Twin study suggests large head size runs in autism families

Children with autism and their unaffected twins have heads that are significantly larger than average, according to a study published 16 January in the Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders.

Children with autism and their unaffected twins have heads that are significantly larger than average, according to a study published 16 January in the Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders1.

The study supports the idea that large head size is an endophenotype for autism — meaning that it may be a biological trait in both individuals with autism and unaffected members of their families.

About 20 percent of children with autism have macrocephaly, defined as having a head larger than that of 97 percent of peers matched by age and gender.

The new study, based on an analysis of 202 identical and fraternal twin pairs, confirms this rate. It also reports that twins tend to have about the same head size even when only one of them has autism.

“I think the main message is that yes, large heads are associated with autism, and yes, it’s probably at least partly due to genetics,” says Wendy Froehlich, instructor of child and adolescent psychiatry at Stanford University in California, and the study’s co-investigator. “But whatever is causing the large head size in itself is not enough to cause autism.”

The results directly contradict those from a 1995 British study in which researchers examined 45 twin pairs discordant for autism — meaning one twin has autism and the other does not2. That study found that 12 of the twins with autism, but none of the unaffected twins, had macrocephaly.

The results are “tremendously interesting,” says Janet Lainhart, professor of psychiatry at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, who was not involved in the research. “It doesn’t mean that one study is right and the other is wrong; it means that we have more to learn about all of this.”

Twin results:

Researchers have linked large head size to autism since the disorder was first described in the 1940s, and previous research suggests that macrocephaly may be inherited. For example, unaffected family members of people with autism are more likely than the general population to also have large heads3.

In the new study, researchers measured the head circumferences of twin pairs ages 4 to 18. They selected the twins from a sample of 1,157 pairs in which at least one twin had clinical evidence of autism. All are part of a registry compiled by the California Department of Developmental Services, a state agency that provides services to people with disabilities.

In each case, the researchers diagnosed at least one or both of the twins with autism using the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised and the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, both known as gold-standard tests for the condition. They then tested the twins with a battery of behavioral and cognitive evaluations, measured their heads and surveyed their parents for their heights and weights.

Among the twins with autism, 20 percent of boys and 27 percent of girls meet the criteria for macrocephaly. Likewise, among the unaffected twins, 15 percent of boys and 23 percent of girls have macrocephaly. (The difference in these two sets of numbers is not statistically significant.) The findings are in line with estimates of macrocephaly in boys with autism and higher than previous estimates for girls with the disorder.

The researchers also looked at 72 same-sex twin pairs, both identical and fraternal, in which only one twin has autism. In 36 pairs, the twin with autism has the larger head, and in 29 pairs, the unaffected twin has the larger head. The remaining seven pairs of twins have equal head sizes. The pattern is the same for both identical and fraternal twins.

The researchers found similar rates of macrocephaly among boys and girls, and comparable head sizes among twins who both have autism. Only six children in the entire study, or 1.5 percent, have microcephaly, or a smaller head than average, compared with the 3 percent rate in the general population.

Sharp contrast:

Although the new study shows compelling evidence that affected and unaffected twins have similar head sizes, it does have several limitations.

The new study does not include the twins’ socioeconomic status. Children from families with a higher socioeconomic status tend to have larger heads — a proxy for brain size — than those from families of lower socioeconomic status. For instance, children who receive better nutrition have larger heads, and children in emotionally deprived environments have smaller heads, Lainhart says.

Because families that volunteer for studies tend to be of higher socioeconomic status, Lainhart says she would like to see if the 202 twin pairs are representative of the 1,157 pairs originally identified.

Discordant twins having similar head sizes may merely be a coincidence and not an endophenotype, says Armin Raznahan, a senior research fellow at the Child Psychiatry Branch of the National Institute of Mental Health. He notes that because the researchers did not include a control group of unaffected twin pairs — because they ran out of funding, they say — it’s hard to know how head sizes in typical families compare.

