T

he first time Autumn Van Kirk noticed a computer was in her kindergarten classroom — it was an Apple 2, and she could not keep her hands off it. “I was playing with it one day. I was, like, ‘Hey, check this out. There’s little knobs and buttons and stuff. What do these do?’” The teacher ran over and said, “What are you doing? You can’t touch that!” Van Kirk recalls. Her parents got a talking to as well. But it would have taken a lot more than that to discourage Van Kirk’s interest in technology. She built a computer from stray parts when she was 13 or 14, and in college, she programmed a website that she ran from a server in her closet. Today she is a team leader for a top global tech company in Houston, Texas.Van Kirk, 38, has leveraged one of the hallmarks of autism, an intense and often narrow focus on a specific topic, into a career. She is not alone. Livestock industry consultant Temple Grandin and automobile restorer John Elder Robison are famous for turning their special interests into careers. And in response to a 2020 Twitter post by autistic blogger Pete Wharmby — “Anyone #autistic managed to make a living from a special interest?” — dozens of people responded that their passions had led to jobs as diverse as librarian, TV producer, tattoo artist, train conductor and paleontologist.

But it’s only in the past decade or so that autism professionals have begun to recognize the value of these intense interests that emerge in early childhood. Clinicians have historically called them circumscribed interests, and they belong to the category of diagnostic criteria for autism called “restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests or activities,” which also includes movements such as hand-flapping and an insistence on rigid routines. A distinguishing aspect of special interests is their intensity: They can be so absorbing that they are the only thing the person wants to do or talk about.

These interests are extremely common among people with autism: 75 to 95 percent have them. An interest may involve collecting items such as postcards or dolls, listening to or playing music in a repetitive way, or focusing intensely on a narrow topic, such as insects fighting. Special-interest topics may be commonplace — things such as trains, gardening or animals — but people on the spectrum sometimes gravitate toward more quirky fascinations such as toilet brushes, tsunamis or office supplies.

Whatever the subject, interests may hijack family life, and children may throw tantrums when parents try to redirect them. The sister of one autistic man complained in a 2000 study that his interest in maps “swallow[s] up everything, all the time. We can’t talk about anything else.” Teachers and therapists frequently discourage interests out of a belief that they distract from schoolwork and make it harder to fit in with peers.

But research conducted over the past 15 years is revealing what many people with autism have long known — namely, that special interests are valuable to people on the spectrum. In addition to occasionally launching a career, they reliably build self-confidence and help people cope with emotions. Studies also suggest they can help autistic children gain social skills and learn.

This research is also changing the scientific understanding of what special interests are. Experts used to consider them an avoidance activity, something autistic people did to manage negative emotions such as anxiety. But increasingly, studies reveal that these interests are intrinsically rewarding. “There’s been a lot of negative language used around special interests, things like ‘inflexible’ and ‘obsessions,’” says psychologist Rachel Grove, a research fellow at the University of Technology Sydney in Australia. “The real paradigm shift is thinking about special interests as more positive.”

