Unmasking schizophrenia

The word schizophrenia refers to the apparent separation of memory, thinking and perceptual abilities that trigger a disjointed personality in those with the disorder. But this split may also grant those individuals unusual abilities.

The word schizophrenia comes from the Greek skhizein, meaning ‘to split’ and phren, which means ‘mind’.

Schizophrenia now refers to the apparent separation of memory, thinking and perceptual abilities that trigger a disjointed personality in those with the disorder. But this split may also grant those individuals unusual abilities.

The disconnection between what the eyes see and what the brain perceives may be the reason that people with schizophrenia aren’t fooled by some visual illusions, according to a new study published in March in NeuroImage.

In the ‘hollow-mask illusion’, a well known test of visual ability, a mask of a human face rotates slowly around a vertical axis. When the mask has turned 180 degrees — and the inside of the mask is what’s visible — most people still see it as normal. It’s as if their brain refuses to see the face as hollow, presumably because that’s an extremely improbable sight in the real world.

In contrast, several studies have found that people with schizophrenia easily distinguish between normal and inverted photos of a face – something that has baffled scientists until now.

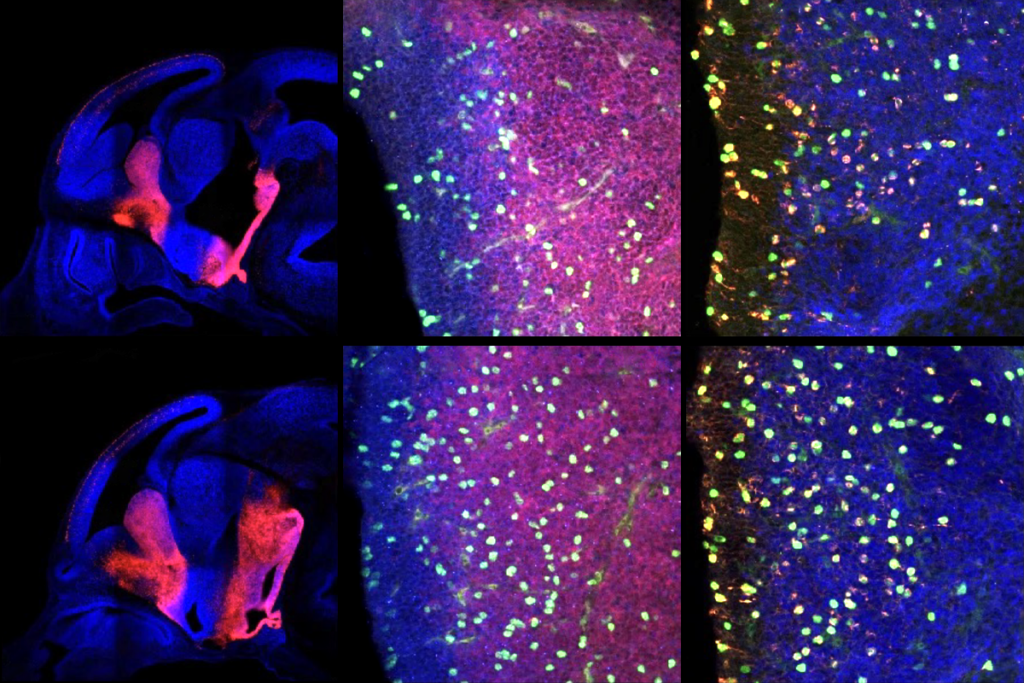

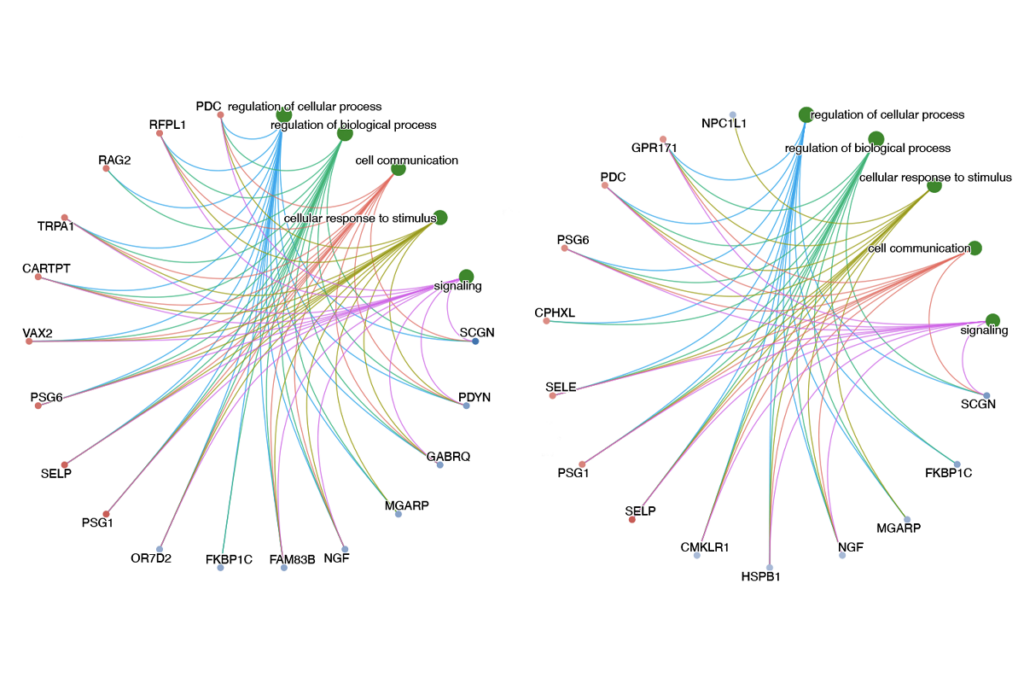

In the new study, the researchers found that confronted with an inverted face the brains of healthy people, but not of those with schizophrenia, show more activity in the fronto-parietal network. This brain region is involved in ‘high-level’ thinking processes, such as perceiving a combination of lines and shadings as a human face.

Increased activity in the region suggests that when a healthy brain receives unusual visual information from the eyes — the curved lines of an inverted nose, say — high-level regions such as the fronto-parietal network send out commands to low-level regions, such as the primary visual cortex, to ignore the strange sight, and still perceive what it sees as a nose.

In those with schizophrenia, those high- and low-level regions may not be properly connected, the researchers suggest. The study is small, and tested just 13 people with the disorder, but it’s still an intriguing look at the mysterious split.

Recommended reading

PTEN problems underscore autism connection to excess brain fluid

Autism traits, mental health conditions interact in sex-dependent ways in early development

New tool may help untangle downstream effects of autism-linked genes

Explore more from The Transmitter

Newly awarded NIH grants for neuroscience lag 77 percent behind previous nine-year average