Review: ‘Uncommon Sense’ exquisitely explores autism’s sensory experiences

The play dexterously depicts the struggles — sensory and social — of four characters who occupy distinct places on the autism spectrum.

Moose and Lali are nonverbal and live at home; Jess and Dan are more cognitively able and live independently. All four have autism. Together, these characters represent the broad spectrum of autism in the play “Uncommon Sense,” which premiered at the Sheen Center for Thought and Culture in New York City in October and is set to tour in 2018.

Performed with dexterity by the actors, the play depicts its star characters’ complicated and endearing struggles with basic communication, dating and friendships. It displays the anguish and frustration of their parents and family members over their challenges.

“Uncommon Sense” also exquisitely explores the sensory experiences of autism — through sight, smell, hearing, taste and touch. The play shows that for someone with autism, these senses may be ‘uncommon.’

The play starts with all four characters on stage, and through narration and behavior makes it clear that each one illustrates a different part of the autism spectrum. We then watch, often through actual window frames, as the characters move through different tiers of a multilevel stage while they experience the ups and downs, challenges and triumphs of autism.

As a researcher, I often think about how to develop assessments for each individual on the spectrum. I wonder whether these measures will be sensitive to changes over time and still capture one condition. I was impressed by the set design, which visually reflected these issues.

Giant jellyfish:

A real strength of the play is its video and audio projections of the characters’ circumscribed interests. Jess loves anime, and when we see her in her dormitory room, an anime character is projected onto a large banner that extends from the stage to the ceiling. By flooding our field of view, the banner powerfully illustrates the importance of anime in Jess’ world.

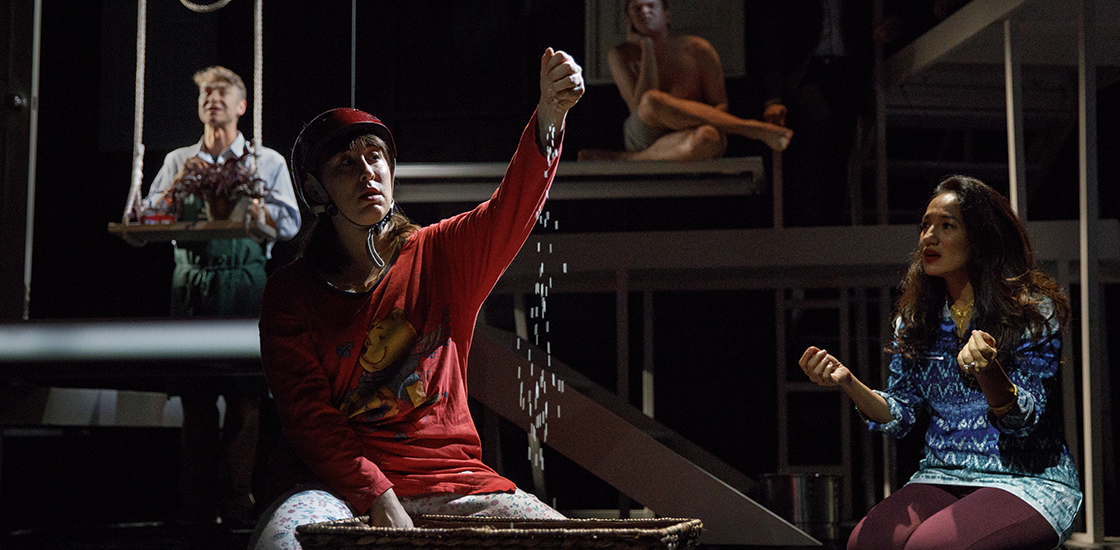

Lali adores sifting rice through her fingers and watching the grains drop onto the floor. In the play, the audience watches rice falling on large black screens, accompanied by soft music. This special effect cleverly shows the calming effects that falling rice has for Lali.

Moose loves water and jellyfish. In another beautiful scene, the stage is dark except for a softly lit, giant jellyfish made of fabric suspended above the stage, as Moose smiles and laughs, delighting in this world.

The audience experiences how disagreeable certain sounds can be for individuals with autism. Dan cannot tolerate snoring. We hear a screeching, loud, unpleasant sound that may be akin to what Dan hears, and we ‘see’ the snoring with green and white bubbles on a screen moving in synchrony with his girlfriend’s breath. When Moose runs away from his home, we hear blaring sirens, car horns and people yelling, showing us the sensory challenges people with autism may experience on city streets.

Jess, a college student, provides a window into how individuals on the spectrum navigate friendships. We watch Jess struggle with responding to Alex, a boy in her neuroscience class, when he asks her to tutor him and then makes it obvious that he wants a relationship. During a tutoring session, Jess rattles off facts about neurons, neurotransmitters and brain areas. But when Alex asks her personal questions, she falls silent. She quickly picks up a model of a brain and resumes her neuroscience tutorial, suggesting that her understanding of her brain is literal.