Another explanation for macrocephaly lies in the twins’ physical measurements. The twins’ heights and weights generally matched their head sizes, meaning that children with larger heads may simply have larger bodies. But not all parents provided height and weight information for their children, and the researchers cannot be sure whether the information they do have is accurate.

“One of the limitations of the study is that we didn’t measure heights and weights when the kids were here,” Froehlich says.

Regardless of how head size is associated with autism, Froehlich says she will continue to measure it. If genetic tests don’t explain a child’s macrocephaly, she says, she orders sequencing of certain genes, such as PTEN, a gene associated with autism and macrocephaly. “I’m always checking head circumference,” she says. “It affects which genetic tests I order.”

References:

1: Froehlich W. et al. J. Autism Dev. Disord. Epub ahead of print (2013) PubMed

2: Bailey A. et al. Psychol. Med. 25, 63-77 (1995) PubMed

3: Fidler D.J. et al. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 42, 737-740 (2000) PubMed

Recommended reading

Sex bias in autism drops as age at diagnosis rises

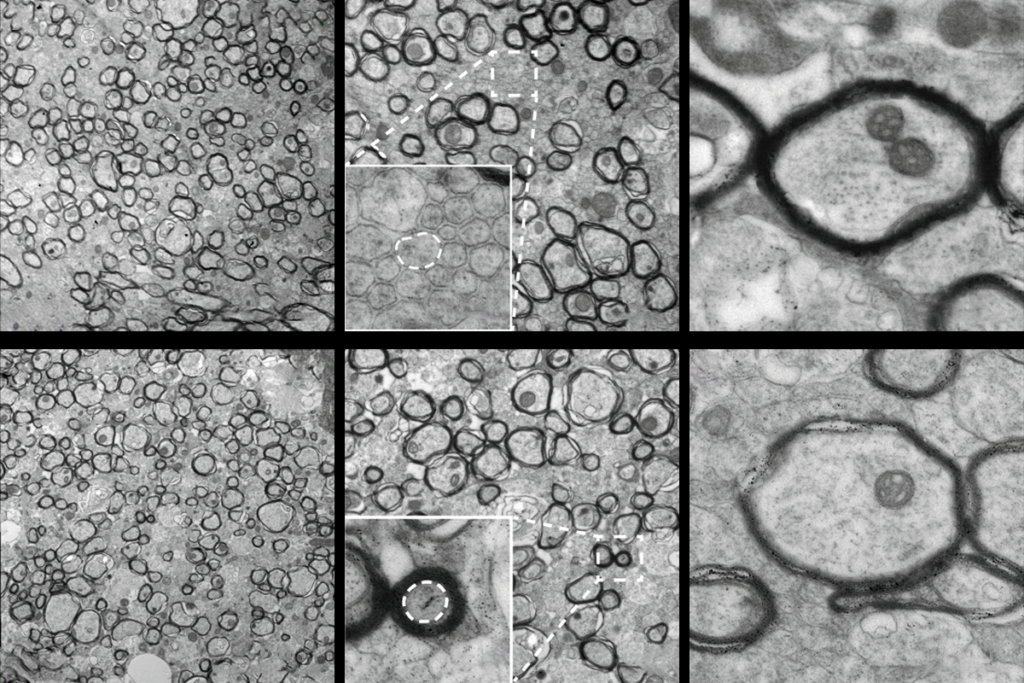

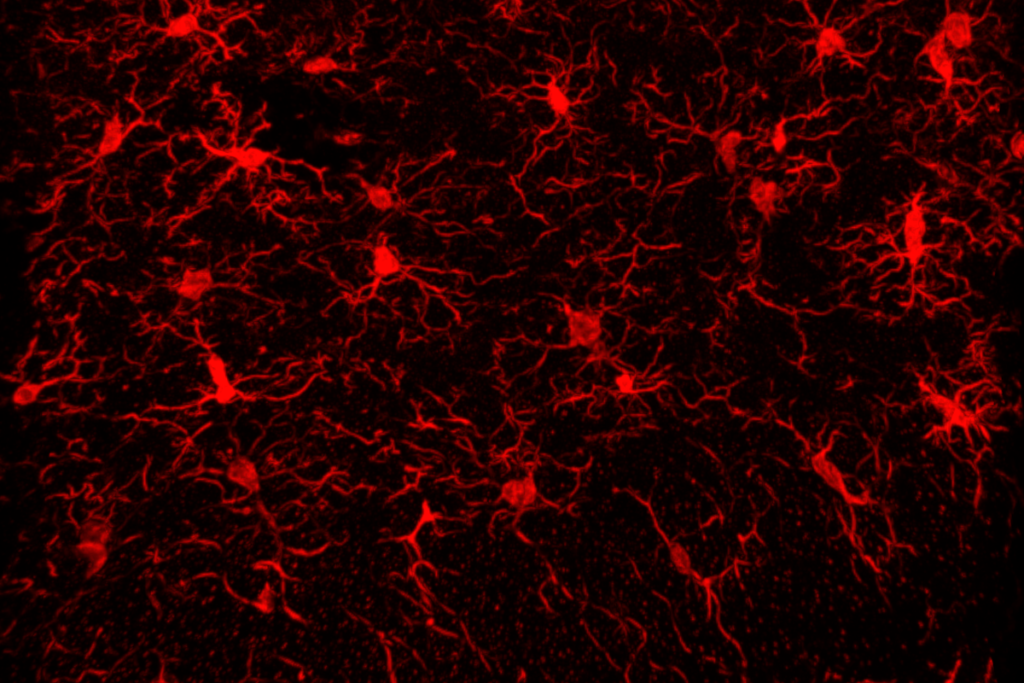

Microglia implicated in infantile amnesia

Explore more from The Transmitter

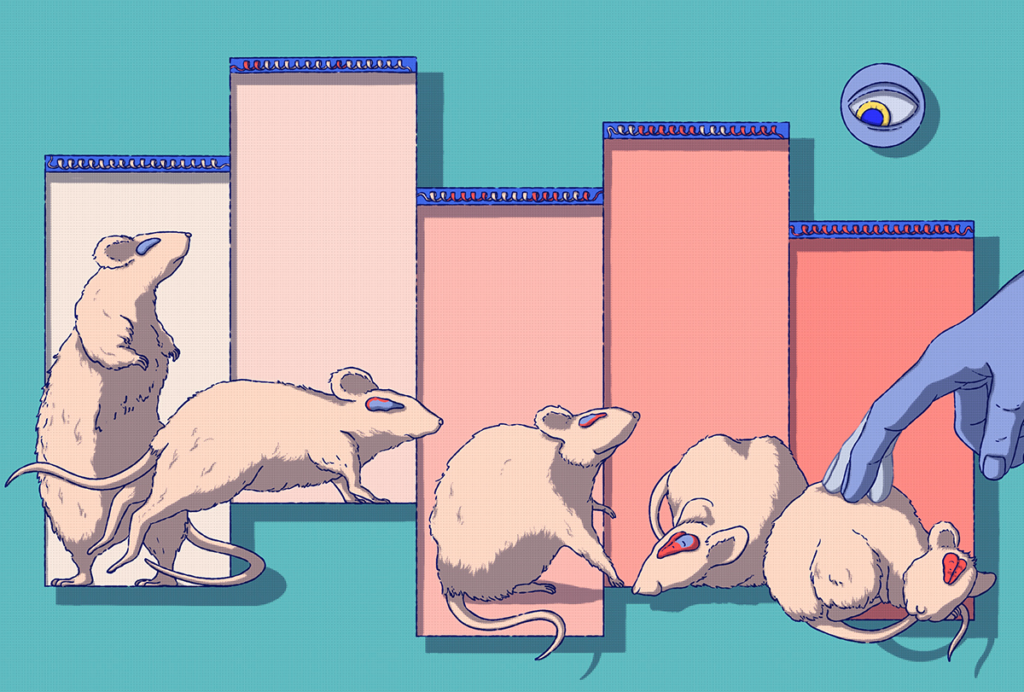

This paper changed my life: Ishmail Abdus-Saboor on balancing the study of pain and pleasure