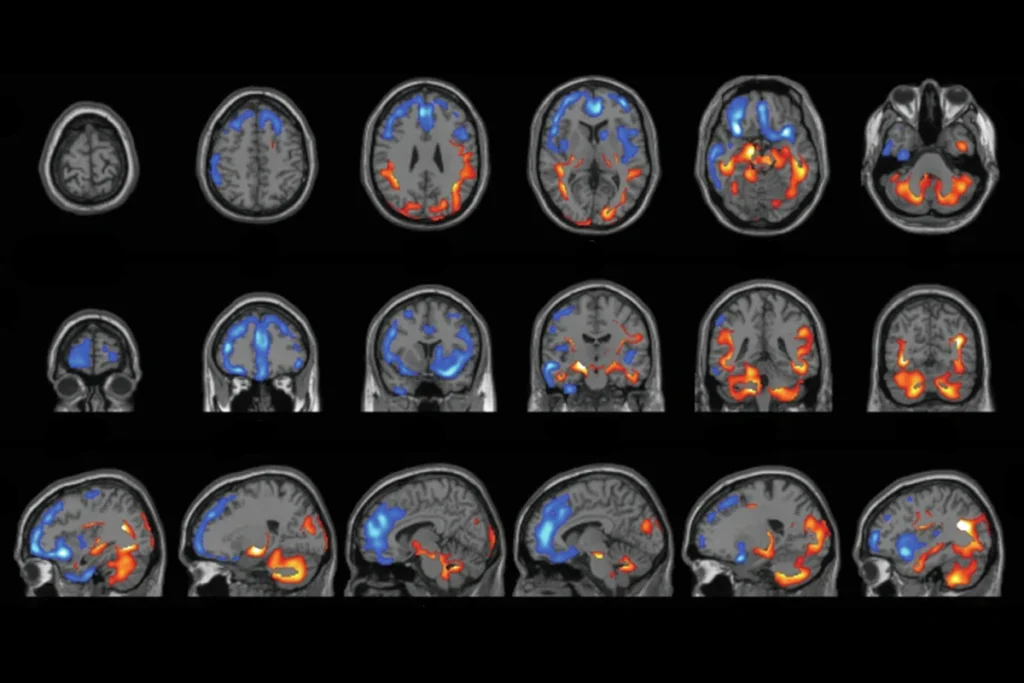

Synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus involves both strengthening relevant connections and weakening irrelevant ones. That sapping of synaptic links, called long-term depression (LTD), can occur through two distinct routes: the activity of either NMDA receptors or metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs).

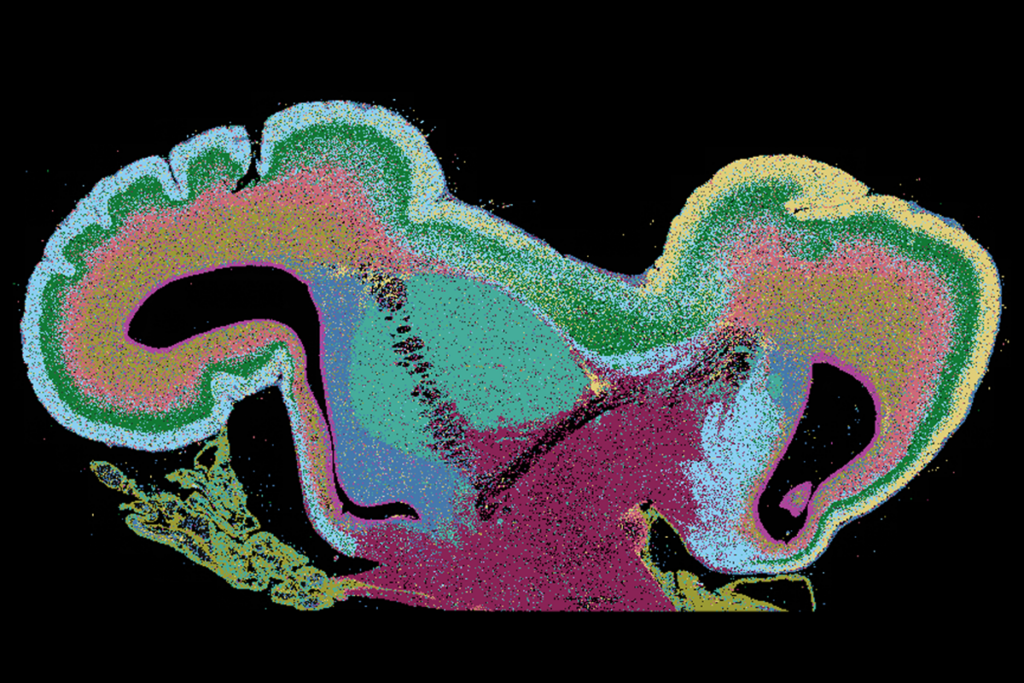

The mGluR-dependent form of LTD, required for immediate translation of mRNAs at the synapse, appears to go awry in fragile X syndrome, a genetic condition that stems from loss of the protein FMRP and is characterized by intellectual disability and often autism. Possibly as a result, mice that model fragile X exhibit altered protein synthesis regulation in the hippocampus, an increase in dendritic spines and overactive neurons.

