Study links subset of genetic variants to autism, intellectual disability

Genetic variants across the genome contribute to about 8 percent of the risk for certain developmental conditions — much more than previously thought.

Genetic variants across the genome contribute to about 8 percent of the risk for certain developmental conditions — much more than previously thought, according to a study published last week in Nature1.

The study looked at nearly 7,000 people who have a condition of brain development, such as intellectual disability, developmental delay or autism. The participants are all severely affected, suggesting that their conditions are the result of rare mutations, some of which are spontaneous or noninherited.

The new study found that common variants — those present in more than 5 percent of the population — are also important, however.

Scanning the sequences from the participants, the researchers found that certain combinations of a subset of common variants increase risk of the conditions. These combinations affect the severity of an individual’s condition and yield a ‘polygenic risk score’ for that individual; this may explain why the same rare mutation can have diverse effects in different individuals.

“A really bad mutation in a critical developmental gene is kind of like a bomb going off in the genome,” says lead researcher Jeffrey Barrett, chief scientific officer of Genomics plc, a biotechnology company based in Oxford in the United Kingdom. “The common [variant] signal is how much blast shielding do you have in response to that catastrophic event.”

Many studies focus on causative mutations that are rare and spontaneous. But this approach ignores the rest of the genome, says Santhosh Girirajan, associate professor of biochemistry and molecular biology at Pennsylvania State University.

“[The researchers] are covering the larger aspect of things that most of us are missing. They are saying, ‘Look at the whole genome. Why not look at that, too?’” Girirajan says. “I think that’s fascinating.”

Background effect:

The researchers looked at 6,987 participants in the Deciphering Developmental Disorders database. These individuals have one or more brain condition, such as developmental delay or seizures; 1,121 have autism. The researchers compared the participants with 9,270 controls from the UK Household Longitudinal Study.

The participants all have the hallmarks of conditions that arise from a rare, harmful mutation in an important gene. For example, most of them have additional complications, such as an inherited heart problem or bone defect.

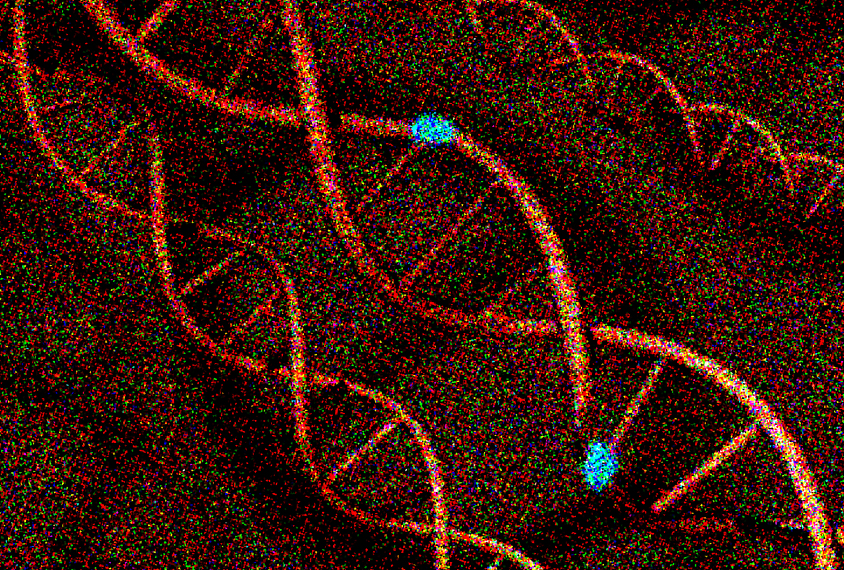

Barrett’s team scoured millions of variants in the genomes of both participants and controls. The sample size is too small to link any particular variant to a condition, but they found a set of variants that increases risk.

The researchers confirmed the importance of this set of variants in an additional 728 participants with one or more of the conditions and their parents.

This set of variants overlaps with one that is linked to schizophrenia; it does not overlap with common variants linked to autism in a previous study. However, the participants with autism are more likely to carry the previously identified variants than those with other conditions, such as intellectual disability.

Specific effects:

The findings suggest that a different set of common variants predisposes an individual to autism than to intellectual disability, says Elise Robinson, assistant professor of epidemiology at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, who was not involved in the study. “It speaks to the role of common variation in distinguishing certain biological features of intellectual disability and autism,” she says.

The new study does not offer explanations for how common variants modulate the risk from rare mutations, Girirajan says. “It would be important to know how such common variants affect biological mechanisms that modulate the neurodevelopmental phenotypes,” he says.

One possibility is that common variants compensate for the effect of a harmful mutation by increasing expression of the unaffected copy of the gene.

Barrett’s team is trying to trace the pathways that their set of common variants affect. He says researchers may eventually be able to use an individual’s set of common variants to gauge her predisposition to specific conditions.

References:

- Niemi M.E.K. et al. Nature Epub ahead of print (2018) PubMed

Recommended reading

Too much or too little brain synchrony may underlie autism subtypes

Developmental delay patterns differ with diagnosis; and more

Split gene therapy delivers promise in mice modeling Dravet syndrome

Explore more from The Transmitter

Proposed NIH budget cut threatens ‘massive destruction of American science’

Smell studies often use unnaturally high odor concentrations, analysis reveals