Prenatal vitamins help ensure that a fetus has everything it needs to develop. Research indicates that too little — or too much — of certain substances during pregnancy can increase the child’s chances of having autism.

But many of these studies are observational in nature and are not set up to prove a cause-and-effect relationship. In some cases, unrelated lifestyle factors — such as frequent hand-washing, eating a generally healthy diet, or other behaviors that are potentially more common among people who are thoughtful about prenatal nutrient intake — may explain an apparent link between prenatal nutrition and autism.

Here we explain what scientists know about the link between vitamin exposure, prenatal nutritional supplements and autism.

What is the connection between vitamin D and autism?

Vitamin D is the nutrient whose connection to autism may be the most thoroughly studied. The relationship is modest, though, and the evidence only observational; it would be unethical to conduct clinical trials in which developing fetuses were deprived of vitamin D.

Giving pregnant women a low dose of halibut liver oil, which is rich in vitamin D, is linked to decreased rates of preeclampsia and preterm birth, according to a study conducted in London, England in the late 1930s. Both preeclampsia and preterm birth are linked to higher odds of autism.

More recent research, too, shows that having low levels of vitamin D during pregnancy is associated with a higher likelihood of having a child with autism. Women with low blood levels of vitamin D during pregnancy, for example, were more than twice as likely to have a child with autism as those who were not vitamin D-deficient, according to one analysis in the Netherlands. But autism is relatively uncommon in this population — with a prevalence of 1.6 percent — so doubling the chances still represents only a small absolute increase over the 1.4 percent prevalence seen in the general population. Most of the women with low vitamin D did not have children with autism.

In the Dutch study, only low vitamin D levels during the second trimester were linked to autism odds. But vitamin D in the third trimester might also matter: Newborns with low blood levels of vitamin D were 33 percent more likely to later be diagnosed with autism than those born with high blood levels of vitamin D, according to a small study in Sweden.

Supplementing a woman’s diet with vitamin D later in pregnancy does not seem to confer any benefit, though. Children whose mothers take high doses of vitamin D during the third trimester do not have a significantly different neurodevelopmental outcome early in life from that of controls, according to a randomized clinical trial.

Sunlight exposure enables the body to produce vitamin D, so some research has focused on autism prevalence among babies conceived during winter months, when there is less sunlight during the day. In one study in Scotland, 1.3 percent more children conceived during winter months had autism, intellectual disability or learning difficulties than did those conceived in sunnier seasons.

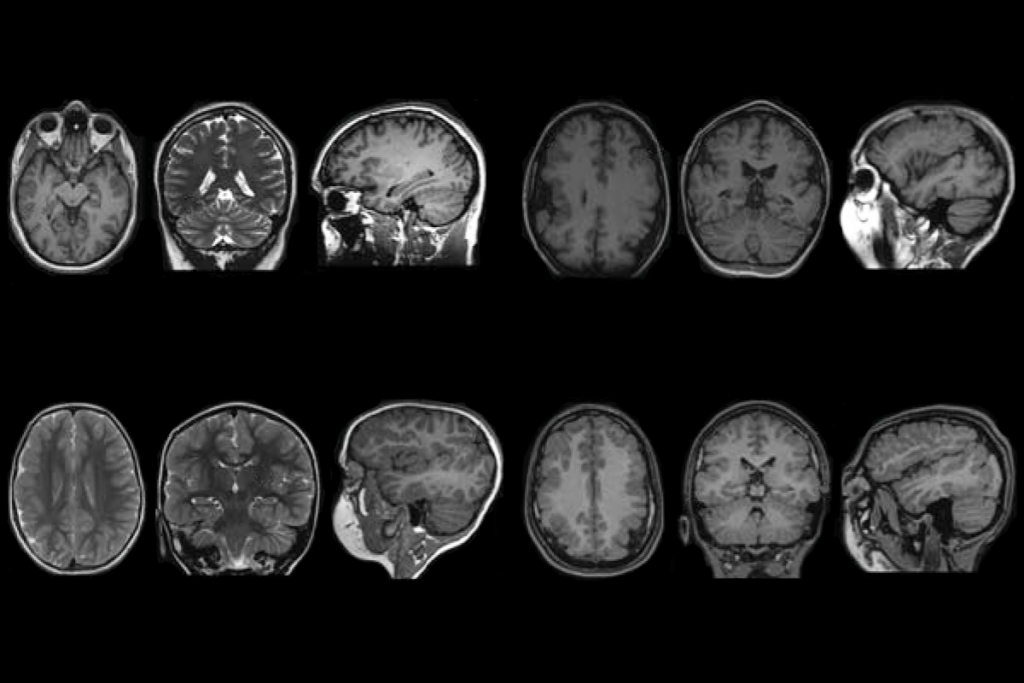

Some experts propose that the increased autism odds among children conceived during winter months are linked to the influenza season. Infections in pregnant women can lead to ‘maternal immune activation,’ which, among other things, may speed up the expression of autism-linked genes.

