‘Triple-hit’ study may help explain autism’s male bias

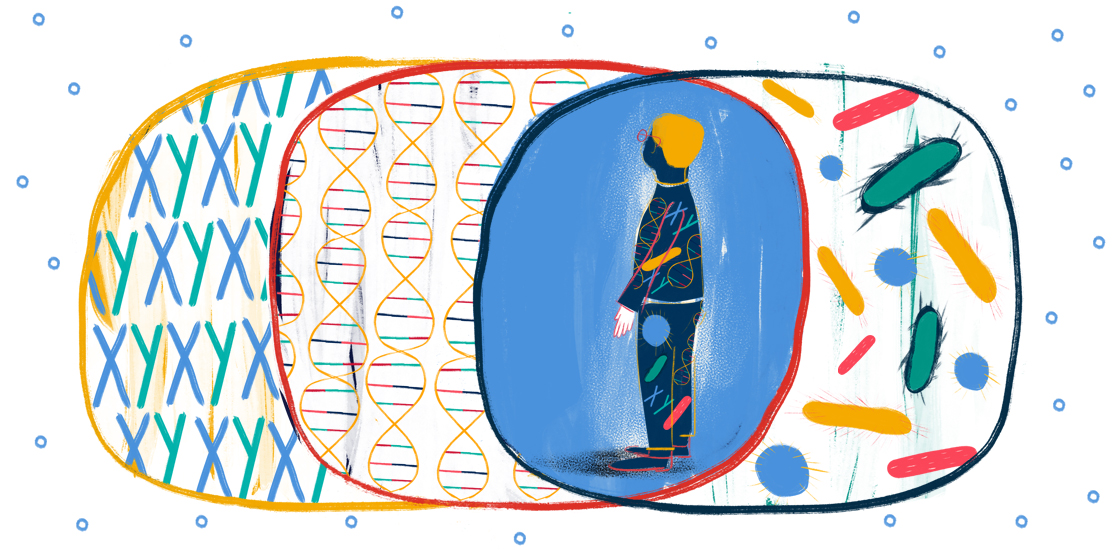

The absence of an autism-linked gene, combined with exposure to a mock infection, produces social deficits in mice — but only in males.

The absence of an autism-linked gene, combined with exposure to a mock infection in the womb, produces social deficits in mice — but only in males, according to a new study1.

The results suggest that a ‘three-hit’ model of autism risk — genes, environment and sex — could help clarify the gender disparity in autism. (More than four times as many boys as girls are diagnosed with autism.)

The results, published 7 February in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, provide proof of principle for this new hypothesis.

“This is the first explicit test,” says study leader Donald Pfaff, professor of neurobiology and behavior at Rockefeller University in New York City. His study looked at mice lacking CNTNAP2, a leading autism candidate. “There will have to be many other [studies] with other mutated autism-related genes and other forms of stress,” he says.

The new model adds sex to the traditional ‘two-hit’ models of autism risk, which look at interactions between genes and the environment. “One of the novel things of this paper is considering sex to be a hit,” says Larry Young, chief of behavioral neuroscience at Emory University in Atlanta, who was not involved in the work.

Muted cries:

The researchers exposed pregnant mice to lipopolysaccharides (LPS), a class of molecules that mimic a bacterial infection. Pups born to pregnant mice exposed to LPS are known to show autism-like social deficits. Molecules released by the maternal immune system in response to infection may affect the developing brain.

Some of the pups in the study lacked a working copy of CNTNAP2. Mice missing CNTNAP2 have impairments in social behavior and communication.

When the pups were 3 days old, the researchers recorded high-pitched cries, or ultrasonic vocalizations, that each pup made when separated from its mother. These cries may mirror the communication problems seen in autism.

Mice that have one of the three hits — that is, are either male, were exposed to mock infection in the womb or lack CNTNAP2 — emit fewer ultrasonic vocalizations than do female controls. Those with two of these risk factors emit even fewer cries. And those with three hits — males lacking CNTNAP2 that were born to LPS-exposed mothers — make the fewest cries of all.

“They’ve taken a very complicated design and presented it in a way that is very easy to understand,” says Jason O’Connor, assistant professor of pharmacology at the University of Texas, San Antonio. “So I think, conceptually, it’s an important step for the field.” O’Connor was not involved in the work but has studied CNTNAP2 mutants exposed to infection in the womb.

Memory mechanism:

Once the mice in the new study reached adulthood, Pfaff’s team noted a change in their social behavior. Mice with zero, one or two hits are eager to sniff and investigate a new visitor to their home cage; their interest in the mouse wanes when it visits again.

Mice with three hits don’t show this pattern. They spend a relatively brief amount of time sniffing a visitor mouse, no matter how many times it has visited.

Mice with the triple hit also have altered gene expression in the hippocampus, the brain’s memory center. For example, in the left hippocampus, these mice show dampened expression of a gene for corticotropin-releasing hormone, a molecule involved in the stress response.

Finding a molecular alteration in the brain bolsters the results of the behavioral studies, Young says. The hippocampus and the stress response are both implicated in autism.

The three-hit combination may also alter gene expression in other brain regions, Pfaff says. In addition, genes in other pathways may contribute to the mice’s altered social behavior.

References:

- Schaafsma S.M. et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 1383-1388 (2017) PubMed

Recommended reading

New organoid atlas unveils four neurodevelopmental signatures

Explore more from The Transmitter

Snoozing dragons stir up ancient evidence of sleep’s dual nature

The Transmitter’s most-read neuroscience book excerpts of 2025