We need precise measurements of sensory traits related to autism

Separating sensitivity to sensory stimuli from the response to the stimuli may help scientists understand the root cause of sensory traits in autistic people.

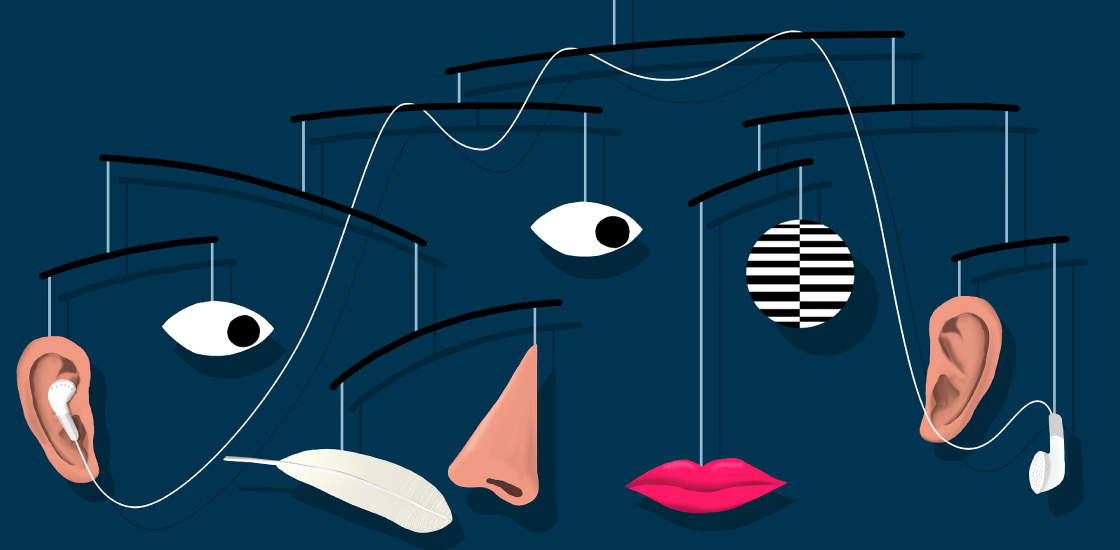

Many people with autism have atypical responses to sensory stimuli: Some appear to be hypersensitive, such that a clothing tag is unbearably scratchy; others may be so tolerant that touching a hot stove top yields a burn but no pain.

The prevalence of sensory issues among autistic people, as detailed through caregiver reports and questionnaires, may be as high as 70 percent1. Because of this, sensory traits are included in the diagnostic criteria for autism in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

Most of the work on sensory sensitivity in autism has relied on questionnaires and caregiver reports. Although these tools can assess the effects of sensory problems on real-world activities, they lack specificity: A person’s response to a stimulus depends not only on how she perceives it but also on how her brain processes it and on a host of behavioral and other factors. For instance, a child may appear insensitive to a stimulus because he is distracted by something, not because he perceives it differently from another child.

In a study published in May, researchers assessed sensory traits in neurotypical people using both a caregiver questionnaire called the Sensory Profile — which includes a series of questions about how people respond to sensory stimuli — and a visual detection task that provides a behavioral measure of sensory sensitivity2.

The two measures do not seem to track with each other, suggesting that they capture different facets of sensory function. This discrepancy is something any scientist studying sensory function in autism should care about.

Making sense:

Sensory traits can have profound effects on the daily life of autistic people: For example, an autistic child may not respond to her name, or may be so reactive to sound that she needs to cover her ears. These sensory challenges may contribute to problems with social communication and repetitive behaviors. For instance, a fascination with the look or feel of a certain toy may manifest as a restricted interest.

In the new study, the researchers measured sensory traits and repetitive behaviors and restricted interests in 90 neurotypical individuals aged 17 to 25. They used the Sensory Profile, which gauges the extent to which a person seeks out or avoids sensory stimuli, as well as how sensitive the individual appears to be to those stimuli. They also asked the participants to report the presence or absence of images made up of dim black and white stripes.

They used a standard scale to assess repetitive movements, rigidity, restricted interests and unusual sensory interests.

Scores on both sensory measurements track with scores on the repetitive behavior test, supporting the notion that sensory issues contribute to restricted interests and repetitive behaviors. But the two measurements do not correlate with each other, suggesting each is measuring something distinct.

The researchers conclude that the sensory perception task measures a person’s sensitivity to a visual stimulus, whereas the Sensory Profile provides a measure of the person’s ‘reactivity’ to the stimulus.

Reactivity is a much broader measure than sensitivity; it also encompasses affect, attention and motivation — all of which can contribute to a person’s response to the stimulus as reported on a questionnaire.

Sharper tools:

Regardless of whether a person with autism is hypersensitive to sound or hyperreactive to sound, she may benefit from noise-canceling headphones. But the difference becomes important when trying to understand the cause of the phenomenon. Scientists trying to uncover the genetics of sensory function in autism need to be careful in the way they interpret data from questionnaires and caregiver reports, given the complexity of what they are measuring.

To be sure, questionnaires and caregiver reports offer valuable insight into a person’s experience of the sensory world. But this study highlights the need for researchers to incorporate tools that detect the physiological sensitivity to a stimulus, not just the reaction to it.

One criticism of such tools is that they lack real-world significance: Does it really matter how quickly or accurately a child responds to the presence of a striped pattern on a computer monitor? Perhaps not for the child or the child’s family, but these kinds of data are important for research.

A tangible next step is to do this analysis in people with autism to see if the same relationships hold. I would also like to see a study examining the interrelationship between these two types of measurements. Knowing which facets of sensory features each measurement captures, and how these relate to core autism traits, could open up valuable new avenues in autism research.

Mark Wallace is dean of the graduate school at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee.

References:

Recommended reading

Expediting clinical trials for profound autism: Q&A with Matthew State

Too much or too little brain synchrony may underlie autism subtypes

Explore more from The Transmitter

Mitochondrial ‘landscape’ shifts across human brain