‘Tooth Fairy’ works magic to unearth new autism genes

By analyzing stem cells derived from baby teeth, researchers have tracked a child’s autism to mutations in a gene called TRPC6. The molecular saga highlights a painless way to probe the role some genes play in autism.

For some children with autism, the ‘Tooth Fairy’ lives in San Diego and wears a white coat. And the Tooth Fairy may offer an answer to what causes their autism, without painful blood draws or skin biopsies.

Alysson Muotri, associate professor of pediatrics and cellular molecular medicine at the University of California, San Diego, created this inventive project in 2012. He realized that rather than force children to undergo upsetting procedures, parents could simply mail one of their child’s baby teeth, which contain enough genetic information to eliminate the need for an in-person visit.

“We announced the project on social networks like Facebook,” Muorti says. “News spread fast.”

The project has roughly 3,500 registered families and 300 teeth so far, and researchers have found five autism candidate genes from the 20 or so cell lines they have sequenced. Several of those genes have never been implicated in autism before. The researchers described their results with one candidate, TRPC6, in November in Molecular Psychiatry1.

“We’re finding lots of new genes and sometimes we have no idea what they do, so the next step is to test whether or not those genes are important,” Muotri says. “This type of study may reveal novel pathways in autism and open up the possibility for personalized treatment.”

Autism’s cause is clear in a subset of cases, but the majority of cases are sporadic, meaning they arise from an unidentified combination of genetic and environmental factors.

“Every sporadic individual will likely carry several mutations that probably contribute to a certain extent to the disease, so it is really hard to model that complex phenotype,” Muotri says.

Candidate connection:

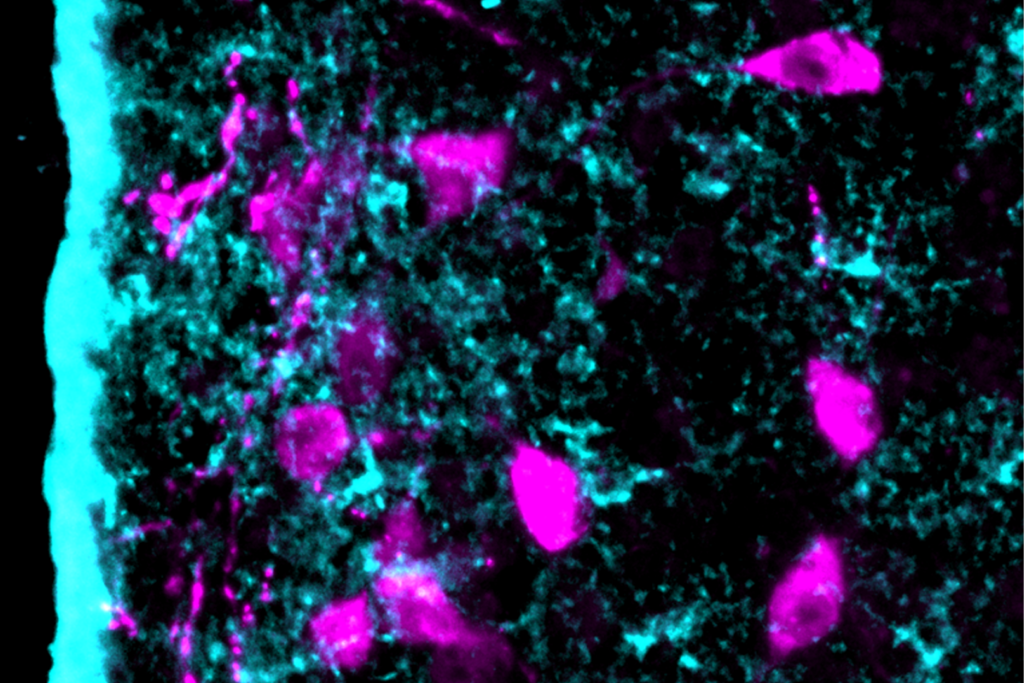

After receiving a tooth, the researchers extract cells from the dental pulp and sequence the whole genome to search for mutations associated with sporadic autism. They then use these dental cells to create induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, which can be coaxed into becoming neurons. Muotri says he and his colleagues are the first to use iPS-cell-derived human neurons to model sporadic autism.

One of the first baby tooth samples came from an 8-year-old boy with autism and a mutation in one copy of the TRPC6 gene, which encodes a calcium channel.

“This gene had never been related to autism before,” says Muotri. “No one was talking about it, and that was exciting to us.”

TRPC6 helps neurons form dendrites — the tiny protrusions that form the receiving ends of neuronal junctions, or synapses. Neurons made from the boy’s dental pulp have fewer dendrites and fewer excitatory synapses than controls neurons do. Eliminating TRPC6 expression from control neurons has a similar effect on dendrites and synapses, which can be reversed with injections of TRPC6.

Muotri and his team also tested the effects of TRPC6 mutations in mice. They found that adult mice with half the normal amount of TRPC6 show some autism-like behaviors, such as heightened anxiety and decreased interest in novel objects compared with controls.

Looking at genetic data from unrelated projects, the researchers found that 10 of 1,041 people with autism have harmful mutations in TRPC6, compared with 4 of 2,872 controls. Two of the people with autism have mutations that cause complete loss of TRPC6 function.

The researchers estimate that TRPC6 mutations in occur in less than 1 percent of people with autism — a frequency on par with that of other autism-associated candidates, such as SHANK3. Interestingly, TRPC6 is activated by MeCP2, which is mutated in the autism-linked disorder Rett syndrome, suggesting some overlap between different forms of autism.

Jack Price, head of the Centre for the Cellular Basis of Behaviour at King’s College London, who was not involved in the study, calls the study “a tour de force” for the clear and thorough way the scientists did their work.

However, it’s unclear how strongly TRPC6 is associated with autism, if at all, Price says: It could be that the boy’s mutation has nothing to do with his developing the disorder.

Hyperforin helper:

Muotri and his team followed up their lab findings with a clinical approach that adds weight to their hypothesis.

They used a drug called hyperforin, the active ingredient in St. John’s wort, a popular alternative medication for depression. Hyperforin induces the influx of calcium into cells by activating TRPC6.

“Since the boy still has one functional copy of TRPC6, we hypothesized that hyperforin could compensate for the loss of function in the other allele,” Muotri says.

With the family’s consent, the boy went off of all medications and took three to four capsules of St. John’s wort per day for one month. During that time, the researchers surveyed the boy’s parents, teachers and a group of psychologists about his behavior.

Although the boy’s mother reported no change, his father said he seemed more social. His teachers and the psychologists reported that the boy was more focused and less anxious.

“This is a groundbreaking study that needs replication but advances translational science in autism in a number of distinct ways,” says John Constantino, director of the Intellectual and Developmental Disability Research Center at Washington University in St. Louis, who was not involved in the study. He says TRPC6 should be studied further to see what role it might play in autism.

Muotri says the study’s results provide anecdotal evidence that hyperforin may improve behavior in children with autism and TRPC6 mutations.His team plans to explore the drug’s effects in mice.

“There are definitely no drugs out there that can treat the core symptoms of autism,” Muotri says. “But St. John’s wort is a natural product, and it could offer an opportunity for a therapeutic approach.”

References:

1. Griesi-Oliveira K. et al. Mol. Psychiatry Epub ahead of print(2014) PubMed

Recommended reading

New autism committee positions itself as science-backed alternative to government group

Astrocytes orchestrate oxytocin’s social effects in mice

Explore more from The Transmitter

Securing the academic pipeline amid uncertain U.S. funding climate

Let’s teach neuroscientists how to be thoughtful and fair reviewers