Catrina Thompson doesn’t worry about the safety of her 16-year-old autistic son Christopher when they’re in their hometown of Winston-Salem, North Carolina. There, Thompson is chief of police, and most people on the force know Christopher, she says. The officers also all get two training sessions on how to interact with autistic people.

But when Thompson and Christopher visit family out of state, she says, the fear creeps in. “When I go to Michigan, I’m not Chief Thompson,” she says. “I’m Catrina, and Christopher is not the chief’s son, he’s Christopher. In some people’s mind, he just looks like a big Black kid. And that, when coupled with his behaviors, can be intimidating or even scary to an officer who hasn’t been trained.”

As a police officer and parent, Thompson knows all too well how badly interactions between autistic people and law enforcement can go. From beatings and violent arrests to deadly shootings, police use of force against autistic people is not uncommon.

In 2015, for example, New York Police Department officers beat and injured Troy Canales, a Black autistic teen who was sitting outside his home, according to a lawsuit. In 2017, Lindsey Beshai Torres called for an ambulance when her autistic son was having a meltdown; instead, two Worcester, Massachusetts, officers arrived and knelt on the 10-year-old’s body as they handcuffed him, another lawsuit alleges. In 2018, a school resource officer in Statesville, North Carolina, handcuffed, restrained and taunted a 7-year-old autistic boy who was agitated after switching to a new medication. And in 2019, police in Brooklyn Center, Minnesota, shot and killed Kobe Heisler, an autistic 21-year-old.

As violent encounters between police and autistic people continue to make headlines, many states and police departments have added training on how to interact with people on the spectrum to their police-education roster. Better training, some say, offers one solution to the ongoing problem of police force being used against autistic people, particularly autistic people of color.

“As a Black person, as an autistic person, these issues are pretty intimate to me,” says Finn Gardiner, an autistic self-advocate and communications specialist at the Lurie Institute for Disability Policy at Brandeis University in Waltham, Massachusetts. “I’m pretty scared when I’m walking down the street and see a bunch of police officers.”

But what constitutes effective training is difficult to establish. There is scant research on how well various kinds of training programs work, and poor trainings can do more harm than good, experts say. Some research suggests that training makes officers more confident that they understand autism, but no less likely to use force.

Compounding the problem is the fact that few police departments track officers’ behavior to see whether autism education makes a difference. Spectrum surveyed dozens of large police departments across the United States. Of the 20 departments that responded, 18 reported that they offer autism training, but only 2 of these had collected data suggesting that violent encounters decreased after training. “There is no method of tracking the effectiveness of the annual training,” a spokesperson from the Jacksonville, Florida, sheriff’s office told Spectrum in response to the survey questions.

A consensus is emerging that police training on autism should be standardized across departments, involve autistic people and their families, and include regular refresher sessions. But some experts and advocates say the best way to decrease violence may be to minimize interactions between police and autistic people altogether.

“Nobody wants a person with autism to have a negative interaction with law enforcement — not law enforcement, not families, not anyone,” says Neelkamal Soares, professor of pediatric and adolescent medicine at Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo. “So let’s find a constructive way to reduce the frequency.”

Training troubles:

Many police departments offer autism training, but the sessions are often optional and vary wildly in length, format and quality.

For example, recruits at the Riverside County Sheriff’s Department in California are required to complete 15 hours of autism training, plus an additional 4 hours once they’re hired. But elsewhere, autism training might be boiled down to a 13-minute video or slideshow. In some places, autism experts run the training; in others it falls to a local parent or officer with no credentials.

“Training is all over the place,” says Allen Copenhaver, assistant professor of criminal justice at Lindsey Wilson College in Columbia, Kentucky. “From nonexistent to proficient.”

Cash-strapped police departments tend to lump it in with mental-illness training to save money and time, Copenhaver says. When the Lexington, Kentucky, police department first brought on Abigail Love, director of Police Community Autism Training, the chief gave her just 15 minutes with the officers, Love says. “We said, ‘Okay, we’ll take it,’ and we did the firehose method.”

