Tracking time can be tricky for children with autism

Children with autism have trouble relying on past experiences to gauge how long things typically take.

Children use their sense of time to guess when the school bell will ring, when to pause while chatting with a friend, and how long it typically takes Dad to buy groceries. A good sense of time makes life less unpredictable, and may also smooth out some social interactions.

Most children get better at estimating time as they grow. They learn by averaging their experiences — for instance, previous trips to a supermarket or conversational pauses. Some children have an innate sense of time and rely less on this imprecise averaging tactic.

Children with autism are known to have trouble estimating time. A new study suggests a reason for the problem: their relative inability to rely on past experiences as a guide.

The findings, published 28 June in Scientific Reports, could help to explain why some people with autism have anxiety and social difficulties1.

Researchers at University College London asked 23 children with autism, aged 7 to 14, and 23 age-matched controls to judge the length of intervals between three flashes of a green circle on a screen. The intervals became more similar in length with each round.

The children with autism stopped being able to differentiate between the intervals in earlier rounds than the controls did.

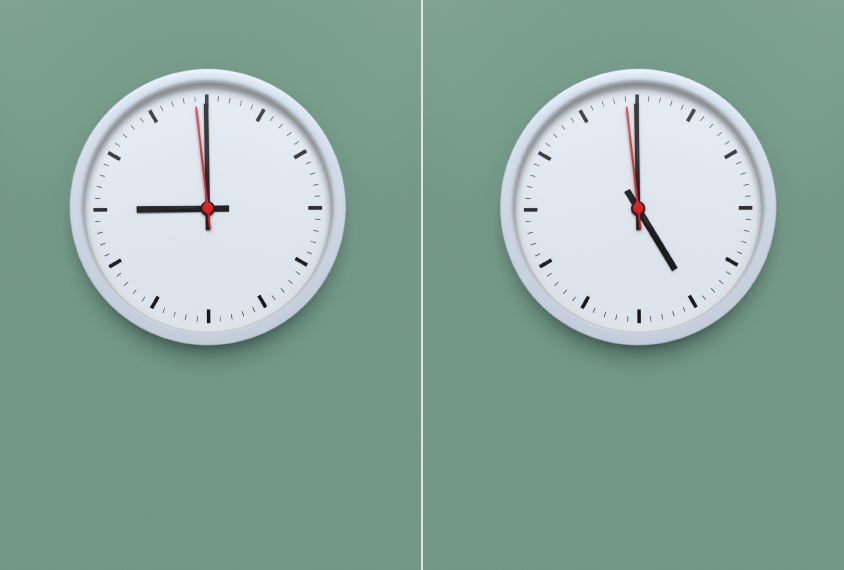

Finding time:

The researchers then asked the children to reproduce the interval between the first two flashes by pressing a button when they predicted a third flash should occur. They repeated this task for varying intervals.

Some of the children estimated the timing of the third flash based on the average of all previous intervals, so they underestimated long intervals and overestimated short ones. The children with autism fell into this category, suggesting they lack an innate sense of time.

The researchers then compared the performance of children who have autism with that of a group of 12 typical 6- and 7-year-olds. Because they are young, these children have relatively poor time perception. Their ability to judge the time intervals was on par with the autism group.

But the children with autism performed worse than the 6- and 7-year-olds at the time prediction task; their estimates were further from the average of the intervals. This suggests that children with autism don’t reliably use their past experiences to gauge time.

They may also have difficulty using prior knowledge to fine-tune sensory signals for sights and sounds, says Themelis Karaminis, who did the work as a postdoctoral researcher in Elizabeth Pellicano’s lab. “Our study situates these difficulties within a more general theory for autistic perception, for how autistic people see the world differently,” Karaminis says.

Trouble with time perception may also make the world seem unpredictable, causing people with autism to become anxious, says Melissa Allman, assistant professor of psychology at Michigan State University, who was not involved in the study. “Somebody with autism may be lost in a sea of time,” she says.

References:

- Karaminis T. et al. Sci. Rep. 6, 28570 (2016) PubMed

Recommended reading

Documenting decades of autism prevalence; and more

Expediting clinical trials for profound autism: Q&A with Matthew State

Explore more from The Transmitter

‘Perturb and record’ optogenetics probe aims precision spotlight at brain structures