Wearable device accurately scans brains in moving people

A new neuroimaging device that is worn like a helmet enables researchers to map the functional activity of a person’s brain as she moves her head.

A new neuroimaging device that is worn like a helmet enables researchers to map the functional activity of a person’s brain as she naturally moves her head1.

The helmet may help scientists to gather good imaging data from people who have trouble staying still, such as young children or those with developmental conditions.

The device uses magnetoencephalography (MEG), which measures the magnetic fields created when neurons fire. MEG offers advantages over other imaging techniques because it provides high-quality data on both the timing and location of neural activity, rather than just one or the other.

A standard MEG machine is a large, fixed device in which a person sits and inserts her head. It relies on superconductors as sensors, which must be housed in liquid helium at -270 degrees Celsius (-452 degrees Fahrenheit). Insulation protects the participant’s head from the extreme cold but also limits the clarity of signals. And having sensors embedded in the machine at fixed points means that head movements can distort the data.

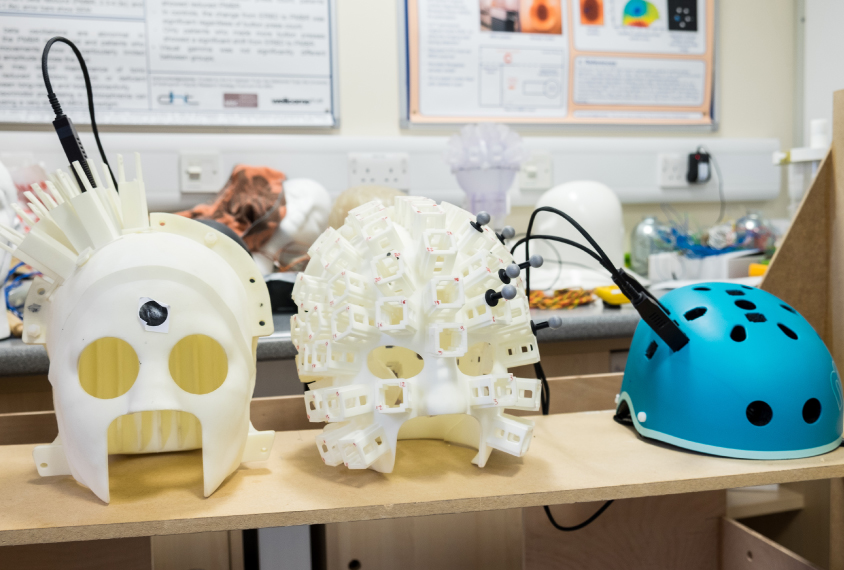

The new device uses sensors that work at room temperature. They line a 3-D printed helmet, shaped to fit the person’s head. The prototype includes only 13 sensors, which do not cover the entire helmet but are placed to target the particular brain area of interest.

To cancel out interference from Earth’s magnetic field, the team built two panels of electromagnetic coils that shield about 40 centimeters on each side. During scanning, people must keep their heads inside that space. But moderate head movement between the panels does not compromise the imaging data.

The researchers tested the system by measuring activity in a woman’s right sensorimotor cortex while she moved her finger. The woman performed six trials of 50 finger movements while remaining still, and six while moving her head naturally.

The quality of data was the same for all of the trials. The images also had a higher resolution than those from trials with the superconductor system. The results appeared 21 March in Nature.

In another trial, the woman bounced a ball on a paddle while wearing the helmet. Despite the erratic head and arm movement, the images were still of high quality.

References:

- Boto E. et al. Nature 555, 657-661 (2018) PubMed

Recommended reading

Too much or too little brain synchrony may underlie autism subtypes

Developmental delay patterns differ with diagnosis; and more

Split gene therapy delivers promise in mice modeling Dravet syndrome

Explore more from The Transmitter

During decision-making, brain shows multiple distinct subtypes of activity

Basic pain research ‘is not working’: Q&A with Steven Prescott and Stéphanie Ratté