What about folate?

Folic acid is the synthetic form of folate, a B vitamin, and is found in many prenatal supplements and fortified foods, such as cereals and pastas. It is crucial for cell proliferation, which is in overdrive during pregnancy. Insufficient folate during fetal development has long been linked to neural tube defects, such as spina bifida and anencephaly.

Multiple studies link prenatal folic acid supplementation to lowered odds of autism, even when pregnant women take epilepsy medications, such as valproic acid, that appear to increase those chances.

Too much folic acid may also increase the odds of autism, though. Excess folic acid supplementation had similar effects as folic acid deficiency in one mouse study, for example. The experimental mice in this study ingested 10 times as much folic acid as controls. These results do not mean folic acid should be avoided — just that it should be taken in recommended quantities.

Is there evidence linking iron supplements with autism?

This mineral is an essential component of the protein hemoglobin, which enables the blood to carry oxygen around the body and to a fetus’ developing brain.

Anemia, or iron deficiency, during pregnancy is linked to increased odds of autism, intellectual disability and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children.

Iron may also offset any negative effects from maternal immune activation by protecting against a class of immune molecules called C-reactive proteins.

Are there other nutritional factors at play — maybe fatty acids?

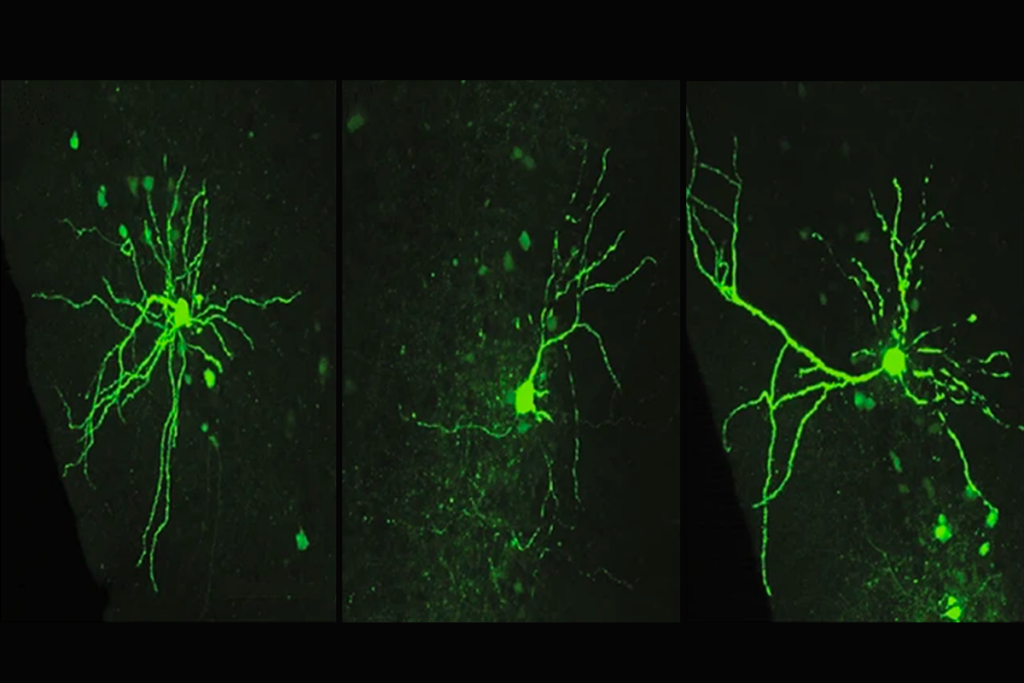

Fatty acids reinforce cell membranes and ensure proper communication between neurons.

Some parents of autistic children swear by fish oil supplements to help ease behavioral issues, but the research is spotty.

Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), an omega-3 fatty acid found in oily fish, may offset the effects of maternal malnutrition or stress, both of which can alter gene expression and contribute to autism odds, according to a mouse study.

Other fats may not have the same protective effects. A high-fat diet during pregnancy can lead to persistent, potentially harmful brain changes in mouse pups, according to one study. Some of the brain areas affected in this study include behavioral circuits associated with autism.

What do you even do with this information?

Half of pregnancies are unplanned, and in the case of some nutrients, such as folate, it is protective only if it’s taken right before and just after conception. When it’s best to take vitamin D is unclear, as is true for most other nutrients.

Additionally, many studies on prenatal nutrition contain a multitude of confounding or unmeasured variables. Scientists usually do everything they can to eliminate the impact of any confounding factor, such as maternal exercise, access to healthcare or a genetic predisposition, but it is not possible to eliminate every possibility. So any observational study on maternal nutrition and its link to autism comes with a big caveat: It cannot prove cause and effect.

Overall, there may be a non-causal association between prenatal vitamins and their protective effects. Research shows vitamins confer many benefits even when women take them for up to two years before getting pregnant: Women who take vitamins may be health-conscious in other ways.

Consulting with a physician is always best for each individual.