Autism researchers like to say, “If you’ve seen one kid with autism, you’ve seen one kid with autism,” a wry acknowledgement of the condition’s bedeviling heterogeneity. In a paper published last month in JAMA Pediatrics, researchers took a crack at parsing that heterogeneity through the lens of developmental milestones such as smiling, crawling, walking and speaking.

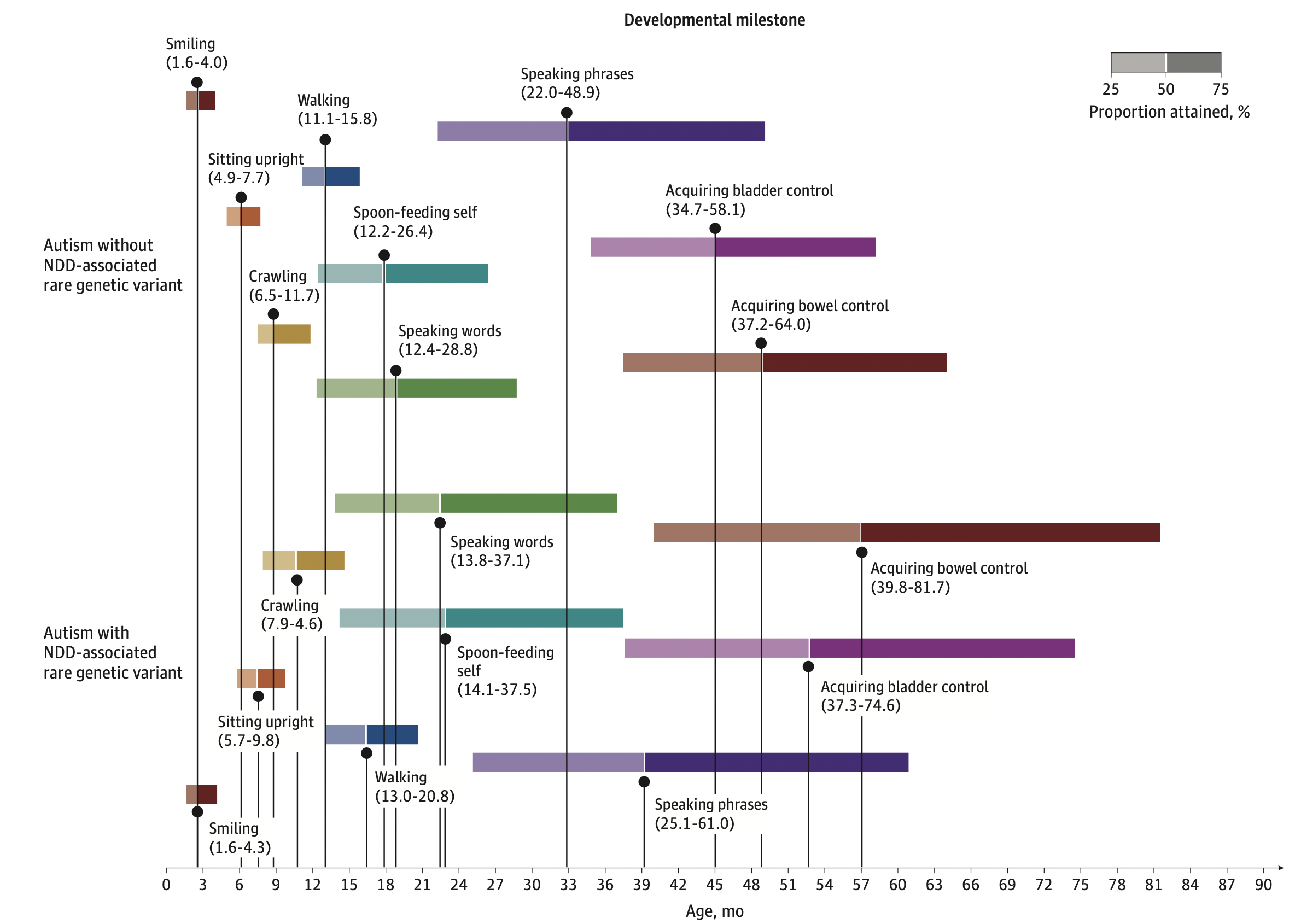

Autistic children often reach key milestones late, but the timing varies widely. By combining data from four different autism cohorts, the team amassed a large enough sample — more than 17,000 autistic children and 4,000 non-autistic siblings — to link patterns of developmental delays with factors such as sex, age at autism diagnosis, co-occurring intellectual disability and rare genetic variants associated with autism or other neurodevelopmental conditions.

As it turned out, the timing of various early milestones was also linked to a child’s research cohort, likely reflecting the shifts in autism diagnosis over the past quarter century. Autistic children from earlier cohorts, for example, tended to show greater and more variable delays.

