The blurred line between autism and intellectual disability

Doctors often conflate autism and intellectual disability, and no wonder: The biological distinction between them is murky. Scientific progress depends on knowing where the conditions intersect — and part ways.

S

oon after Patrick Kelly started school at age 5, his teachers told his parents he belonged in special-education classes. His academic performance was poor, and his behaviors were disruptive: hand-flapping, rocking, hitting his head with his wrists and tapping his desk repeatedly. He often seemed as if he was not paying attention to people when they spoke to him. He would stare off into the distance, head turned to the side.Kelly’s teachers assumed he had intellectual disability, known at the time as mental retardation. Then when he was around 9, a routine eye exam at school revealed that he could barely see. With glasses, he went from underperforming to outperforming his peers in every subject but English in just two years. And it turned out that he had been listening in the classroom (and to his parents talk about him) all along. Finally, at age 13, a psychologist diagnosed him with pervasive developmental disorder-not otherwise specified, a form of autism.

Now 29 and a college graduate, Kelly works in Malone, New York, as a direct-support professional, helping people with autism, intellectual disability and related conditions learn how to do basic tasks such as shopping, along with communication skills. In his work, he says, he frequently encounters stories like his own — autistic people who were erroneously thought to have intellectual disability. “I have seen way too many cases of people with [autism] who, after resolving a confounding issue, start to do really well,” he says. “We’re weird, there’s no denying that. But there’s a difference between being different and straight up not understanding things.”

The medical establishment once considered autism and intellectual disability to be virtually inseparable. In the 1980s, as much as 69 percent of people with an autism diagnosis also had a diagnosis of mental retardation. By 2014, the figure for a dual diagnosis — with mental retardation now called intellectual disability — had declined to 30 percent, as researchers had sharpened the diagnostic criteria for autism.

These figures are fluid, however, because the line between autism and intellectual disability remains fuzzy: Doctors often mistake one condition for the other or diagnose just one of the two when both are present. Genetic overlap further blurs the picture. Most genes identified as autism genes also cause intellectual disability. And researchers face roadblocks to progress in making the demarcation, including a funding imbalance that favors autism research and the fact that it is often easier to study autistic people without intellectual disability than with it.

Overcoming those challenges would have widespread implications. In the lab, illuminating the biological distinctions between autism and intellectual disability could lead to new insights into the causes of each condition. It could transform research by enabling researchers to accurately document the diagnoses of participants in their studies. “What’s at stake is the state of our science,” says Somer Bishop, a clinical psychologist at the University of California, San Francisco. “I think that if we lose all the specificity of what makes each [condition] unique in its own right, then we’re slowing down discovery.”

In the clinic, clearer diagnoses would guide a large number of people into the services most appropriate for them. “We have to figure out who has only autism, who has only intellectual disability and, importantly, who has both intellectual disability and autism,” says Audrey Thurm, a child clinical psychologist at the National Institute of Mental Health in Bethesda, Maryland. “That’s millions of people who could be better served by having an accurate distinction that would put them in the right group and get them the right services.”

Major concern:

A

s of 2014, schools in the United States included about 600,000 children with a primary diagnosis of autism and 400,000 diagnosed with intellectual disability, according to the U.S. Department of Education. But those numbers are only as accurate as the diagnoses. And untangling the two conditions has been a challenge ever since autism was first described in the 1940s. “Differentiating autism from intellectual disability is as old as the condition,” Thurm says. “It was a major concern, right from the beginning.”Intellectual disability is characterized by difficulties in reasoning, problem-solving, comprehending complex ideas, and other cognitive skills; its diagnosis is based on an intelligence quotient (IQ) of 70 or less. Autism, on the other hand, is defined primarily by social difficulties, communication issues and repetitive behaviors. Yet intellectual disability comes with a suite of developmental delays that can include social differences, and that can lead clinicians astray. It makes sense for clinicians to diagnose someone with autism only if the social differences are greater than expected for the person’s developmental level, Bishop says. She saw one teenage boy with an IQ of 50 who was struggling socially in a mainstream high school. He had scored high on an autism screen as part of a research project. But because his social skills matched his developmental age of about 7 years, a diagnosis of autism was not appropriate. And yet Bishop was the first clinician to tell his mother that he had intellectual disability.