But even longer trainings can fall short if they exclude autistic people or focus exclusively on nonverbal or intellectually disabled people with the condition. This ‘catastrophic’ view of autism confuses officers, experts and advocates say, and potentially does more harm than good. “Are they learning anything about the strengths of autism? Or is it simply deficits?” says Morénike Giwa Onaiwu, an autistic self-advocate and humanities scholar at the Center for the Study of Women, Gender and Sexuality at Rice University in Houston, Texas. “Because if so, then the training could take someone who is mostly a blank slate and feed stigmatizing information into that person.”

Onaiwu says that as a Black woman, she is used to being stopped by the police, but one incident stands out: When an officer approached her car one day, she began thinking about her father, who was once beaten so badly by the police that he had to go to the hospital. Though nervous, she tried to make eye contact with the officer — a challenge for many autistic people — but may have stared too intently, she says, unnerving him.

When Onaiwu tried to answer the officer’s questions, he mistook her tendency to repeat him — a common autism trait called echolalia — for mockery. And matters only got worse when he spotted a metallic ‘stim’ toy, which Onaiwu carries around with her everywhere. Some autistic people use these toys to help ease anxiety or repetitive behaviors. The officer immediately became stern and ordered Onaiwu to get out of the car — while her young daughter, who is also autistic, watched from the back seat. “It was frightening,” Onaiwu says. “It could have ended so differently.”

After that episode, Onaiwu has kept her now-teenage children from driving. “I’m too nervous,” she says. “It’s unfair to them. But they’re alive.”

Another problem with police training is that many sessions are one-offs, giving officers too little time to absorb information about autism. Without any continuing education, even the best training program won’t make police encounters safer for autistic people, says Lauren Gardner, administrative director of the Autism Program at Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital in St. Petersburg, Florida. “You cannot just get rid of these knee-jerk assumptions in these one-and-done trainings. People don’t learn things from a one-off session.”

Police departments and trainers say they get positive feedback from officers, and anecdotes abound of police officers finding missing autistic children or loading their squad cars with gear autistic people might need. But many don’t formally assess the impact of their autism training.

Of the 18 police departments that told Spectrum they provide autism training, just 7 reported any change in outcomes since their autism training began — and 5 of these offered only anecdotal reports. Only six had tested officers on their mastery of the material presented; the rest relied on reviews from officers or nothing at all.

Actual research on the effectiveness of police autism training is rare, and the findings are mixed. Compared with officers who receive no training, those who watch a short video score higher on an assessment of their autism knowledge and confidence in identifying and interacting with autistic people, according to one 2012 study. But officers who say they feel more confident after training may not know more about autism than untrained officers, according to a 2020 study. In that analysis, officers with prior training were just as likely as untrained officers to use physical force or handcuffs on an autistic person, or to admit one involuntarily to a hospital. They performed better on a test of autism knowledge after a new training designed by the study authors.

“By and large, these programs have a very little amount of data about their effectiveness,” Soares says. “There aren’t good studies that compare the officers that have received [training] to the ones who haven’t in a randomized or in a blinded fashion.”

Research restrictions:

Part of the reason this research is so scarce is that it’s difficult to design. To truly determine a training’s effectiveness, researchers say, studies would have to follow officers after training or collect data on how the officers’ behavior changed — access that police departments are often unwilling to grant. Many police departments don’t even collect that information: Only three of the departments Spectrum surveyed tracked encounters between police and autistic people in a usable way. (Another four said that a disclosed autism diagnosis might be included in incident reports.)

“We don’t have the ability to collect data,” Gardner says. “We can’t track the number of individuals being arrested or involuntarily hospitalized by the officers we trained. It’s hard to know the real-life impact it’s having.”

Even when researchers do get access, the sample sizes are often small, and they typically rely on pre- and post-training tests or officer self-reports, which can be impacted by bias, says Kathryn White, assistant professor of pediatric and adolescent medicine at Western Michigan University. Because many training sessions are voluntary, they are not randomly assigned: Officers who sign up for autism trainings tend to have a personal connection to the condition, which can skew the results, researchers say.