Playwrights Anushka Paris-Carter and Andy Paris cleverly portray a growing friendship that feels quite one-sided. Watching Jess made me think about the growing body of research into how to help young adults with autism make the transition to college and independent living.

Finger food:

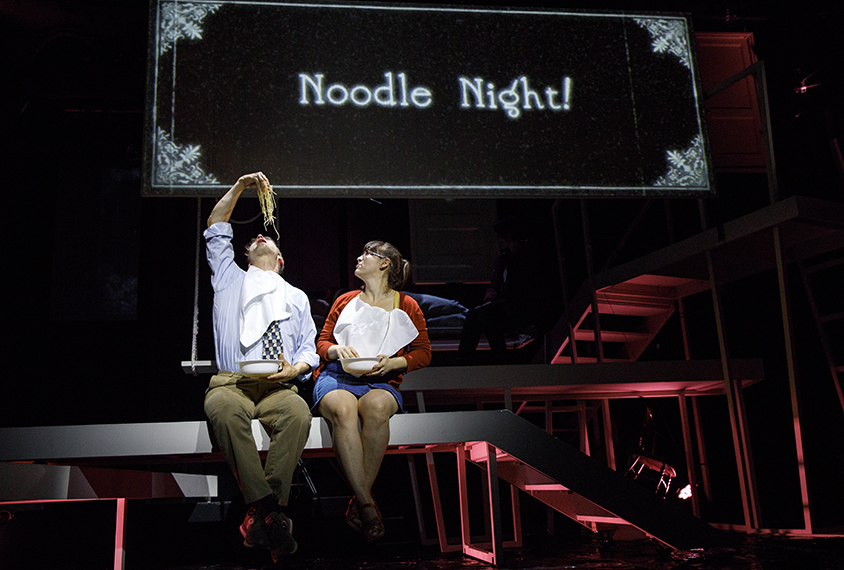

Unlike Jess, Dan seems interested in dating, yet has some troubles navigating a date. He invites a woman to dinner, but strongly dislikes eating food with a fork. At first, he tries to hide the fact that he uses his fingers to eat, by turning his back to his date and rapidly shoveling food into his mouth.

But of course she notices and starts eating pasta with her hands, too. Although I found the scene less realistic in portraying autism, it does nicely present some of the complexities of dating. It also illustrates an uncommon tactile pleasure relating to food.

Moose is a nonverbal young adult who frequently runs away from home. His actions, along with those of his parents, illustrate the complexities of parenting a person with cognitive difficulties, including having to decide whether to resort to institutional care. It also shows the strains a child like Moose can put on the parents’ marriage.

At one point in the play, Moose’s mother has a meltdown. Frustrated that her son can’t communicate to her, she cries to her husband, “He uses my brain to translate the world.” At this line, the room fell totally silent. I was struck by the apparent sensitivity of the audience to the issues facing parents and caregivers of children with autism.

Lali, the other nonverbal character, pointedly illustrates communication issues in autism. Lali ‘says’ nothing until halfway through the play, when a speech therapist brings her an iPad with Proloquo2Go, a communication app. The second time she uses the program, she types “Hillary for President.” Although this serves as comic relief — her mother asks the therapist if she thinks Lali is a Democrat — the response is not consistent with Lali’s apparent abilities.

Still, the play does a good job of showing how technology can be useful for communication. In our work, we have individuals complete research tasks on iPads to engage and motivate them to complete the work.

Uncommon perspective:

As someone who studies face processing, I was thoroughly entertained when a facial emotion detection video played as backdrop during a complicated social interaction. As Jess conveyed the events of an argument with her teacher, the facial features were changing in the video.

Through Jess’s narration, we could see that she was not picking up on his facial cues. The scene artfully demonstrated the subtle facial movements that make up complex emotions and the challenges that individuals with autism have in distinguishing among those emotions.

In these and numerous other scenes, the play takes on the task of presenting the broad range of behaviors in autism. The brain has a cameo, too, in supporting social communication in autism. Jess muses at the beginning of the play, “My mouth is connected to my brain, I think.”

There is a lot we don’t know about how brain circuitry goes awry in autism — and to its credit, the play doesn’t try to provide answers. The audience experiences a first date or falling rice from an uncommon perspective, but the play leaves the brain’s role in these experiences ambiguous.

Yet by artistically showing the nuances and struggles of those on the spectrum, “Uncommon Sense” leaves audiences with a better understanding of autism and its complexities.

Rebecca Jones is assistant professor of neuroscience in psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York.

Recommended reading

Autism traits, mental health conditions interact in sex-dependent ways in early development

New tool may help untangle downstream effects of autism-linked genes

NIH neurodevelopmental assessment system now available as iPad app

Explore more from The Transmitter

Five things to know if your federal grant is terminated

It’s time to examine neural coding from the message’s point of view