Bishop was also the first to diagnose a 7-year-old girl with intellectual disability who came to her clinic. The girl was in a wheelchair, barely tracked objects with her eyes and was unable to speak or engage socially. Her developmental delays put her on par with an infant, too young to test for autism. And still, a neurologist had referred the girl to an autism clinic, in part because her parents had read about services that help nonverbal autistic children learn to talk.

Rigorous testing for intellectual disability is far from universal, however: Though it is considered best practice, clinicians do not always give people an IQ test in the context of an autism evaluation, which means that many cases of intellectual disability go undetected, says Catherine Lord, a clinical psychologist at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Bias among parents and clinicians also limits the number of intellectual disability diagnoses. Parents may seek an autism diagnosis because services are often easier to access for that condition than for intellectual disability — or require an autism diagnosis to access at all. Clinicians know what kinds of doors an autism diagnosis opens and so may err on the side of autism, too, particularly if they are not sure, Bishop says. They may find it difficult to take that option off the table. “It’s just a terrible thing to ask a clinician to draw a hard line and say, ‘This can’t be autism,’” she says. “Then that kid may not get what they need.”

A diagnosis of intellectual disability also may carry even more stigma than autism does. People with intellectual disability face discrimination in access to housing, employment and other realms. Social exclusion can be more extreme for people with intellectual disability than it is for autistic people, who tend to have larger, more organized support groups. And many people believe that intellectual disability is fixed and immutable. (In fact, people with intellectual disability often improve with the standard autism therapy, applied behavior analysis.)