Some researchers are working to develop better measures. Love and her colleagues designed a 13-item scale to assess officers’ autism self-efficacy, or their belief in their ability to interact safely with autistic people. The officers’ scores are linked to their actual autism knowledge, the researchers found, suggesting that the scale could be used to measure a training’s effectiveness.

A criminal-justice survey to be distributed to autistic people, caregivers and law enforcement professionals in 18 participating nations lies at the center of another assessment effort, led by Lindsay Shea, director of the Policy and Analytics Center at the A.J. Drexel Autism Institute in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The survey includes questions on race, Shea says, which may shed some light on how race intersects with autism and criminal justice. The International Society for Autism Research plans to release the results in 2021, with a policy brief to follow in 2022.

But ultimately, researchers will need police department resources and buy-in to conduct longitudinal research. “It can be very difficult,” says Laurie Drapela, associate professor of criminal justice at Washington State University Vancouver in Washington. “That doesn’t mean it’s not worth doing. It’s a lot of money, a lot of time and you have to have your research design set before the trainer ever walks in the room.”

In the meantime, advocates and researchers have developed a set of recommendations for police departments. First and foremost, training should be mandatory for all police officers — a step that a handful of states, including Florida, have already taken. It should begin in the academy, with periodic refresher courses for officers on the job. The curriculum should be consistent across police departments, both to save resources and to ensure that autistic people are safe wherever they go. And that curriculum should be tailored to the needs of police officers, with a special focus on de-escalation. Training also works better when it includes local people with autism and their families, according to a 2018 report.

“Officers say that they’re not here to diagnose and they don’t want to be told how to diagnose,” Love says. “What we need to do is say, ‘Here’s some characteristics that you should watch out for, and here’s how you can respond.’”

That kind of advice informs the Cops Autism Response Education (CARE) project, a training program created by St. Paul Police Department officer Rob Zink and the Autism Society of Minnesota. At Zink’s insistence, his co-teachers at the Autism Society went through a citizens’ police academy course to help them better understand the challenges officers face in the field, he says. “It radically changed their perspective.”

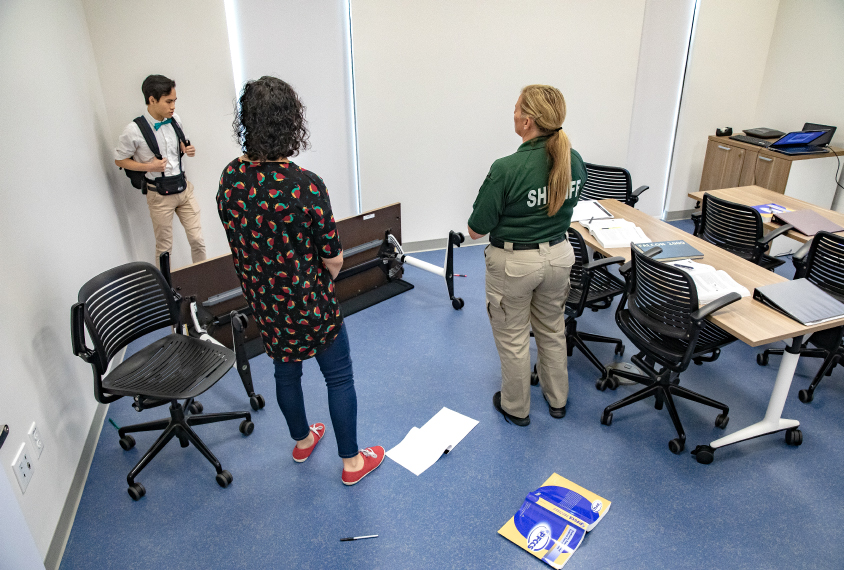

A training Gardner and her colleagues developed for Florida police officers goes one step further: It includes a role-play session with actors, some of whom are autistic, in realistic settings, such as a home and a big-box store. The simulations allow officers to practice de-escalation, Gardner says, preparing them to use their new skills in real life. “Through that practice and having that safe space to fail and talk through it, [officers] really make so many more gains than just sitting through the presentation portion of the training,” Gardner says. “The simulation portion helps them refine the knowledge and integrate it into practice.”

