Whiz kids

For many years, autism was considered synonymous with intellectual disability. A new study shows that perception is inaccurate.

The public’s view of autism tends to veer between two extremes: most people with autism are either savants, gifted with uncanny powers of memory and reasoning, or they are isolated beings — ’empty fortresses,’ in the words of a famously discredited book.

Clinicians know that neither of these stereotypes accurately describes the majority of people with autism. Even so, for many years they themselves continued to describe autism as almost synonymous with intellectual disability, repeating the old statistic that up to 75 percent of people with autism have intelligence quotients (IQs) below 70.

New research is showing that that figure is vastly overstated. According to an epidemiological survey published in March, only 55 percent of children with autism have any kind of intellectual disability, and fewer than one in five have moderate-to-severe intellectual handicaps.

The study also challenges the traditional assumption that individuals who score much higher on performance IQ versus verbal IQ tend to be more socially impaired and have bigger heads.

Most of the children in the study have similar verbal and performance IQs, and the small number who have a slight disadvantage in verbal IQ are no more socially impaired than the rest, based on their scores on the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, the gold standard assessment tool for autism.

The study, part of the U.K. Special Needs and Autism Project (SNAP), focused on 127 children aged 9 to 14 years old with an autism spectrum disorder. About half of the children have an IQ below 70, though the bulk of those scores are in the range of mild to moderate disability, the researchers found.

Slightly more girls than boys in the sample have an intellectual disability, perhaps reflecting the fact that autism is diagnosed less often in mildly affected girls than in girls with more severe disability. Since there are only 14 girls in the sample, though, it is difficult to judge.

Only 7.4 percent of children in the sample have IQ scores below 34, the cut-off for severe disability. However, fully one-quarter of the children in the study are of average intelligence, with a sliver scoring above 115.

The researchers note that those with higher IQs are most likely underrepresented in their study, which includes only children who have a medical diagnosis of autism and who receive assistance in school.

The real surprise in the data is that adaptive skills — social and emotional abilities needed to navigate daily life — are significantly lower than IQ scores among the children in the study.

This gap between intelligence and social functioning is particularly wide among those with higher IQs — a 35-point gap in some cases, proving once more that intelligence is not the best measure of ability to function in the world in children with autism.

Even so, the study goes a long way towards refuting pernicious assumptions about the abilities of children with autism. The findings once again remind us that old assumptions must be continually reexamined, and that the primary deficit in autism is not intellectual, but social.

