When monkeys that avoid social interactions inhale the hormone vasopressin, their sociability improves, a new study finds.

The results, reported today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, bolster the case for testing the hormone as a possible treatment for autism traits, says lead investigator Karen Parker, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University.

“The most important implication of these findings to me is that vasopressin treatment may be useful in managing similar behavioral [traits] in people with autism,” she says.

Vasopressin is structurally similar to oxytocin, a hormone long thought to promote social behavior, though recent work has called that idea into question. Low levels of vasopressin in cerebrospinal fluid are associated with impaired social behavior in monkeys and autistic children, Parker and her colleagues previously found.

This prior work hinted that doses of vasopressin might improve social function in both animals and people, but other research in hamsters and prairie voles revealed that injections of vasopressin could also increase aggression.

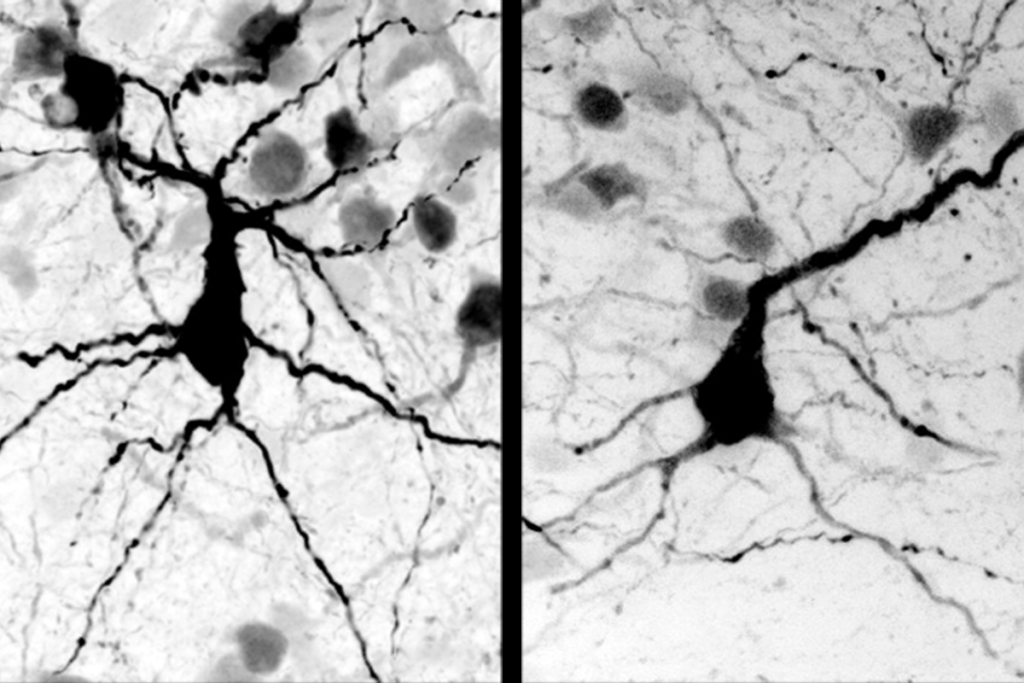

The new study involved eight male rhesus macaques at the California National Primate Research Center that naturally display low sociability—for instance, they spend less time than usual grooming other monkeys. These macaques also possess unusually low vasopressin levels in their cerebrospinal fluid.

“Monkey models are really important, because of features that may make them better than rodents in terms of translation of research to humans, such as more complex social behavior, and the way in which so much of our social behavior is guided by visual information, which is true of monkeys as well,” says Michael Platt, professor of neuroscience and psychology at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, who was not involved in the study.

These findings are “particularly exciting, because there are very few treatments for autism that address its core social [traits], which this treatment does,” says Karen Bales, professor of psychology, neurobiology, physiology and behavior at the University of California, Davis, who did not work on this study.

