the most challenging children for hospitals to handle.

Asaminew is lucky he lives near Spring Harbor, which has one of the few hospital units in the country that specializes in severe autism. Under the direction of child psychiatrist Matthew Siegel, a multidisciplinary team of psychiatrists and therapists there works to identify what pushes children into crisis, to stabilize them and to get them back home and into school. The unit accepts any children, aged 4 to 20, with intellectual disability who might pose a risk to themselves or others, but most of those admitted have autism; the typical stay is about 40 days.

Five years ago, Siegel’s group joined forces with the five largest child psychiatry units across the United States — each of which has about a dozen beds — to form the Autism and Developmental Disorders Inpatient Research Collaborative. Together, the collaborative treats around 1,000 children each year. “I realized that we have this enormous opportunity to study this population,” Siegel says. “It’s a controlled environment, lots of kids migrate through these units, and a high proportion are more severely affected.”

The collaborative’s researchers are trying to characterize aggression and self-injury in children with severe autism. They are tracking the children’s medications and physiological changes using wearable devices. And they are also crafting a more nuanced portrait of ‘severity’ — one that takes into account how trauma, depression, anxiety and other factors affect a child’s behavior, communication and coping skills. At the moment, there’s no consensus on how to define severity: Is a child with every textbook trait associated with autism, plus intellectual disability, more or less severely affected than one who has an average intelligence quotient but bites himself and others?

The goal, Siegel says, isn’t just to guide care in the six hospital units. “The ultimate value of this work will be putting it out there so anyone, from general psychiatric hospitals to caregivers, can offer better care to these severely affected kids.” This information is urgently needed. According to one 2014 survey, most child psychiatry residents have little experience with autism, seeing fewer than 15 children with the condition per year during their two-year training. And when doctors turn to the literature, there’s scant advice to guide them, because few autism studies have included people at the severe end of the spectrum. When it comes to characterizing severe autism, Siegel says, “We have a long, long way to go.”

Off the radar:

A

utism has long been recognized as a spectrum disorder, with its behavioral features ranging from mildly disruptive to downright dangerous. Yet traditional studies have largely ignored severely affected children — perhaps because they are unpredictable. These children can have uncontrollable tantrums or attack investigators, and many of them find it difficult, if not impossible, to sit through hours of tests. Some have sensory sensitivities that make lying still in a loud, enclosed brain-imaging machine tortuous. Those who are nonverbal or minimally verbal typically cannot answer even simple questions.“Studying this population is just very, very hard,” says Logan Wink, head of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, which is part of the collaborative. “These kids are not cooperative, and they are even dangerous at times. And families are stretched so thin as it is, it’s hard to add research on top of that.”

Starting in 2014, Siegel set out to summarize the extent to which children with severe autism are represented in the past two decades of research. That task proved far more complicated than he had anticipated. Not only did the definitions of ‘severe’ vary, but there was little consistency in the intelligence tests and language assessments studies used, making meaningful comparisons difficult. “The overall point,” he says, “is that these children are not being well described or included in research studies.”

That lack of inclusion has translated to little effort to develop treatments for this population, and little awareness, even within the medical community, of the treatments that do exist. There are only a dozen specialized child and adolescent psychiatric units across the U.S. (Only one, the 14-bed unit at the Sheppard Pratt Health System in Baltimore, Maryland — which is part of the collaborative — is in a city with more than 500,000 residents.) The majority are designed to treat mood disorders or psychosis, which means they are best suited for young people who can identify and talk about their feelings.

Depending on where they live, children with severe autism are sometimes admitted to general psychiatric wards, alongside mentally ill adults. “When our kids land in one of these,” Wink says, “the unit often has limited awareness of what to treat or how to do it.” She got a call earlier this year from a bewildered resident at one such facility, who was looking after a young adult in Wink’s care. “[The resident] told me, ‘He’s sitting in the quiet room, rocking and making animal noises.’” The resident, she says, “couldn’t even fathom that. You can go all the way through training and never see these very severe cases.”

Aside from stabilizing a child medically, general psychiatric wards offer no benefit, says Catherine Lord, who runs the Center for Autism and the Developing Brain at New York-Presbyterian Hospital in White Plains, New York. When the children she works with are admitted to the clinic there, it’s only out of concern that they’ll seriously injure themselves or someone else, she says. “We do everything possible to keep kids out of there.”

