Web of autism genes untangles slowly

A new study maps the many targets of the autism gene TBR1, but it’s just one small piece of a much bigger picture.

Last fall, two massive sequencing studies spit out 50 genes that they linked to autism as definitively as is possible for the field right now. These genes are no longer just candidates, one of the lead researchers, Matthew State, told me at the time. It’s time to call them ‘autism genes.’

Many of these autism genes are so-called ‘master regulators,’ controlling the expression of hundreds, even thousands, of other genes. For example, TBR1, one of the 50, influences the expression of 124 other genes, according to a study published 20 January in Autism Research.

This seemingly endless web of interactions can be daunting, but as I discovered when reporting for an article last fall, some researchers see it more as an opportunity than an impediment. They are confident that by systematically uncovering the targets of each gene and finding the overlap among them, autism’s origins might begin to emerge.

This is easier said than done, however. Finding the targets for each of these master regulators is “a massive amount of effort,” according to Harvard University geneticist Michael Talkowski.

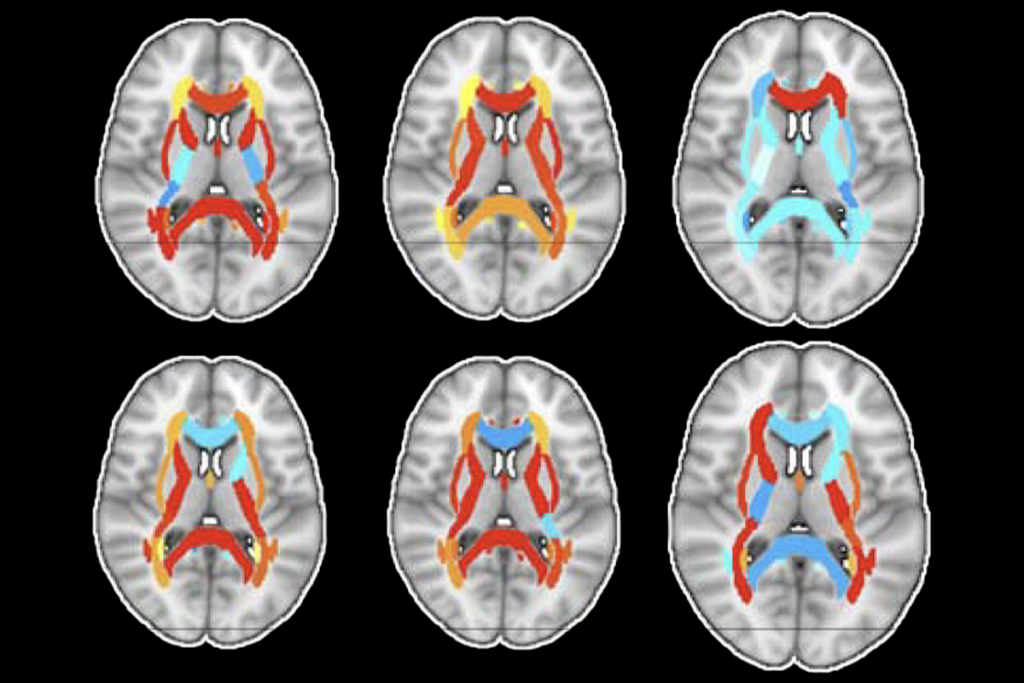

Researchers can use one of two methods to find a gene’s targets: pinpointing where on the genome the gene binds, or mutating the gene and assessing the impact on the expression of other genes. Neither is foolproof, but each gives an idea of the master gene’s reach.

Using both methods, Talkowski has been busy mapping the web of interactions for CHD8, which leads the charge among strong autism genes. The results, published in October in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, find that CHD8 binds near almost 6,000 possible targets. And deleting one copy of CHD8 changes the expression of more than 1,700 genes. Another study on CHD8, in press at Nature Communications, finds similarly massive numbers of targets.

In the TBR1 study, Yi-Ping Hsueh and her team at the Institute of Molecular Biology in Taiwan used the latter approach to home in on TBR1’s targets. They found that in mice, deleting one copy of TBR1 alters the expression of 124 other genes either up or down. Of these, 16 have some link to autism. Four of them — CHD8, GRIN2B, RELN and AUTS2 — are also on the list of the 50 top autism genes, and CHD8 and AUTS2 are themselves master regulators.

The study also looks for common pathways among TBR1’s 124 possible targets, but this seems premature to me. The answers probably lie not within one regulator’s targets, but in the commonalities among many more. Still, each piece is crucial, not to mention a heck of a lot of work.

Recommended reading

New organoid atlas unveils four neurodevelopmental signatures

Glutamate receptors, mRNA transcripts and SYNGAP1; and more

Explore more from The Transmitter

New method identifies two-hit genetic variation in autism; and more