Editor’s Note

We updated this story on 7 September 2023 to add comments from independent experts.

The new tool could help clinicians diagnose autism in children younger than 3, the findings show.

We updated this story on 7 September 2023 to add comments from independent experts.

An electronic tool could help clinicians diagnose autism in children younger than age 3, according to two new studies conducted across six major autism centers in the United States. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has cleared for use a tablet-based version of this instrument.

The scientists detail their findings in two studies published today, one in JAMA and the other in JAMA Network Open.

The tool, which uses eye tracking as a biomarker for the condition, could help address delays in the diagnostic process, its creators say. “Children with concerns about autism typically face a two-year-long clinical odyssey before receiving a diagnosis,” says co-investigator Ami Klin, director of the Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta’s Marcus Autism Center and division chief of autism and developmental disabilities at the Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, Georgia.

Roughly 1 in 36 children in the U.S. has autism, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates. Although 80 percent of parents of children with autism recognize potential developmental issues by the time their child is 2 years old, many children are not diagnosed until age 4 or later. That delay also prevents many of these children from receiving timely intervention.

Currently, only expert clinicians can diagnose autism, but there are not enough clinicians to meet the existing need, says co-investigator Warren Jones, director of research at the Marcus Autism Center and chair in autism at Emory. “If families have access to those experts, then that’s fine, but unfortunately most families do not” — especially families from historically disadvantaged backgrounds.

“This tool is not intended to replace expert clinicians,” Klin says, “but to supplement informed and experienced clinical judgment.” In particular, he and his colleagues hope other people trained to use the device can assist with diagnosis in a clinical setting. This approach could help those children who otherwise face long waitlists, he says.

T

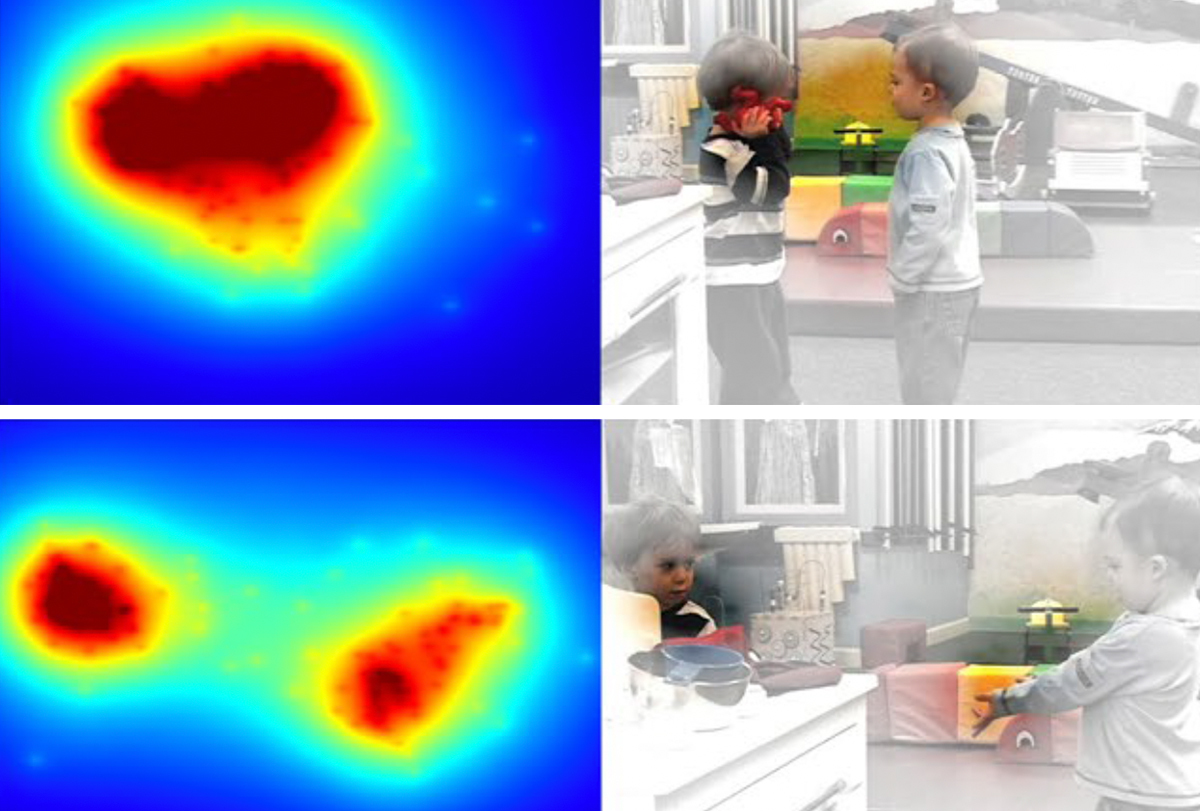

o create a more accessible, automated technique for autism diagnosis, Klin, Jones and their colleagues turned to eye tracking to measure social visual engagement, building on more than 20 years of research in their lab.The new assessment involves asking children to watch movies of same-age peers interacting socially for 8 to 12 minutes. The tool issues a clinical report within 10 to 15 minutes, noting whether a child might have autism, along with estimates of social disability, verbal ability and nonverbal ability, which Jones says may help determine appropriate treatment. Clinicians seeking to use the tool need just one hour of training in advance.

Compared with traditional diagnostic methods, the tool proved 84 percent accurate at spotting children with autism among more than 1,500 toddlers aged 16 to 30 months assessed in three double-blind studies at a half-dozen specialty centers for autism diagnosis and treatment. And the tool showed no bias, whereas the performance of expert clinicians correlated with a child’s race and ethnicity. For example, clinicians gave more autism diagnoses to Hispanic children than to non-Hispanic children — and more autism diagnoses to Black children than to white children.

The FDA cleared the prototype device used in this research in 2022. Klin, Jones and their colleagues have since miniaturized the device for use with a tablet, which the FDA cleared in July. In 2020, Klin and Jones founded a company, EarliTec Diagnostics, which holds the licenses for this work.

They are working on studies to test whether their tool can be used in population-wide screening, detect signs of autism as early as 9 months and help measure the progress and outcome of treatments, Jones adds.

T

he device has still not been evaluated as a screening or predictive test, cautions Lonnie Zwaigenbaum, professor of pediatrics at University of Alberta, who was not involved in this research. Previously established diagnostic tests for this age group, including the Toddler Module for the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS), show better results, he adds.For example, Jones says that in the clinical trial that led to FDA clearance, their device showed 78 percent sensitivity, or correctly identified positive results, and 85.4 percent specificity, or correct negative results. By contrast, the ADOS Toddler Module has sensitivity and specificity ranging from 80 to 90 percent in 12- to 30-month-olds.

Still, in comparison with other diagnostic options, the new tool has certain advantages. These include the fact that it is “easier to administer and does not require specialized clinical training,” Zwaigenbaum says.

The findings with the new instrument also validate the idea that social attention is fundamentally different in the early behavior of autistic children, says Peter Mundy, professor of education, psychiatry, behavioral sciences and neurodevelopmental disorders at the University of California, Davis. To date, he adds, these differences have not been explicitly recognized as a sign of autism.