Instead, some institutions in the collaborative have created a “step-down program,” which develops treatment strategies for the children while they are in the hospital, and also for when they get out. The psychologists, psychiatrists, social workers, occupational therapists, speech therapists and teachers coordinate their plans, tailoring the use of medications and behavioral programs to each child. The staff encourage parents, aides and teachers to shadow them, learn the techniques they employ and continue them at home and at school.

Even with all this expertise and effort, the work is slow-going. “You have to be satisfied with small moves of the needle,” Siegel says. “If we see a 30 percent reduction in self-injurious behavior, we’re really happy.”

”“Studying this population is just very, very hard.” Logan Wink

In crisis:

E

arlier this year, the collaborative’s six units set out to quantify the factors that contribute most to children ending up in their care. The researchers compared 218 children admitted to one of their inpatient programs and 255 children with autism who’d never been hospitalized, but who were registered as outpatients in the Rhode Island Consortium for Autism Research and Treatment. Having a mood disorder, the researchers found, is the single strongest predictor of psychiatric hospitalization, followed by sleep problems. Other risks include serious impairment in social communication and adaptive functioning (everyday skills such as tying shoes or brushing teeth) and living in a single-parent home. By screening for these factors, doctors and families may be able to stave off behavioral crises before they lead to hospitalization, says clinical psychologist and lead researcher Giulia Righi.Two more studies, published in June, noted additional risks. In one study, the collaborative reported that trauma from physical, sexual or emotional abuse can lead to extreme irritability and anxiety in children with autism. And, as with typical children, children with autism who have mood or anxiety disorders are more prone to suicidal thoughts than those who do not have these other conditions.

This kind of detailed profiling has already reversed one long-held assumption. In yet another study from June, the collaborative reported that children with low verbal ability are not, as routinely expected, more likely to exhibit problem behaviors, such as harming themselves or others, than verbal children on the spectrum. The researchers compared 169 minimally verbal and 177 verbal children. In both groups, they found, it is the ability to adapt, or having effective coping mechanisms, that lowers the likelihood of dangerous behaviors — and, as a result, hospitalization. “Communication can be one way to cope with distress, but it’s not the only way,” says Carla Mazefsky, a psychologist at the University of Pittsburgh, which hosts a collaborative site.

Teaching children with autism coping and communication skills is an important part of what goes on at Spring Harbor. The small, 12-bed hospital unit has an educational program called Spring Harbor Academy, in which each child receives one-on-one instruction during school hours. The children also go on regular outings to the grocery store, the swimming pool or other sites in the community. The environment the teachers try to create for the children is vastly different from the one in a public school, says Janene Dorr, who has taught at the academy for nearly a decade.

Once a child is admitted to Spring Harbor, Siegel’s team starts with a comprehensive assessment. Does the child have an undetected tooth abscess or undiagnosed mood disorder, such as depression or anxiety? Is there stress at home — divorce, abuse or perhaps an eviction notice because the child screams uncontrollably? Does the child struggle to communicate or have sensory sensitivities? “It’s not usually one thing,” Siegel says. “It’s usually a combination of factors that trigger the behavioral issues that get them into our inpatient program.”

Every Monday and Thursday at 8 a.m., Siegel and other staff at Spring Harbor gather around a conference table to discuss the children in their care. To the uninitiated, the barrage of information is dizzying — and heartbreaking.

One Thursday in early May, 11 staff members focus on a graph projected on the wall. The graph charts the frequency of aggressive episodes of a 10-year-old who was admitted two weeks ago, when he’d transformed from a seemingly happy boy to an obviously agitated one. The line on the graph jumps up sharply at first, reflecting peaks in aggression — when he hit others, smacked his head against the floor or tore off his clothes — and then slopes down as he has become stabilized.

