How treating sleep may ease all forms of autism

Behavioral interventions and medications can help children with autism-related syndromes sleep better, but the treatments must be tailored to the cause of each child’s sleep disturbance.

In a clinic I run at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), I see children who have various genetic syndromes associated with autism. These children have a wide range of features, including intellectual disability, language problems and seizures. But they have one thing in common: poor sleep.

The inability to fall or stay asleep, called insomnia, can have far-reaching consequences. Sleep helps us to consolidate memories, learn and grow. Insomnia can aggravate cognitive and social and communication problems, behavioral challenges and anxiety; it can also exacerbate seizures.

Behavioral interventions and medications can help children with autism-related syndromes sleep better, but the treatments must be tailored to the cause of each child’s sleep disturbance.

For instance, dup15q syndrome is a condition characterized by intellectual disability, seizures and autism, caused by an extra copy of a stretch of DNA on chromosome 15. A child with this syndrome who wakes up throughout the night because of seizures is likely to need a different treatment than a child with, say, fragile X syndrome, who has difficulty falling asleep because of anxiety.

Understanding how sleep patterns vary across these genetic syndromes, and how disrupted sleep affects development, may improve our ability to treat each child’s specific needs. For this reason, I ask families about sleep at every clinic visit and carefully track their child’s response to sleep treatments.

Dream scheme:

Many of the children I see at the UCLA Developmental Neurogenetics Clinic are sleep-deprived, and their parents are usually exhausted, too. Sleep problems affect up to 70 percent of children with autism, compared with about 20 percent of children in the general population1,2.

Sleep disturbances can be particularly severe among children who have genetic syndromes associated with autism. For instance, some children with CHD8 mutations are awake for days at a time3.

Many parents of children with complex neurodevelopmental conditions do not complain about insomnia because other issues, such as epilepsy, require more urgent attention. In other words, sometimes sleep problems are a lower priority than a child’s other challenges. I always ask about sleep problems, as poor sleep is associated with problems with daytime behavior, adaptive skills and cognitive function 3,4.

The first step toward improving sleep is to identify the modifiable factors that could keep the child up at night. These include the child’s evening routine, exposure to light and screens before bedtime, hunger or gastrointestinal distress and sensory sensitivities. Certain medications, such as antiepileptic drugs, stimulants or mood stabilizers, can also disrupt sleep.

After taking inventory of these modifiable factors, we can begin to make changes. For instance, I may work with parents to develop a more consistent sleep routine or modify the child’s medication regimen. I strongly discourage parents from sleeping with their children, as this can undermine healthy sleep for both parties.

If these behavioral strategies do not help, we can explore medications. I often recommend melatonin, a hormone naturally released by the brain to regulate our sleep-wake cycle. Melatonin can help people fall asleep, but it does not prevent nighttime awakenings.

If melatonin is not the right solution, I consider a class of drugs known as alpha agonists. These medications are commonly used to treat high blood pressure. I start with a low dose and monitor children carefully for daytime sleepiness or irritability.

Tracking sleep:

I ask parents to keep a sleep diary, in which they log their child’s bedtime each night, the time the child actually fell asleep, and the timing and duration of any nighttime awakenings. This helps me track the effectiveness of interventions and identify triggers for insomnia. I order a formal sleep study only if I suspect sleep apnea or nocturnal seizures or if I cannot determine whether the child’s sleep is truly disrupted.

Although sleep diaries can tell us much about the overall sleep schedule and pattern, we need more sophisticated tools to assess the impact of poor sleep on daytime behaviors. There are standardized questionnaires for assessing sleep-related behaviors in children, but we need revised questionnaires for children with significant intellectual disability, language impairment or developmental delay. Such questionnaires, administered during routine clinic visits or before and after an intervention, could give us rich data about sleep over time.

National registries sponsored by advocacy groups for rare genetic conditions are beginning to collect detailed information about sleep. Ultimately, better data will lead to improved clinical trials, as we will know exactly what features of sleep we need to improve, and at what age or stage of development to target them.