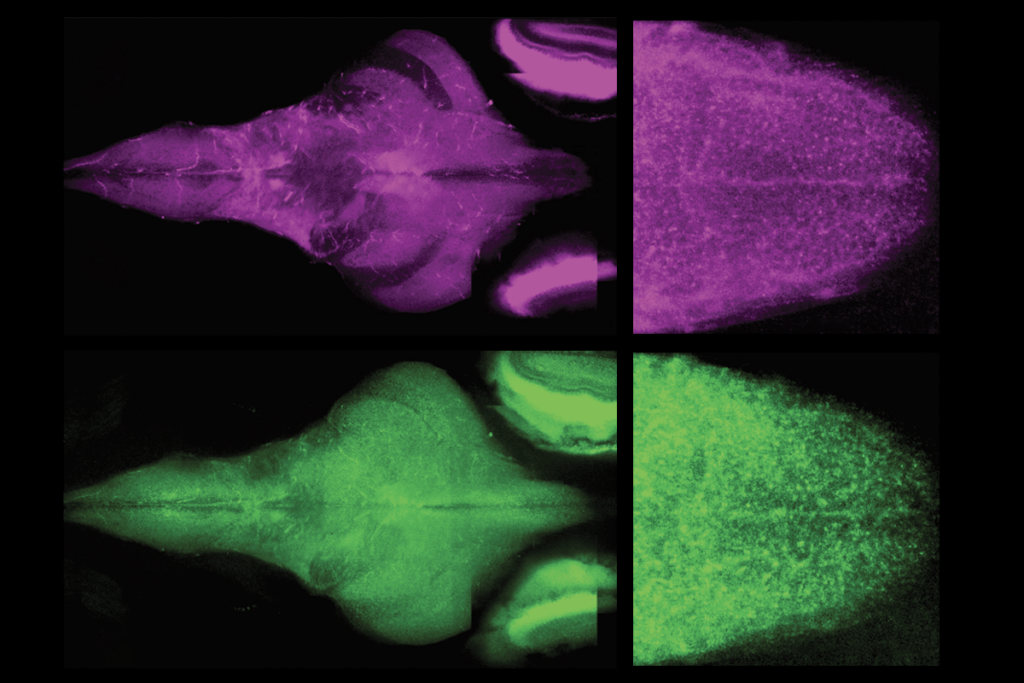

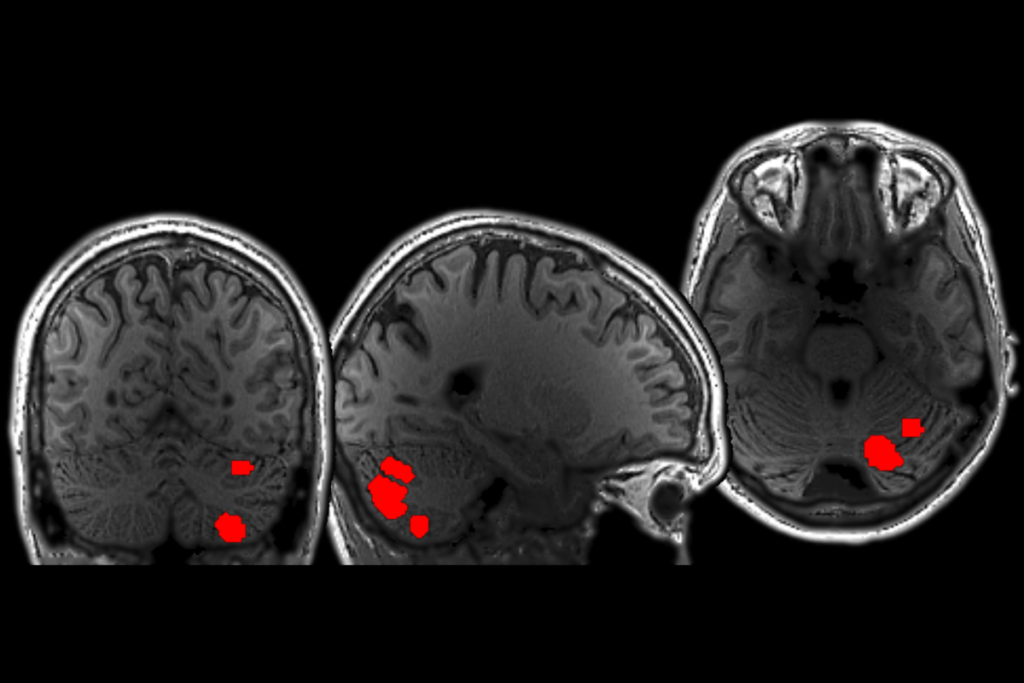

Instead of trying to erase or squelch special interests, teachers and clinicians are starting to leverage them. Educators are working them into the curriculum. Psychologists are finding ways to mitigate the problematic behaviors associated with interests without discouraging the interests themselves. And neuroscientists are beginning to probe how the brain processes special interests, to better understand the neural circuitry involved.

Special interests can dramatically improve children’s life skills, as journalist Ron Suskind revealed in his 2016 documentary, “Life, Animated,” about how his son Owen’s passion for Disney movies helped him learn to speak. Experts hope that the research on interests will help many more children who can be otherwise hard to reach. “Sometimes you hear this phrase, ‘To meet the child where the child is,’” says neuroscientist John Gabrieli of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “If this is their natural motivating capacity, then rather than try to suppress it, it might be more helpful to the child to build on it.”