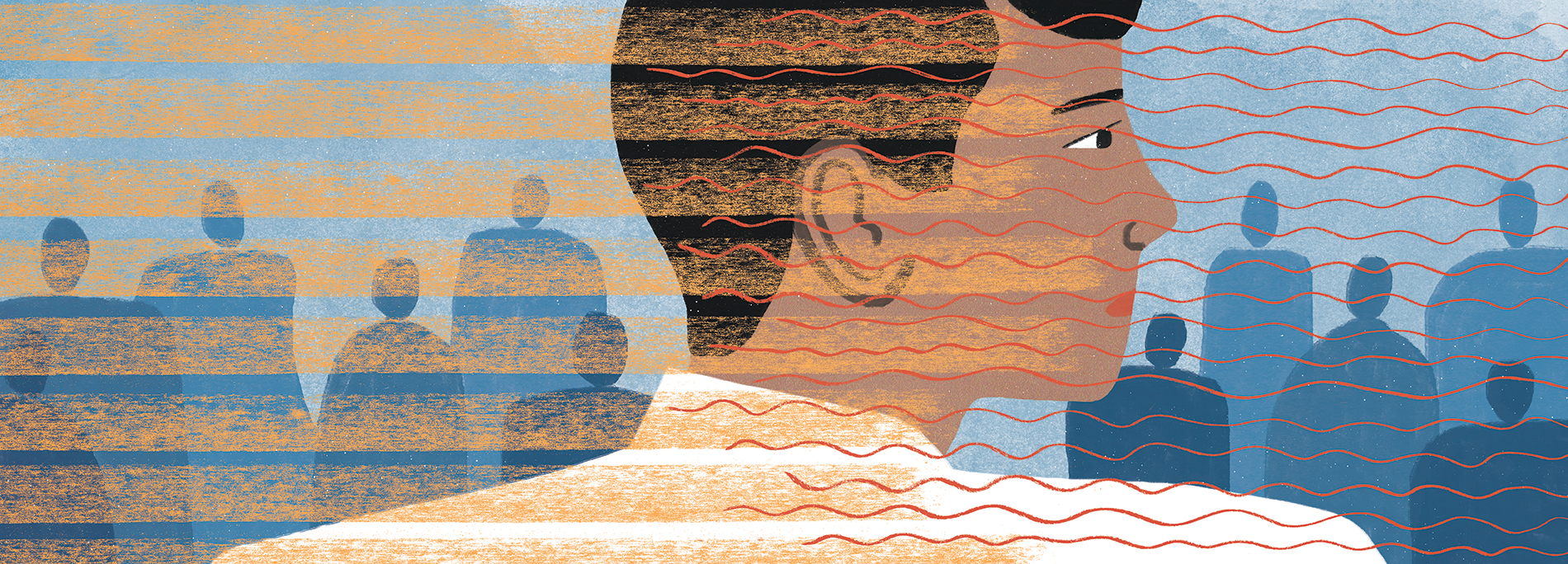

Then there are people like Kelly, who have autism but are incorrectly flagged as having intellectual disability. That kind of mixup, according to a 2009 study, happens disproportionally among children from racial and ethnic minority groups. When clinicians identify intellectual disability in nonwhite children, the researchers found, they are more likely to stop looking for other problems than they are with white children. Intellectual disability may be overestimated in autistic people who speak few or no words as well, says Vanessa Bal, a clinical psychologist at Rutgers University in Piscataway, New Jersey. About 30 percent of school-aged children with autism are minimally verbal, and people tend to make incorrect assumptions about the intelligence of these children. In 2016, Bal and her colleagues reported that about half of minimally verbal children with autism have a nonverbal IQ higher than expected based on their communication difficulties.

Kelly says false assumptions about intelligence may be a huge part of the problem when intellectual disability is erroneously diagnosed in autistic people. These assumptions, he says, often stem from an over-reliance on language and restrictive norms about behavior. His theory has scientific support. In a 2007 study of 38 autistic children, researchers found that scores were an average of 30 percentile points higher on a nonverbal intelligence test than on a test for people with typical verbal skills. In some cases, the gap was as large as 70 points.

Meanwhile, autism can be tough to identify in people with intellectual disability. In a 2019 review of research, Thurm and her colleagues pointed out that two standard autism diagnostic tools — the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) and the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised — have not been validated for people who have severe to profound intellectual disability.

Given the clinical challenges, Bishop says, it is possible that some people included in autism studies and databases have intellectual disability, not autism. “We’re trying to learn more about [autism] and really want to know how to help people,” Bishop says. “When you’ve got huge samples that are sort of polluted by kids who really don’t meet the criteria, it makes it difficult to know what’s what.”

Genetic crossroads:

S

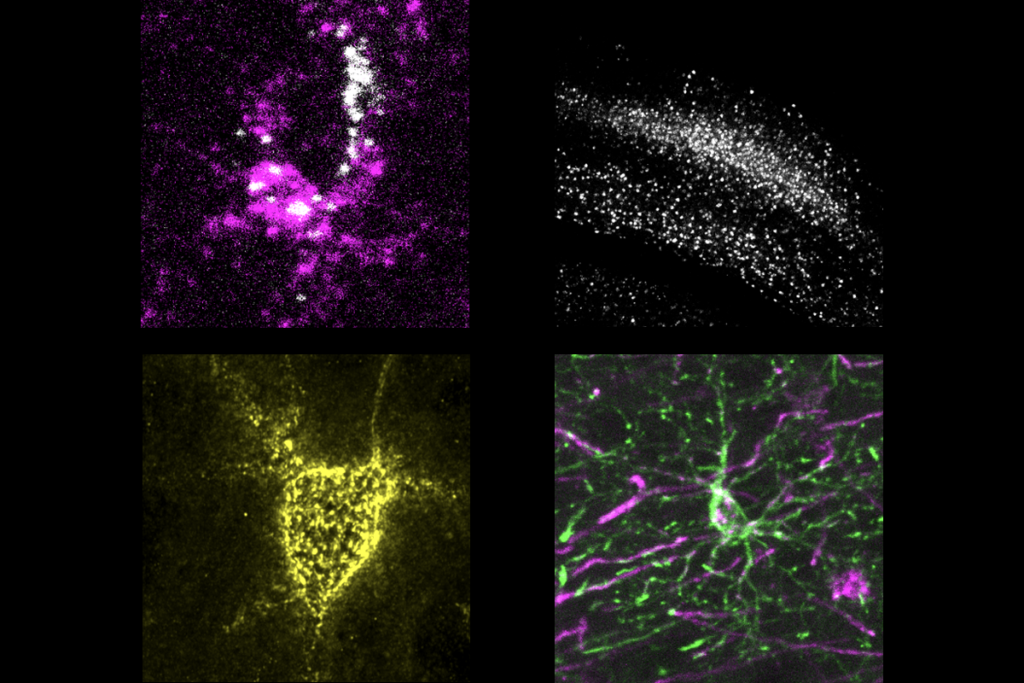

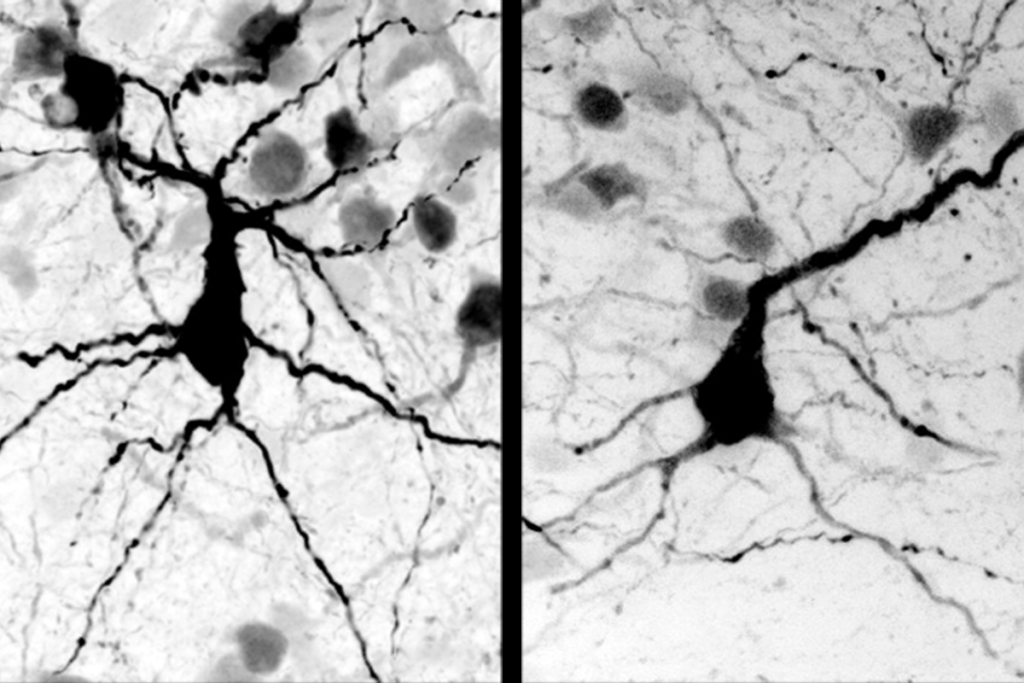

o far, a clear sense of what’s what has not shown up at the genetic level either. Many, if not most, of the top autism genes are also implicated in intellectual disability. To try to sort out which genes are primarily associated with each condition, a team of researchers dove into data collected from more than 35,000 people from multiple databases, including the Autism Sequencing Consortium and the UK10K Consortium, which aims to sequence nearly 10,000 whole genomes.Using these data, the team categorized about half of the 102 top autism genes as slightly more common in autism. The other half were slightly more common in developmental delay, a category that includes intellectual disability. But the work, which was published in February, suggests substantial genetic overlap between the conditions. “This is the first time we were able to quantify it so well,” says lead investigator Stephan Sanders, a geneticist at the University of California, San Francisco. “At a genetic level, the cohort with autism and the cohort with developmental delay share many of the same genes.” In fact, there is doubt that any of the so-called ‘autism genes’ are specific to autism. In a 2020 review of the literature, researchers looked at efforts to identify rare autism mutations and did not find a single gene that increases the chances of autism without also raising the odds of intellectual disability or a related condition.

This overlap is perhaps most obvious in certain rare syndromes in which autism and intellectual disability are inextricably commingled, both genetically and clinically. For example, Phelan-McDermid syndrome usually stems from a mutation in a gene called SHANK3 and is strongly associated with both intellectual disability and autism. Studies suggest that mutations in the gene occur in about 1.7 percent of people with intellectual disability, 0.5 percent of people with autism alone and up to 2 percent of people with autism who also have moderate to profound intellectual disability. Up to 90 percent of people with Phelan-McDermid syndrome are diagnosed with autism.

Fragile X syndrome plays out in a similar way. The condition typically stems from a large number of repeats in the FMR1 gene and shows substantial overlap with autism. Here, too, no one has clearly separated the role of the mutation in intellectual disability from its contribution to autism. “If we’re going to understand how these genes affect neurodevelopment, we need to understand how much the genes are causing intellectual disability versus how specific the deficits are to autism,” Thurm says.

Still, autism researchers mostly tend to avoid distinguishing between the two conditions. Instead, they simply exclude people diagnosed with both intellectual disability and autism from autism studies. A 2019 analysis, for example, showed that across 301 studies of autism, only 6 percent of participants had intellectual disability, compared with 30 percent in the autistic population overall.