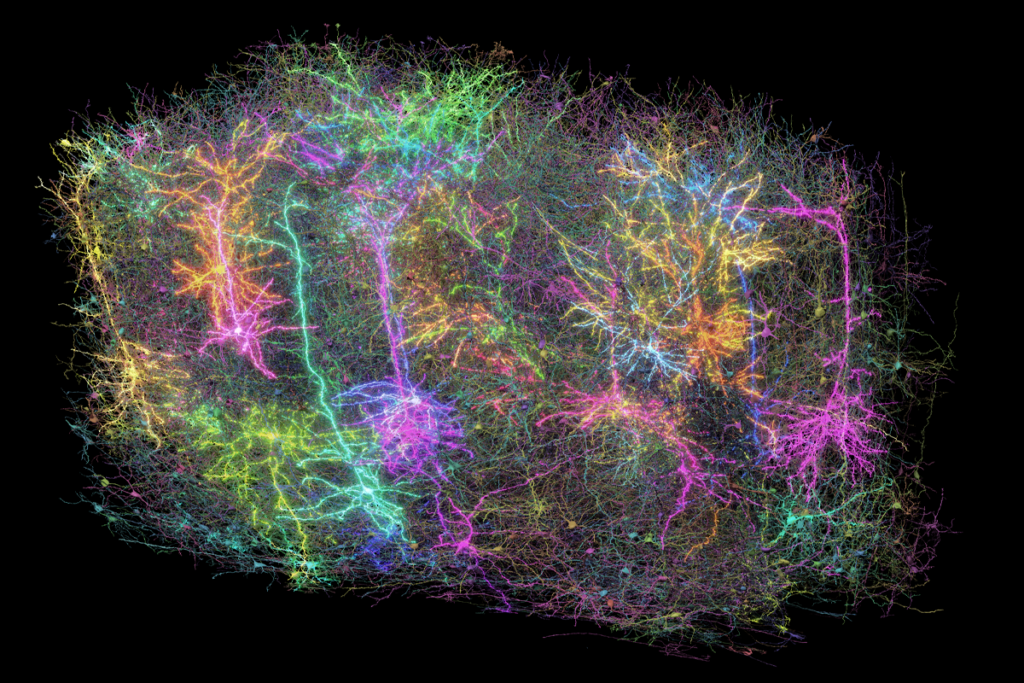

We also need to understand the neurobiological underpinnings of insomnia in these various conditions.

Last year, my colleagues and I identified a pattern of abnormal brain activity in children with dup15q syndrome. In an ongoing study, we have found that this signature persists during sleep, potentially fueling sleep disruptions and interrupting critical processes that unfold during slumber.

Healthier sleep can have a profound domino effect on other areas of functioning. I hope that we can one day effectively treat insomnia in autism in a manner that is informed by the specific genetic cause. I will certainly sleep better when I know that the children I see and their caregivers are all well rested.

Shafali Jeste is associate professor of psychiatry and neurology and the University of California, Los Angeles.

References:

Recommended reading

Split gene therapy delivers promise in mice modeling Dravet syndrome

Changes in autism scores across childhood differ between girls and boys

PTEN problems underscore autism connection to excess brain fluid

Explore more from The Transmitter

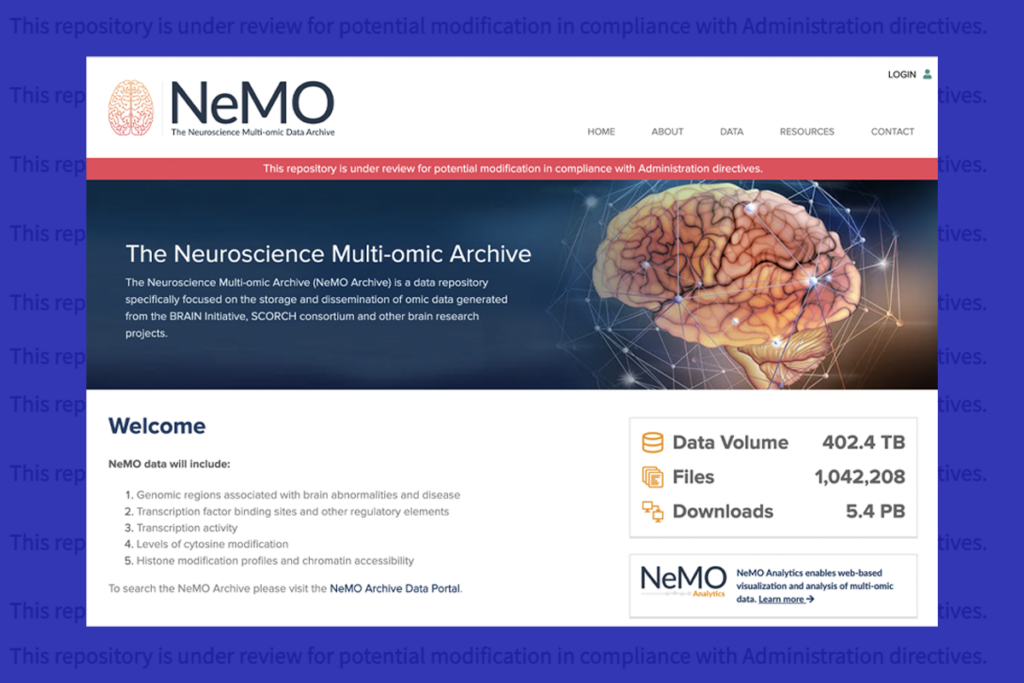

U.S. human data repositories ‘under review’ for gender identity descriptors