This boy is a picky eater who subsists on a specific brand of chicken nugget at home, but the previous night at the hospital, he ate crinkle-cut fries for the first time, his occupational therapist says. His mother closely watched how the staff encouraged him to eat, taking mental notes for later. The social worker says she is pleased that the boy’s interactions with his parents have become less fraught during their visits. Siegel notes that he’s taken the child off one psychotropic medication but may replace it if any signs of depression reappear. One of the boy’s teachers in the educational unit says he is communicating well, both verbally and with a device; and increasingly, he is using a new coping mechanism — pacing in the hallway — to calm himself when he gets frustrated, rather than lashing out.

The staff go on to discuss several more children. In each instance, the graph charting episodes of aggression or self-injurious behavior trends downward during hospitalization. One teenage boy whose father is being investigated by child protective services for exposing him to pornography, is “not touching others, but he’s exposing himself,” one psychiatrist says. Another boy has stopped pinching other students, a teacher says. But he did slap his own face, albeit not hard, for two hours the previous day. A psychiatrist says the new gastrointestinal medication the boy is taking seems to be working, and he is sleeping better.

After the meeting, Siegel heads upstairs to a classroom, which, like any other, is decorated with colorful, information-packed posters. The pupils are all absorbed in tasks on computers, tablets or worksheets — except for one boy. The 11-year-old boy, slight with light hair and freckles, is nonverbal, and so he doesn’t explain why he’s pacing and trying to push his way into an adjoining classroom. The teachers and aides wear protective padding on their arms but keep their hands off him anyway. They speak to him softly, walking up and down the hallway with him until he calms down. At many facilities, says Siegel, the staff would simply have restrained the boy.

Siegel approaches a girl working on a tablet and says hello. “Say hello to Dr. Siegel,” the teacher tells her. After a long pause she complies, glancing somewhere in the area of his shoulder. Her forehead is swollen and she has two black eyes. In the hallway outside the classroom, Siegel explains that the child, who is 13 years old, sometimes sleeps only a few hours each night; when that happens, she cries uncontrollably and slams her head against walls, tables, whatever is nearby — hence her injuries, and the helmet on the nearby table. Siegel suspects she has a mild form of bipolar disorder along with her autism. In addition to exercises to boost her communication and coping skills, he has started giving her a low dose of a mood stabilizer.

“We won’t know for several days if it’s effective,” Siegel says. (Siegel later told Spectrum that the medication did indeed help.) According to the girl’s medical history, this is the first time anyone has investigated whether some of her behaviors might stem from something other than autism.

”“If we see a 30 percent reduction in self-injurious behavior, we’re really happy.” Matthew Siegel

A challenging mix:

M

any children with autism have other conditions, including mood disorders, anxiety and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Studies show that up to 50 percent of individuals with autism manifest ADHD symptoms, for example. But little is known about the extent of the overlap between severe autism, in particular, and these other conditions.The collaborative is trying to pin it down. As part of that effort, the researchers have tracked prescription drug use in the children admitted to their units. In May, they reported that of 350 children in their collective care, 90 percent were taking psychotropic medications when they were admitted. “It’s a huge number, but it’s not surprising, given that these kids are in such distress that they’re being hospitalized,” Wink says.

Surprisingly, that proportion jumped up to 97 percent when the children were discharged: More children were taking more meds — mostly antipsychotics, stimulants for ADHD and sleep aids — when they left the hospital than when they came in. Wink says she expected a decrease, given the units’ emphasis on behavioral treatment, but the spike may reflect newly diagnosed conditions among the hospitalized children. The study revealed another surprise: Two months after discharge, the children’s psychotropic drug use dropped to 64 percent. Perhaps the children’s features lessen as they transition back to their homes, Wink says, or perhaps the drugs’ side effects spur family doctors to stop the children from taking them. Researchers at the collaborative plan to study the reasons for this drop in medication use.

The collaborative’s initiative to explore the genetic architecture of severe autism may yield additional clues. The researchers intend to recruit 1,600 children with autism and their families to provide DNA for sequencing analysis. Members of nearly 700 families have provided blood or saliva samples so far. Of the children with autism in those families, nearly half have significant intellectual disability, and one-third are minimally verbal. “Most sequencing has been done on kids that are more high-functioning,” meaning those children who need minimal support, says Susan Santangelo, director of the Center for Psychiatric Research at the Maine Medical Center Research Institute. “We’re interested in how children with severe autism differ, and potentially identifying subsets of children with severe autism with common physical, psychiatric and behavioral traits.” This kind of subtyping, she says, could pave the way for specialized treatments.