Logistical challenges explain some of the neglect, experts say. People with intellectual disability tend to have behavior problems and communication difficulties that can make it hard for them to sit through blood draws, brain scans and other medical procedures. Adults with limited verbal abilities or an incomplete understanding of research practices may not be able to reliably consent to research studies. Researchers also may deliberately study a narrow group of people to avoid complications in the data.

Money likely plays a role, too. Overall, funding is more plentiful for autism than for intellectual disability, Bishop says, and there are fewer and less vocal advocates for the latter condition. As a result, researchers who study rare conditions such as Angelman syndrome and Phelan-McDermid syndrome emphasize the implications for autism and pay less attention to the pronounced intellectual disability people with these conditions show. In genetic studies, relevant genes are flagged as autism genes. “All these kids with various types of [intellectual disability] diagnoses deserve attention,” Bishop says.

Path to clarity:

T

o clearly separate autism from intellectual disability, what is needed first are better diagnostic measurements. “I think we’re missing a lot of opportunities to really help people because we end up using these measures that sort of often just say, ‘Oh, look, this person is really impaired,’” Bal says. “Measurement is a focus to try to understand the nuances.”To grasp that nuance, one team is developing and testing a version of the ADOS that provides more accurate autism diagnoses in minimally verbal adults. Another team is assessing an iPad-based tool for measuring cognitive abilities in people with communication difficulties, an adapted version of a standard cognitive assessment. The new version includes more instructions and provides more practice questions than the standard test, among other adjustments. The team tested the battery on 242 children and young adults with fragile X syndrome, Down syndrome or other forms of intellectual disability — and found that it provides valid results in more than 80 percent of participants with a mental age of at least 4.

Also in development are techniques that assess cognitive function in people with profound intellectual disability by tracking their gaze: Instead of pointing at answers on a tablet, people would answer questions with their eyes. The procedure could allow for testing of cognitive abilities in people who have limited motor skills as well as trouble speaking. Various types of mobile brain scanners, including a modified bike helmet, and specialized head molds also enable researchers to measure brain activity in people with intellectual disability who have trouble staying still.

On the genetics side, Sanders says his team’s findings are a starting point for understanding the biology of the two conditions, which could eventually lead to treatments. For example, a mutation in one gene might confer a large shift in sociability and a small shift in cognitive abilities; another might do the reverse. Researchers could then study each mutation in animal models and stem cells. “There are quite a lot of people who meet the diagnostic threshold for autism and have a normal IQ. And there are people who have reduced cognition, but they didn’t have impairments in sociability,” Sanders says. “If ever we want to try and start developing things which might help those individuals, we need to understand this distinction.”

Families could directly benefit from clarity, says Tina Hyser, a family-care physician in Eagan, Minnesota, whose 11-year-son, Will, began showing developmental delays by his first birthday. Hyser and her husband Andy first sought an autism evaluation for Will when he was 3. At that time, the boy spoke only in two-word phrases, if at all. He was also behind on motor skills; he could not easily climb the stairs to a slide and ride down, as most 3-year-olds can. And his tantrums were extreme. But the family lived in a rural area of Wisconsin then, and testing was not comprehensive.

At age 5, Will received an autism diagnosis. And finally, at age 9 and living near Minneapolis, Minnesota, he underwent a thorough evaluation and was diagnosed with both autism and intellectual disability. He receives in-home services now, but the Hysers still are often unsure how best to support him. Will’s autism is not necessarily typical: He makes eye contact and is interested in social interaction. Many of his meltdowns, Andy says, come from his inability to grasp the concept of time. A better understanding of the connections between cognition and emotion could help the family make decisions about how to care for Will. “I wish we could tease out more and understand better what part of it is autism” and what part is intellectual disability, Tina says. “I really hope we can learn how to support kids like him better.”

Kelly says a better grasp of that dichotomy might also help neurotypical people understand autistic people like him. For example, Kelly says, he may sometimes stop talking in a public place because he feels overwhelmed — not because he has nothing to say. And when he averts his eyes in a conversation, it is because he finds eye contact uncomfortable, not because he is not listening or understanding.

In his view, autistic people see intelligence as separate from social skills, whereas neurotypical people often see these traits as intertwined. The tendency to assume intellectual disability in people with autism arises from that misunderstanding, one that could partly be resolved through better communication, he says. “I think there’s a huge disconnect between how the two groups are seeing this, and nowhere near enough people actually talking to us.”

Recommended reading

Explore more from The Transmitter

Neuro’s ark: How goats can model neurodegeneration