Recommended reading

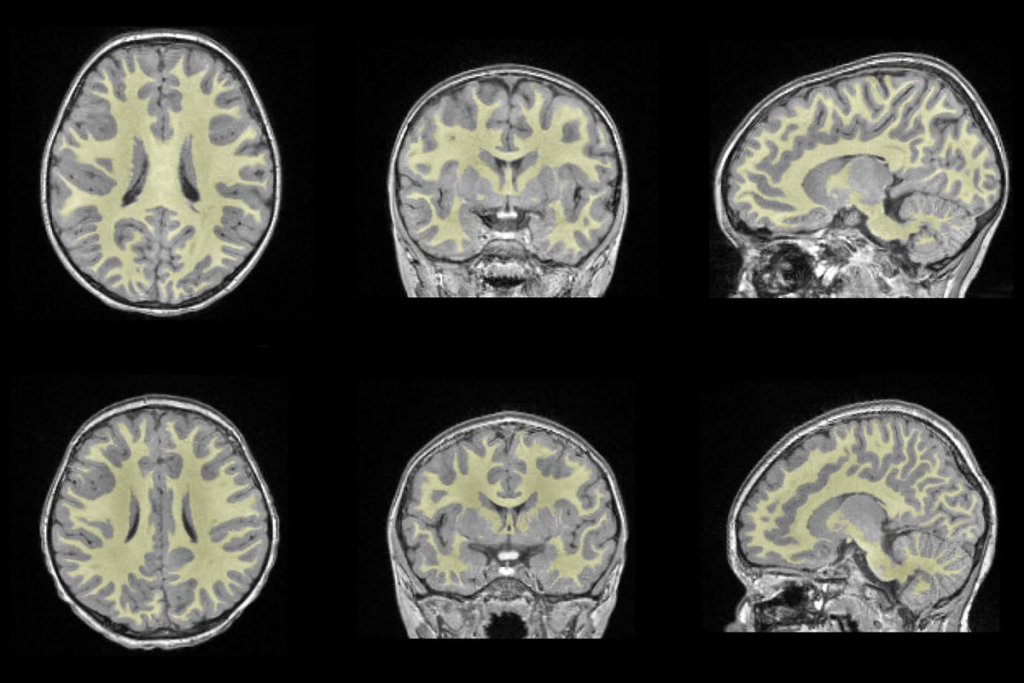

White-matter changes; lipids and neuronal migration; dementia

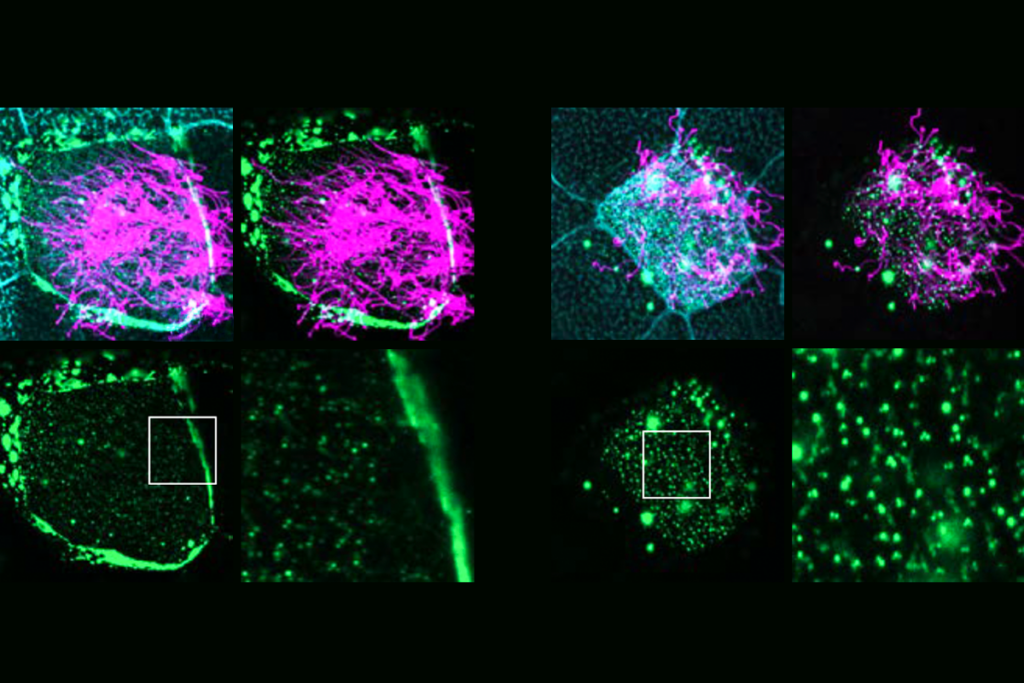

Many autism-linked proteins influence hair-like cilia on human brain cells

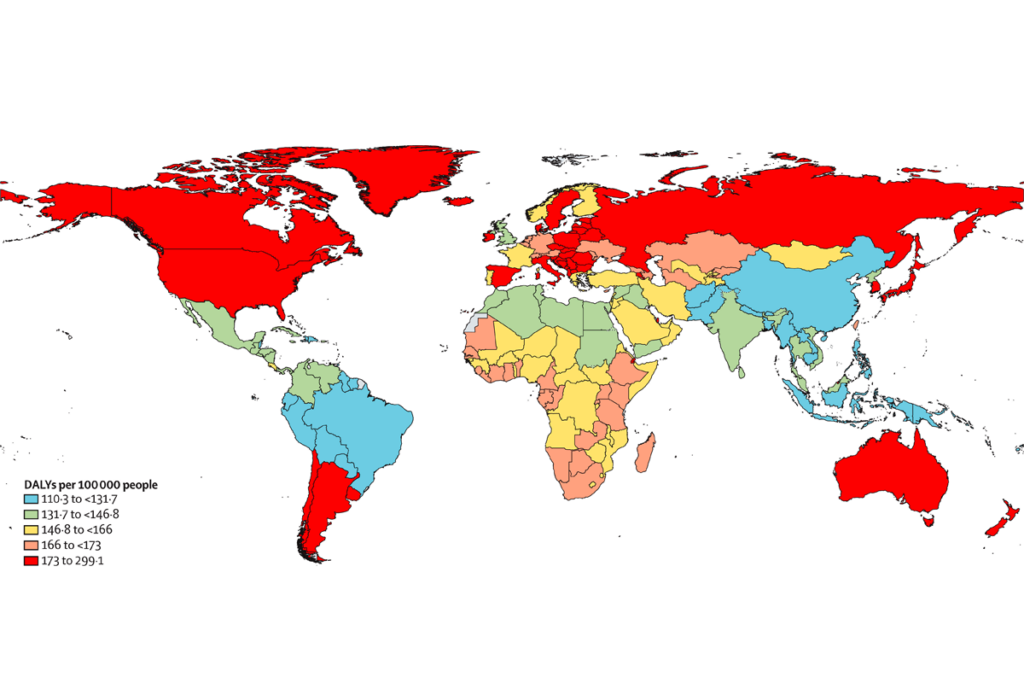

Functional connectivity; ASDQ screen; health burden of autism

Explore more from The Transmitter

David Krakauer reflects on the foundations and future of complexity science

Fleeting sleep interruptions may help brain reset