P

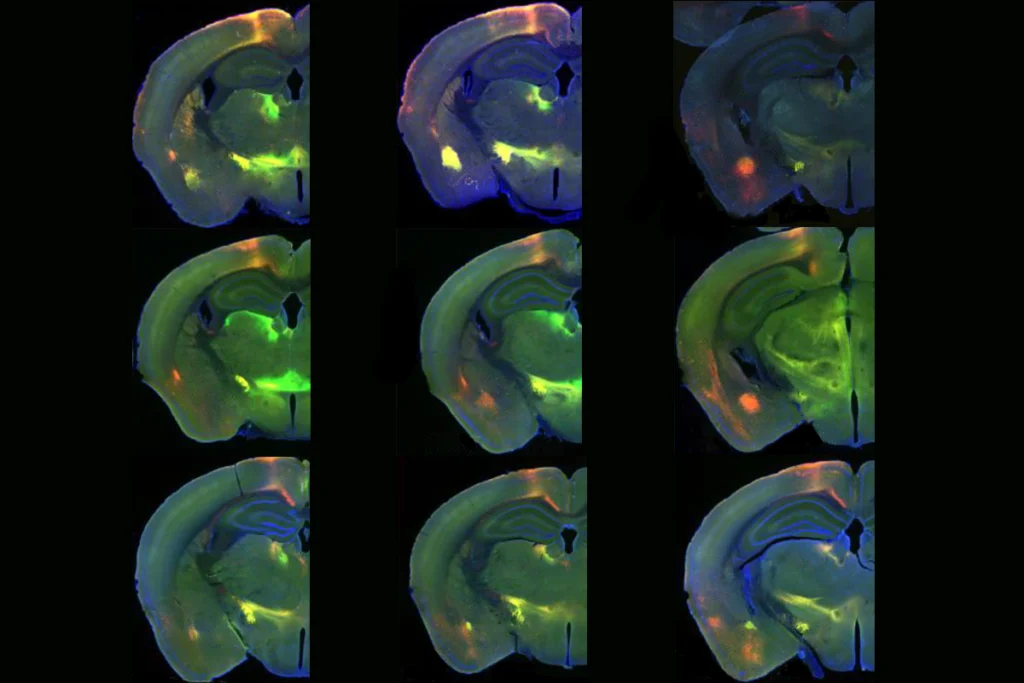

arker’s team built an apparatus in which the monkeys could receive a juice reward after they put their face in a mask that delivered a nebulized mist of vasopressin or placebo. Nebulized compounds enter cerebrospinal fluid more effectively than do those delivered by intranasal sprays or intravenous injections, previous research has shown. And letting animals take part in these procedures voluntarily, without the need for restraint or sedatives, minimized any stress-related confounding effects, Parker’s team suggests in their paper.Vasopressin levels rose in the monkeys’ cerebrospinal fluid after the nebulized doses of the hormone, suggesting that it likely entered the central nervous system. But the precise mechanism through which nebulized vasopressin influences the brain remains unknown, Parker says.

Before treatment, the monkeys lacked the ability to remember new monkey faces, although they could remember pictures of novel objects such as blenders, Parker and her colleagues found. And the animals displayed no response when shown videos of an unfamiliar adult male rhesus macaque performing friendly overtures such as lip smacking.

A single dose of vasopressin helped the monkeys remember faces as well as objects, and reciprocate friendly behaviors. It did not interfere with their object-recognition memory, nor did it increase aggressive responses to either friendly or aggressive behavior.

In a pilot phase 2A randomized clinical trial, 17 children with autism who received intranasal vasopressin for four weeks showed improvements in interpreting the mental states of others, recognizing others’ emotions via facial expressions, and other social abilities, Parker and her colleagues reported in 2019. Some of the children also had diminished repetitive behaviors and anxiety, and parents reported no increase in aggression. The team awaits the results of an eight-week phase 2B vasopressin treatment trial in more than 100 autistic children.

“If we obtain a positive outcome in the second vasopressin trial, we would like to conduct a multisite phase 3 vasopressin treatment trial,” Parker says. “I would like to more densely sample children’s behavior in real time at home, better ascertain the impact of vasopressin on daily functioning, and add brain-relevant readouts of treatment efficacy—for example, EEG.”

In the future, the scientists plan to test whether the treatment works better when given long term or with behavioral therapy, Parker says. They would also like to administer nebulized vasopressin to infant monkeys that display a high chance of low sociability “to test whether we can alter their developmental trajectories and prevent the onset of these social-interaction impairments,” Parker says. Because “it is widely thought that the most effective interventions for [autism] will manipulate specific pathways at an early age while the brain still retains much of its plasticity, this would be an important study to conduct.”

Future work should also consider more female animals, Bales notes. The new study evaluated males only. “Females are under-studied in autism,” she says, but rhesus macaques are likely not the best model in which to study female sociability, because the females of this species possess strong hierarchies affecting their behavior. “I’d love to see development of a similar model of low sociability for females, perhaps in a different species of non-human primate,” Bales says.

Vasopressin research should extend to executive function, which includes planning, carrying out complex tasks and self-control. “These can be deeply affected in people on the autism spectrum,” says Katalin Gothard, professor of physiology, neurology and neuroscience at the University of Arizona, who did not work on this study. “Such research cannot be done in all animals—[but] monkeys have the extraordinary skill to learn very complicated tasks.”

The major obstacle to conducting this type of research “is how costly it is,” Parker says. “Given that many agencies have deprioritized funding for animal models of [autism], we will need to identify suitable partners to enable us to continue this line of research.”