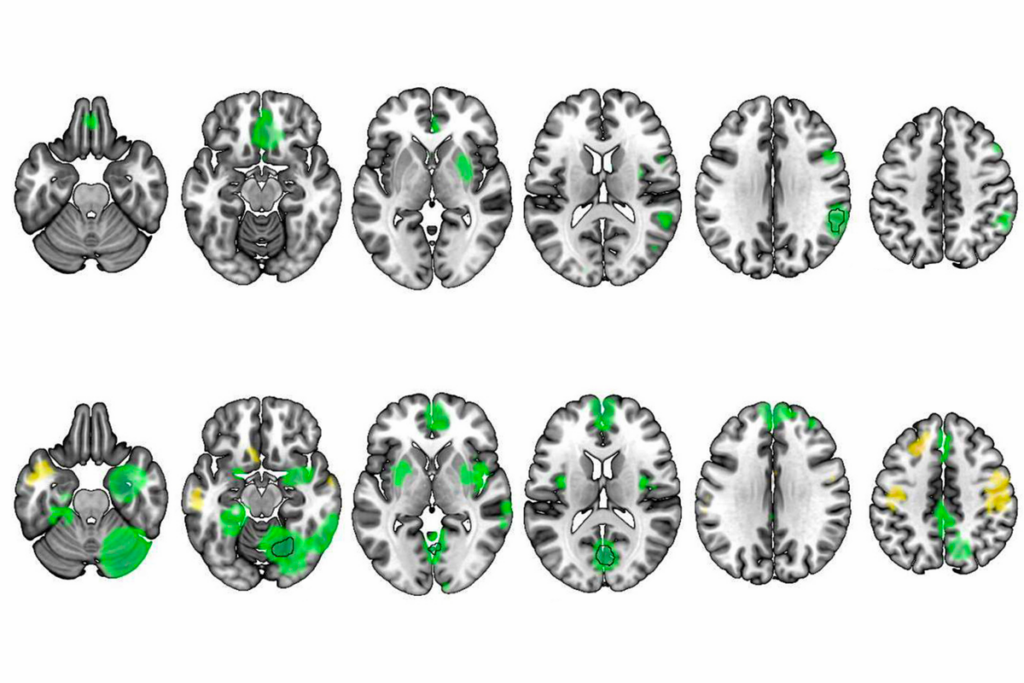

Treatments for fragile X that focus on dialing down the mGluR pathway and tamping down protein synthesis at the synapse have shown success in quelling those traits in mice, but they have repeatedly failed in human clinical trials. But the alternative pathway—via the NMDA receptor—may provide better results, according to a new study. Signaling through the NMDA receptor subunit GluN2B can also decrease spine density and alleviate fragile-X-linked traits in mice, the work shows.

“You don’t have to modulate the protein synthesis directly,” says Lynn Raymond, professor of psychiatry and chair in neuroscience at the University of British Columbia, who was not involved in the work. Instead, activation of part of the GluN2B subunit can indirectly shift the balance of mRNAs that are translated at the synapse. “It’s just another piece of the puzzle, but I think it’s a very important piece,” she says.

Whether this insight will advance fragile X treatments remains to be seen, says Wayne Sossin, professor of neurology and neurosurgery at Montreal Neurological Institute-Hospital, who was not involved in the study. Multiple groups have cured fragile-X-like traits in mice by altering what happens at the synapse, he says. “Altering translation in a number of ways seems to change the balance that is off when you lose FMRP. And it’s not really clear how specific that is for FMRP.”

