To test or not to test

A new survey reveals how parents feel about genetically testing their children for untreatable diseases.

Here’s a hypothetical question for any parent of a young child: Would you give your child a genetic test for a disease with an uncertain onset age, mild symptoms and no treatment? How about a test for a condition that leads to severe disability?

A report published last week in Pediatrics was the first to ask parents about their genetic testing preferences in a statistically rigorous way. Tallying 1,342 responses, the survey found that when asked about untreatable diseases, about one-third of parents are definitely or probably interested in testing, one-third are definitely not or probably not interested, and one-third are unsure. Those numbers stayed consistent regardless of the severity of the disease in question.

The findings are quite surprising given current ethical standards. Most doctors and genetic counselors only endorse testing for diseases that have proven treatments, or treatments that have shown promise in clinical trials. For instance, babies are routinely tested for phenylketonuria, a deadly metabolic disease that can be prevented by a specific diet.

Autism has no clinically proven treatments, but several therapies may improve symptoms in some kids. For that reason, I would argue that forgoing testing might actually harm the child in the long run.

If a genetic test identifies a known autism risk factor in a 1-year-old, for instance, that might spur the parents to look for warning signs of the disorder, and perhaps begin early intervention programs.

It looks like at least one-third of parents would agree with me. With the current rise of home DNA tests, it may not be long before eager parents bypass the genetic counselors — and the ethical status quo — and take matters into their own hands.

Recommended reading

PTEN problems underscore autism connection to excess brain fluid

Autism traits, mental health conditions interact in sex-dependent ways in early development

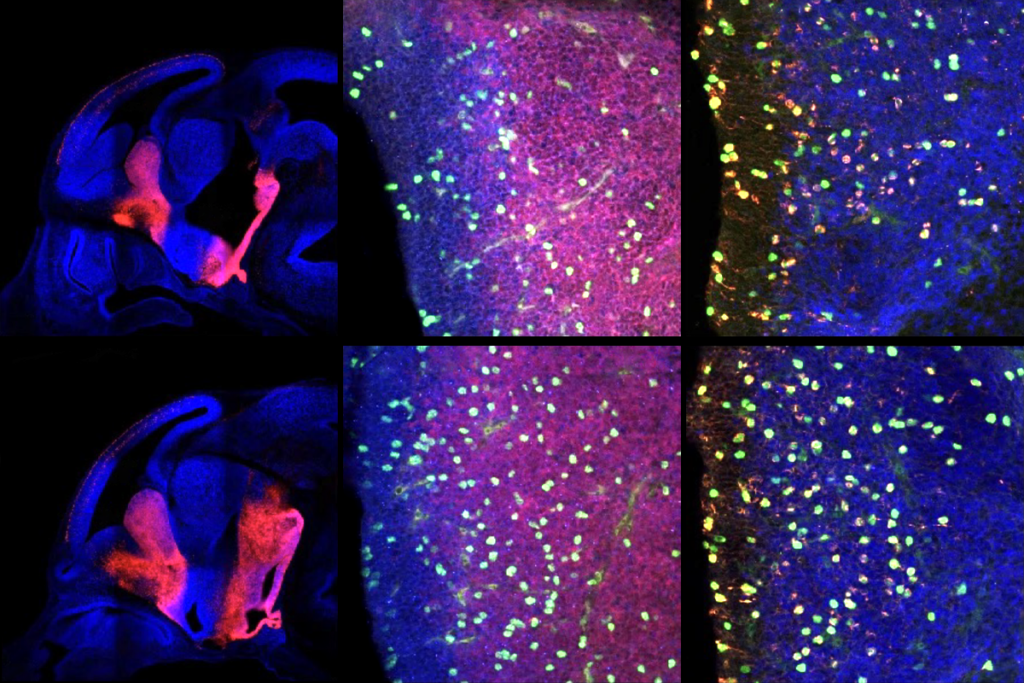

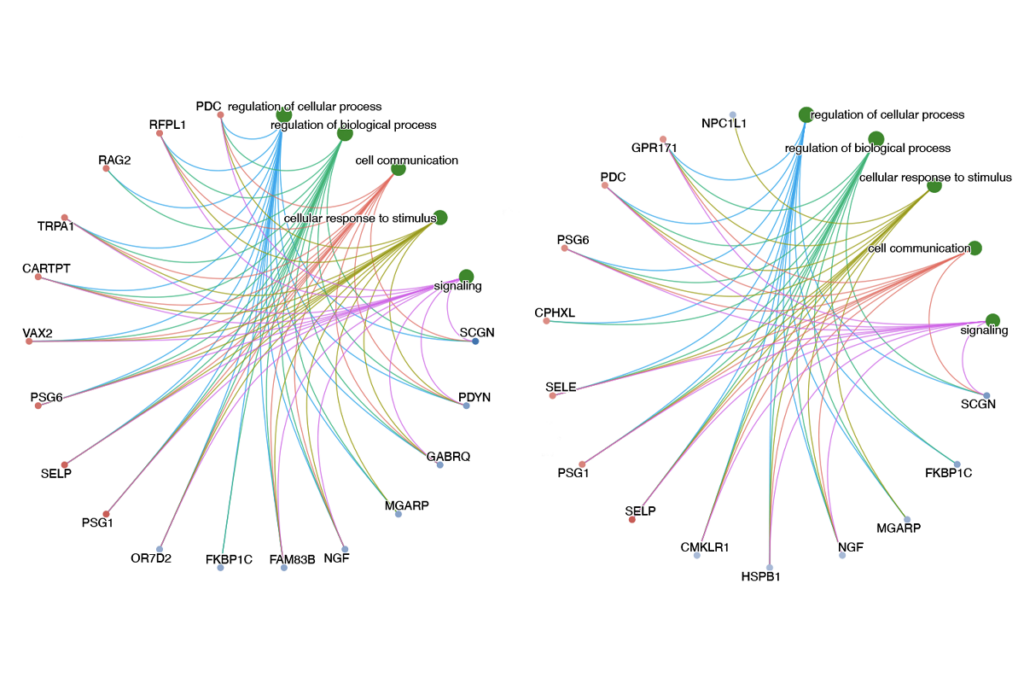

New tool may help untangle downstream effects of autism-linked genes

Explore more from The Transmitter

Newly awarded NIH grants for neuroscience lag 77 percent behind previous nine-year average