That finding suggests it’s important “for everyone who’s working in autism to bear in mind not only that there’s vast heterogeneity, but it’s an unstable form of heterogeneity,” says lead investigator Elise Robinson, an institute member at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Spectrum spoke to Robinson and Susan Kuo, a postdoctoral researcher in Robinson’s lab who conducted the analysis, about what the results mean for autism — and for autism research.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Spectrum: Why are developmental milestones important for understanding autism?

Elise Robinson: Clinically, the nature and degree of developmental delay is quite meaningful when it comes to understanding the types of supports and resources that people and families might need. In terms of research, there’s a lot of reasons as well, both in terms of better characterizing heterogeneity in ways largely outside of the core diagnostic traits and criteria for autism, but also because developmental milestones can be quite reliably measured. For example, it’s easier for parents and scientists to quantify, “What month did your child first walk across a room?” than it is for them to quantify, “On a scale of one to seven, how difficult is it for them to make friends?”

Susan Kuo: Some of the earliest signs that something is different about the development of a child is in the early developmental milestones. I thought this would be a way for us to be able to capture the most information about early development, because it’s just so universally monitored, even before a child is undergoing evaluation for autism. It’s just something parents are already starting to look at and think about and track.

S: Developmental delays were larger, on average, in children who were part of the earlier study cohorts you looked at. What’s the reason for this?

ER: As the prevalence of autism, as measured, has increased, the majority of the increase has taken place through increased diagnosis in individuals with lower support needs. Which can mean a lot of things, but it certainly on average means individuals with lower rates of co-occurring intellectual disability or global developmental delay. And as that diagnostic shift has occurred, the composition of the research cohorts reflects it.

SK: Some of these participants were recruited all the way back in 1997. So that was 25 years ago. And some were recruited fairly recently. So it allows us to start to see what might be potential differences across cohorts, given that in the past 25 years, we know that there’s been an expansion in the diagnostic criteria for autism.

And these are different cohorts with very different recruitment and ascertainment strategies. For example, one recruited only families in which it was known that there was just one child and no other immediate relatives with autism — whereas other studies often were including families in which there were two children or more, or two first-degree relatives with an autism diagnosis.

S: Going forward, what should autism researchers keep in mind about this variability in developmental delays across time and cohorts?

ER: A few things. Researchers should be aware that correlation structures within their datasets are likely to be unstable across time and place. If you’re doing, really, most things that involve relating one variable to another within an autism dataset, those relationships have the potential to be unstable and to shift over time and between cohorts.

We see that already simply with regard to genetic associations to autism that are done statistically. As the composition of the cohorts changes, it increases the probability that findings that were true positives in the previous study will not replicate in the next study, or they’ll look different. But the same is true for non-genetic research. The same is true for phenotype research, treatment trials, everything where x to y is being related. That relationship could change.

S: It sounds like it makes it harder to replicate results.

ER: Yeah, I think that’s true in and outside of genetic research on autism.

S: What can we do about that?

ER: I don’t think the answer is to throw our hands up in the air. It’s to (a) try to overpower it with sample size and (b) try to leverage it. Particularly in the context of a highly heterogeneous diagnosis, identifying the things that are most relevant to the largest number of people is not only still important, but probably potentially exceptionally important. And identifying the biological differences or phenotype or behavioral or cognitive or medical properties that do seem to be the most stable can help you identify what’s worth focusing on the most.

S: What does the finding that children who carry rare variants associated with autism have larger and more variable delays in developmental milestones tell us about autism genetics?

ER: We’ve known for a long time that most strong-acting genetic variants that are linked to autism are also associated with intellectual disability, and many — if not most, actually — have a stronger relationship to intellectual disability than they do to autism. And that is reflected in the development and health of autistic individuals who carry one of those variants. They’re more likely to have co-occurring global developmental delays.

S: What do you make of the fact that co-occurring intellectual disability seems to extend those autism-related delays for every milestone except walking?

SK: Walking is an early developmental milestone. But it requires a whole lot of coordination to happen. This could build into a lot more interesting research into understanding why walking might not be showing quite as much change compared with speaking words or phrases. They’re happening around the same time, developmentally speaking, but what’s happening in that time window, such that you’re not seeing so many changes in walking but potentially starting to see a lot of changes in speaking words and phrases? I think that’s very interesting to consider, moving forward.

S: Do your results have any implications for parents and clinicians who are watching or may be concerned about a young child’s development?

SK: Just being able to get a full picture of a child’s development is very helpful to understand when a child with autism might have co-occurring intellectual disability. It’s starting to become helpful to know whether they might have a rare genetic variant that could be identified through clinical genetic testing. And all of those things can maybe help us get a better understanding of when or why a child is developing on this timeline, their own timeline with their own progress.

ER: I hope so. Firstly, we do have data from children without an autism diagnosis in the dataset, and it captures the reality that there is an enormous amount of perfectly healthy and expected variability in development in children across the population. And then with regard to variability within autism, I hope that these results provide clinicians with a snapshot of clinical variability in developmental milestone progress in autism as it’s currently being diagnosed. That was largely the goal of the work from the outset and why it went to a clinical journal, a pediatrics journal.