S

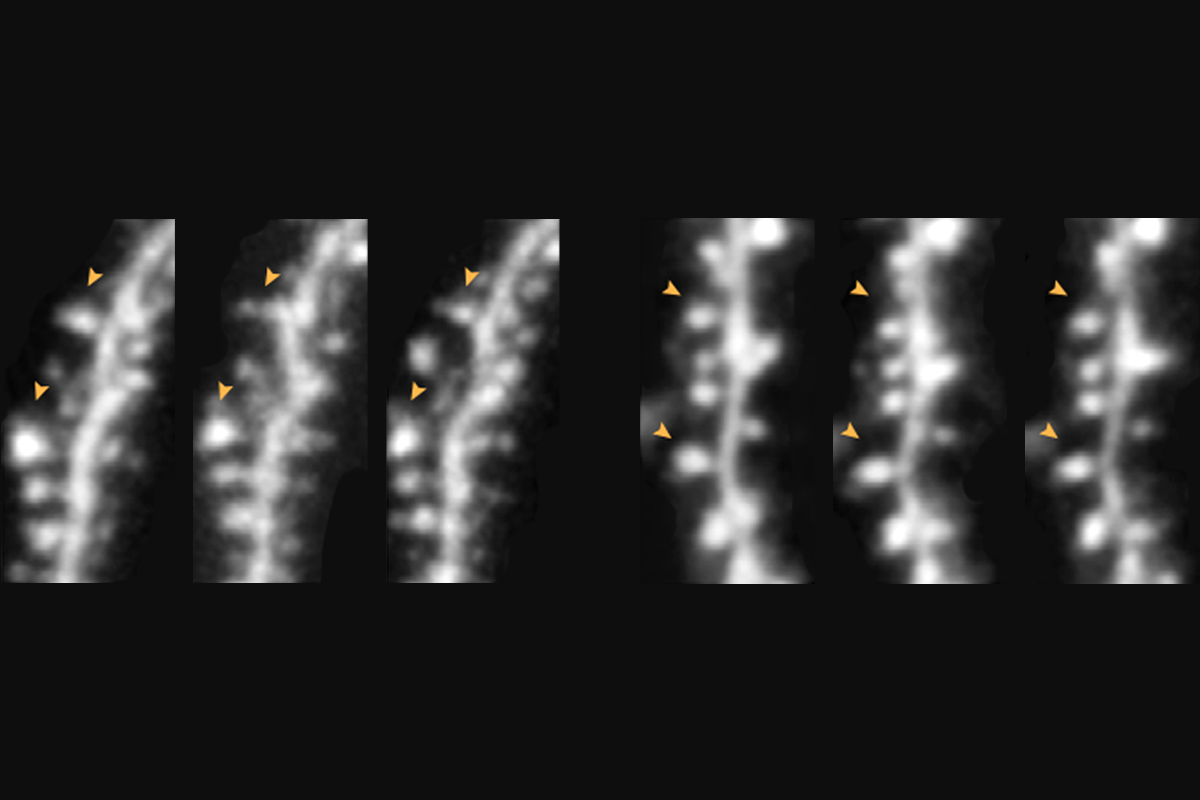

tandard LTD via NMDA receptors results in a decrease in both synaptic transmission and dendritic spine density in the hippocampus in mice. But those effects can be dissociated: Blocking the NMDA receptor ion channel prevents the functional, but not structural, results of LTD through what is known as non-ionotropic signaling, past research has shown.During non-ionotropic NMDA signaling, structural changes to dendritic spines depend on protein synthesis at the synapse for wildtype mice but not for fragile X model mice, that work revealed. In the new study, the same team removed this pathway in the CA1 region of the animals’ hippocampus to understand its contribution to fragile-X-related traits.

Mice engineered to carry the tail end of the GluN2A subunit protein, called the c-terminal domain, in place of the one associated with the GluN2B subunit exhibit fragile-X-like traits, including an increase in protein synthesis at the synapse, the researchers found in the new work. Loss of the GluN2B subunit c-terminal domain also leads to exaggerated LTD as a result of a shift in the kind of mRNAs that are being translated, they report.

For local protein synthesis and this form of LTD, “the volume control is through this part of the NMDA receptor,” says the study’s principal investigator, Mark Bear, professor of neuroscience at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Fragile X model mice crossed with mice carrying excess GluN2B c-terminal domains produced pups without those fragile X traits, Bear and his colleagues found. And model animals treated with the drug Glyx-13, which is thought to target the GluN2B subunits of NMDA receptors, also showed typical levels of protein synthesis and a decreased susceptibility to sound-induced seizures. The work was published in Cell Reports on 20 February.

T

hose findings advance the field’s understanding of how non-ionotropic signaling results in a decrease in the density of dendritic spines, Sossin says, but it is unclear how that relates to behavior. “You know that these spines shrink through this pathway. What does that mean for learning and memory?”And fundamental differences—such as when aberrant protein synthesis correction has an effect or how the human and rodent brain responds to change—may mean that effective fragile X treatments do not translate to people, Sossin adds.

Differences between mice and people, however, are not what derailed the past clinical trial of mGluR antagonists, Bear says. Participants’ neurons showed a “rapid adaptation to loss of the signaling pathway,” leaving minimal time for the treatment to have its effect, but mice showed a similar response in a later analysis, he adds. “We’re quite confident that there was probably nothing wrong with mGluR as a target.”

Bear says that he and his colleagues plan to examine whether mice exhibit the same rapid adaptation to a treatment such as Glyx-13 as they do to mGluR antagonists. And although the new findings do not immediately point to a new way to treat fragile X syndrome in people, he says he hopes it inspires others to pursue this avenue of research. “What I would really hope is that this is a catalyst for people to take notice of this in the context of disease.”