Two drugs ease features of autism syndromes in mice

Drugs that block certain brain enzymes could help treat two conditions associated with autism.

Drugs that block certain brain enzymes could help treat two conditions associated with autism, a new mouse study suggests1.

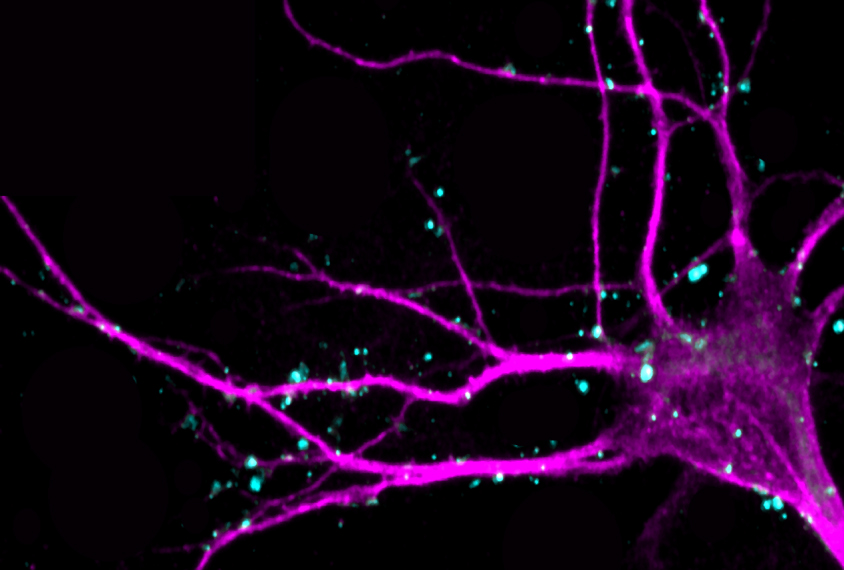

The study identified enzymes that regulate levels of the protein MECP2 in neurons. This protein is absent in about half of cells in Rett syndrome and is overproduced in a condition called MECP2 duplication syndrome. Both conditions are associated with intellectual disability and autism.

The researchers found that suppressing one of the enzymes with drugs normalizes MECP2 levels in a mouse model of MECP2 duplication syndrome. It also improves motor skills in the mice. Applied to other enzymes, the same approach could, in theory, boost MECP2 levels and treat Rett syndrome.

The drugs are not safe for use in people. But the study hints at the promise of similar drugs that might target enzymes involved in maintaining MECP2 levels.

“If we discover something that indirectly regulates MECP2 and that we can use safely, that could be an option for therapy,” says lead researcher Huda Zoghbi, director of the Jan and Dan Duncan Neurological Research Institute at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston.

The strategy the researchers used to identify the relevant enzymes could also yield targets for other conditions in which too much or too little protein is produced. For example, too little of the protein SHANK3 can lead to autism features and too much to hyperactivity, says Guy Rouleau, director of Montreal Neurological Institute and Hospital, who was not involved in the study.

Protein dials:

Zoghbi’s team set out to gently lower MECP2 levels in a mouse model of MECP2 duplication syndrome. These mice spend less time than controls exploring their surroundings, and perform poorly on a test in which they have to balance on a rotating rod. People with the syndrome also have anxiety and motor difficulties.

The researchers first engineered a line of human brain cells to express a fluorescent tag on MECP2. They used a method called RNA interference — in which a stretch of RNA binds to and blocks expression of a gene — to suppress each of 873 enzymes. They identified the RNA fragments that dim the cells’ glow, indicating a decrease in MECP2. They found four genes that, when blocked, have this effect.

They then made two sets of mice that each lack one of these genes. (They have not yet tested the other two genes.) One strain lacks the enzyme PP2A; the other is missing an enzyme called HIPK2. Both strains show decreased levels of MECP2.

The researchers then tested two drugs known to block PP2A. Each of the drugs lowers levels of MECP2 in mice by about 25 percent. This decrease is enough that the animals stay upright on the rotating rod as long as controls do. The findings appeared 23 August in Science Translational Medicine.

Expanded search:

Researchers could use the same strategy to identify drugs that lower or raise the expression of MECP2 and are safe for use in people. But the drugs must have moderate effects on their targets.

“The fact that either too much or too little MECP2 produces severe neurological impairment means that strategies for increasing MECP2 levels in, for example, Rett syndrome must operate within a fairly narrow concentration range,” says David Katz, professor of neuroscience at Case Western University in Cleveland, Ohio, who was not involved in the study.

Combining treatments with small effects on MECP2 levels may be the best therapy for conditions associated with MECP2, Zoghbi says. “We are going to have to treat someone for decades,” she says. “The safest way to do that is probably a combination so that we can adjust the treatment.”

The team is expanding their search for enzymes that boost or lower MECP2 levels by screening another 7,000 genes.

References:

- Lombardi L.M. et al. Sci. Transl. Med 9, eaaf7588 (2017) PubMed

Recommended reading

New organoid atlas unveils four neurodevelopmental signatures

Explore more from The Transmitter

The Transmitter’s most-read neuroscience book excerpts of 2025

Neuroscience’s leaders, legacies and rising stars of 2025