The collaborative is also turning to technology: The researchers hope to develop a small, wearable monitor to predict aggressive or violent episodes. When Siegel asks Asaminew how he’s feeling during an outpatient session in May, the boy replies, “I’ve been sad and happy and mad.” The same is true for most children severely affected with autism. “They can’t say, ‘I’m tired’ or, ‘This math is too hard,’” Siegel says. Even the most observant caregiver may be completely unaware that a child is building toward a tantrum. But these outbursts are not “out of the blue,” Siegel says. “It’s just that we can’t read it.”

Last year, the researchers launched a pilot project using a device called an E4 wristband that tracks physiological arousal, as measured by sweat. The instrument, which is roughly the size of an Apple Watch and costs about $1,500, has no display, but ultimately the researchers hope to devise a user-friendly version, such as the wearable fitness tracker FitBit, that would indicate low-, medium- and high-risk states for aggression or an emotional meltdown. It would flash from green to yellow to red to alert caregivers when it’s time to intervene. Devices of this sort might also help children recognize their own internal state and deploy strategies for calming themselves or communicating their distress in time for someone to help them. “That’s the holy grail,” Siegel says.

To map children’s physiological states to their emotions and behavior, the researchers are recording data in two settings. They’ve outfitted 22 children at the sites in Maine and Pittsburgh with a portable E4 Wristband; as these children go about their routines in the units, a technician follows in lockstep, coding physiological changes to the children’s fluctuating emotions and behaviors. The researchers have assessed another 55 children wearing a different physiological sensor while those children perform structured assessments. These assessments involve tasks that range from enjoyable (playing with bubbles) to frustrating (building a tower with an examiner who takes increasingly longer to add her blocks, and sometimes removes one instead of adding it). These sessions are recorded on video, and researchers code the reactions later.

The setup might sound straightforward, but it is in fact extremely challenging to decode a child’s behavior, Mazefsky says. “If a kid is flapping their arms or flicking their fingers in front of their face, it might be because they love something and are really excited, or it might be because they’re getting really agitated and distressed.” Facial expressions don’t necessarily match other emotional cues, either: A child might be smiling while emitting a disturbing high-pitched whine. “All those layers make it really complicated to say, ‘This child has had a minus 3 for emotion, which is the same thing as this other kid’s minus 3 emotion, which looks totally different,” Mazefsky says. “It took us almost nine months to get reliable results on our coding scheme.”

The preliminary data from the wearable monitors are encouraging, but even if the devices prove viable, they are years away from clinical use. An analysis of readings from the 22 children suggests that the method predicts the onset of aggression up to one minute in advance. “It might not sound like a lot, but a minute is a huge amount of time just to ensure the safety of those around and of the individual, and to employ some of the strategies we already know about for handling agitation and the escalation,” Mazefsky says.

A minute’s warning would make a huge difference in the Primmer household. Lauren Primmer is doing everything she can to keep her “love bug” at home and in school. She brings Asaminew to see Siegel every four to six months, and she applies all the lessons she has learned from Asaminew’s stays at the hospital, such as saying “eyes” to get his attention if he’s not looking at her, using visual schedules he understands and telling him to “take space” and calm down away from others at the first sign of unsafe behavior. As committed as she is to Asaminew’s care, his unpredictable outbursts are exhausting and disruptive and make it difficult to devote time to care for her other five children at home. The aides she’s hired to work with Asaminew at home help, but ‘perfect days’ with no threat of an episode feel a long way off. For now, she and Asaminew keep working on good days, one at a time.

Corrections

This article has been modified from the original. Asaminew Primmer is 11 years old, not 12.

Syndication

This article was republished in The Independent.

Recommended reading

Too much or too little brain synchrony may underlie autism subtypes

Developmental delay patterns differ with diagnosis; and more

Split gene therapy delivers promise in mice modeling Dravet syndrome

Explore more from The Transmitter

During decision-making, brain shows multiple distinct subtypes of activity

Basic pain research ‘is not working’: Q&A with Steven Prescott and Stéphanie Ratté