Un-common discovery

You’ve probably noticed that newsstands everywhere are covering a huge breakthrough in autism: the discovery of the first common genetic risk variants for autism.

You’ve probably noticed that newsstands everywhere are covering a huge breakthrough in autism: the discovery of the first common genetic risk variants for autism.

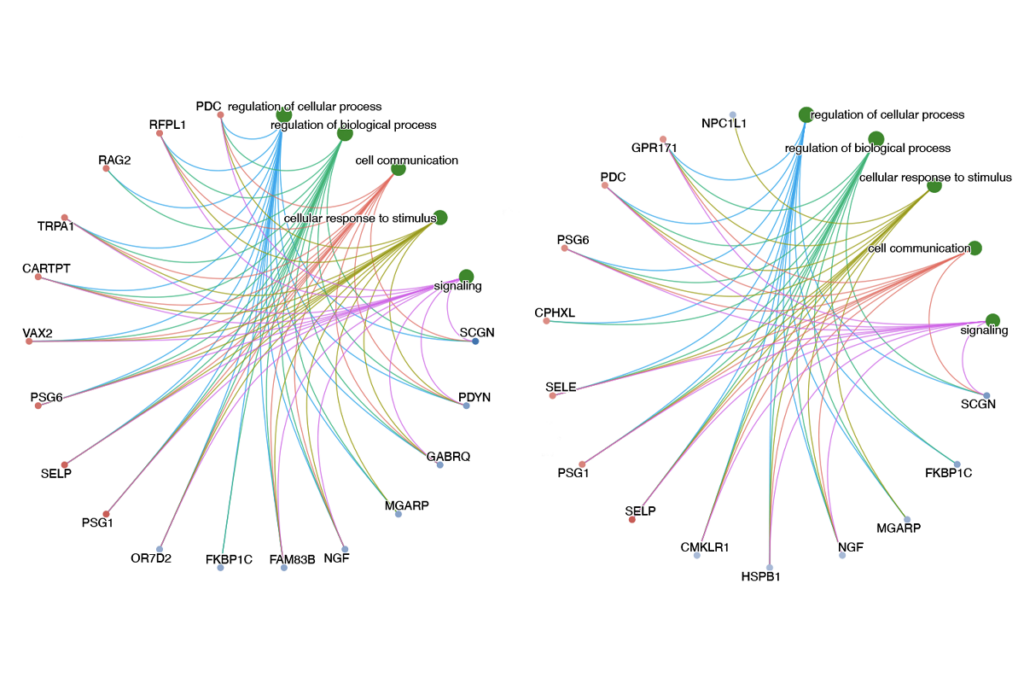

The study — by far the biggest to date — pinned six variants, all nestled between two genes on chromosome 5.

Adding even more grist to the mill, another study released yesterday also pointed to this region. Scanning about 900 families, that study found eight genetic variants that are more common in family members with autism than in their healthy kin. And again, all eight variants sit — you guessed it — in that same hot spot on chromosome 5.

The immediately obvious question is: what exactly are those variants doing there?

That would be much easier to answer if the variants fell within a gene, changing an important protein needed for a key pathway.

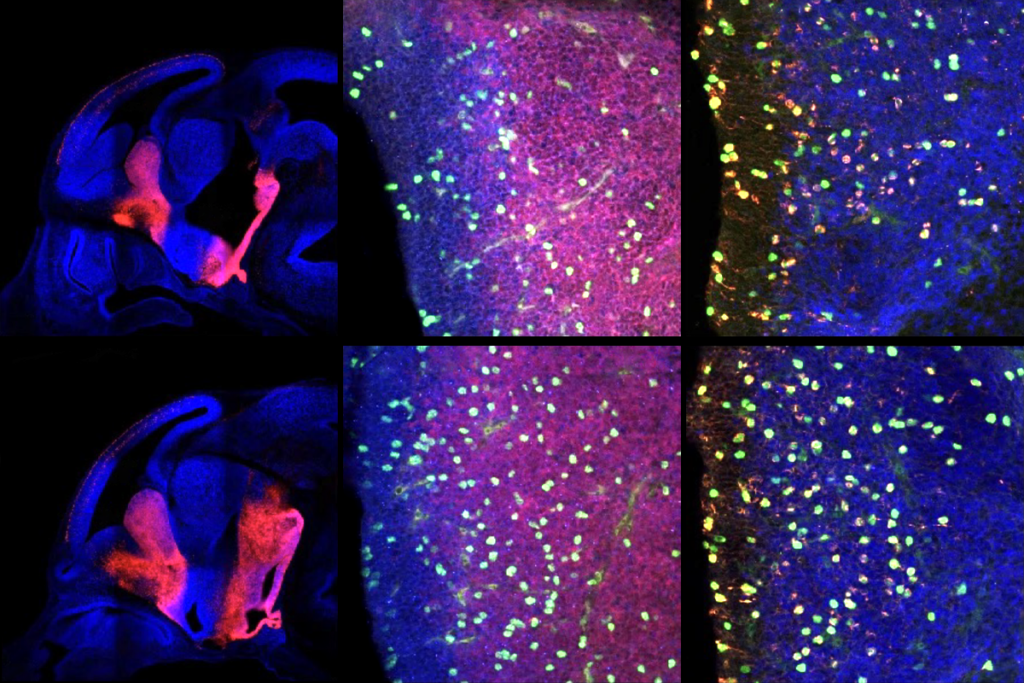

In this case, though, all we have to go on are the genes, called CDH9 and CDH10, that flank the variants. These genes make proteins that guide neurons to their proper place in the brain, help them connect to other cells and stick to each other.

That’s certainly intriguing because autism is thought to arise from problems with brain cell communication, especially in the synapses between neurons.

The variants’ interaction with CDH9 and CDH10 is for now pure conjecture. But it’s still exciting to see that common variants could have a plausible role in autism — especially given the past debates of their existence.

Before yesterday’s announcement, some scientists scoffed at the idea of common variants in autism, placing their bets instead on rare deletions or duplications.

Now we know that both types contribute to the disorder. It’s just that the common ones are harder to find.

Recommended reading

PTEN problems underscore autism connection to excess brain fluid

Autism traits, mental health conditions interact in sex-dependent ways in early development

New tool may help untangle downstream effects of autism-linked genes

Explore more from The Transmitter

Newly awarded NIH grants for neuroscience lag 77 percent behind previous nine-year average