To make training more accessible to smaller police departments, researchers are also developing virtual trainings along similar lines. Vicki Gibbs, a research manager at Autism Spectrum Australia and former police officer, made sure to include clips from interviews with eight different autistic people in her online training for Australian police. “If they remember nothing else, they’ll remember those eight people,” Gibbs says.

Mixed messages:

Many advocates argue that training alone will not prevent violent police encounters — especially when underlying racism and ableism go unaddressed.

“Everyone under the sun has had a terrific idea about what should be done [about police violence],” says Camille Proctor, executive director and founder of The Color of Autism Foundation, a nonprofit that trains Black parents of autistic children on the ins and outs of diagnosis and services. “They don’t have the key. The key is, you’ve got to get police to stop killing Black people.”

The takeaway lessons from autism training — be patient, don’t touch people unnecessarily, speak in a low, calm voice — may conflict with other, more foundational training officers receive, particularly in high-stress situations, experts say. “What we’ve been trained to do in high-stress tactical situations is go to that next step to bring greater control,” Zink says. “But authoritative behavior that works for neurotypical people doesn’t work for autistic people.”

That authoritative behavior kicked in for the Salt Lake City, Utah, officers who responded to a call about Linden Cameron, a 13-year-old autistic boy in the midst of a mental health crisis, in early September. Those officers did have some mental health training, Salt Lake City Police Department spokesperson Detective Greg Wilking told The New York Times. But Linden’s mother had told the dispatcher that her son might have a prop gun. When the boy didn’t follow the officer’s orders to get down on the ground, they shot him multiple times. Linden survived but was hospitalized for weeks with injuries to his shoulder, ankles and internal organs, his mother told CNN.

“If you have 50 hours of training on how to make sure you’re in control at all times and tackle people, and then four hours of training on dealing with autistic people, you’re not going to be acting on those four hours of training in a crisis,” says Sam Crane, legal director at the Autistic Self Advocacy Network.

Despite the fact that many officers say they feel more confident in their ability to interact with autistic people after training, a small survey of autistic people who’d had police encounters in Canada found that more than half were unhappy with those interactions, with many respondents reporting feeling uncomfortable, anxious and afraid. “There’s this gap between what the police are satisfied with and what members of the public who are autistic are experiencing and their levels of satisfaction,” Drapela says.

Autism training may also be worthless unless it includes accountability, such as penalties for officers who don’t put those lessons into practice, advocates say. “I want a cop to have to think twice before they act,” says Kim Kaiser, program director at The Color of Autism. “They should know that the consequences are going to be swift and harsh.”

Some experts and advocates are pushing for other ways to protect autistic people. The Color of Autism’s parent classes include a module on police interactions, instructing parents to teach children to keep their hands out of their pockets, to make eye contact with officers and to disclose their diagnosis. Virtual-reality headsets might help autistic people practice these interactions, according to a small 2020 study.

And chance encounters between autistic people and the police might be safer if they already knew each other. In some places, autistic people can submit their information to a department’s autism registry, introduce themselves at local precincts or attend community events. In St. Paul, Minnesota, officers check in with autistic people and their families after a police encounter to build trust. It helps the officers, too, Zink says. “The more autistic people you know, the easier it is to recognize and deal with it, and the more success you have on these calls.”

These tactics aren’t always practical and can feel like an invasion of autistic people’s privacy. “You can’t take [your child] to every precinct in every borough,” Proctor says. Instead, some researchers say autistic people and their families would be better served in a crisis by friends, neighbors and mental health professionals than by police. Soares and his colleagues, for example, recommend that autistic people and their families create a ‘community watch’ to keep autistic people safe and reduce emergency calls.

Police should also team up with social workers, mental health experts and other non-law-enforcement professionals, Soares says. “We cannot expect officers to become mental health experts. But the awareness and ability to collaborate will help them improve outcomes.”

And non-autistic people need to refrain from calling the police immediately when they see an autistic person behaving in ways they don’t understand — especially when the person is Black, Crane says. “There are situations where no one should be responding. Just because someone’s different, it isn’t actually an emergency.”