Treating Rett syndrome

Treatment with the insulin-like growth factor (IGF) greatly improves the health of mouse models of Rett syndrome ― a regressive genetic disorder that causes mental retardation, seizures, and autistic features ― according to unpublished researched presented this morning at the Society for Neuroscience conference.

Treatment with the insulin-like growth factor (IGF) greatly improves the health of mouse models of Rett syndrome ― a regressive genetic disorder that causes mental retardation, seizures and features of autism ― according to unpublished researched presented this morning at the Society for Neuroscience conference.

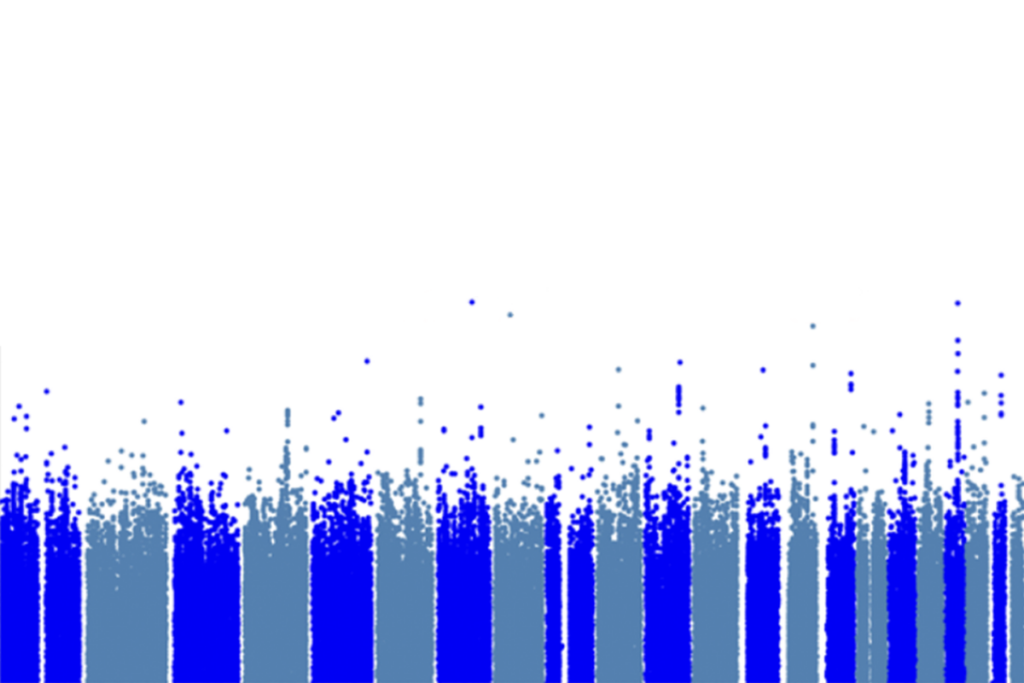

Researchers led by Huda Zoghbi at the Baylor College of Medicine first linked Rett syndrome to mutations in the MeCP2 gene in 1999. Since then, Zoghbi and others have created three different MeCP2-deficient mouse models of the disorder.

In experiments described today, researchers injected MeCP2 knockout mice with a peptide derivative of IGF. The growth factor is known to affect the signaling of another protein, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a known target of the MeCP2 protein.

The IGF treatment led to significant improvements in brain weight, neuron size, gait, nighttime movement and tremors compared with untreated animals, reported Daniela Tropea, a postdoctoral fellow in Mriganka Surʼs laboratory at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The treatment also significantly increased the miceʼs lifespan, although they still lived a shorter time than do healthy mice.

The researchers are seeking funding for clinical trials of IGF in humans. Unlike BDNF, IGF can cross the blood-brain barrier. What’s more, because the drug is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treating children with short stature, clinicians have already worked out optimum dosages, Tropea says.

Although the results are promising, Tropea is careful to note that the treatment did not completely rescue the deficits in the Rett mice. “They were all significant improvements, but we shouldn’t expect a miracle,” she says.

For all reports from the Society for Neuroscience conference, click here.

Explore more from The Transmitter

Remembering Annette Dolphin, who helped explain gabapentin’s effects