Study links brain size to regressive autism

Larger brains may be associated with regressive autism, but only in boys, according to a study published online 28 November in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Larger brains may be associated with regressive autism, but only in boys, according to a study published online 28 November in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences1.

Austrian psychiatrist Leo Kanner included large head circumference in his original description of autism in 19432. Since then, studies have found that about 20 percent of children with the disorder have this characteristic3.

However, the significance of these observations has been unclear. The new study is the first to find a link between an increase in overall brain size and other features of autism.

It’s also one of the first publications to come out of the Autism Phenome Project, a longitudinal study aimed at distinguishing among subgroups of autism, based at the MIND Institute at the University of California, Davis. The project comprises comprehensive profiles — including genetic, immunological, behavioral, brain imaging and a variety of other data — of a large number of young children with autism.

“We’re hoping that there’s going to be a series of features that will hang together, that will constitute the definition of a particular type of autism,” says David Amaral, director of research at the MIND Institute and lead investigator on the study.

Antonio Hardan, a child psychiatrist at Stanford University and Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital in Palo Alto, California, who was not involved in the work, says these results are promising. “These are very interesting findings that will help us in the potential identification of subgroups in autism,” he says.

However, Hardan and other scientists caution that the results need to be replicated in studies designed specifically to test a link between regression and head size.

Making connections:

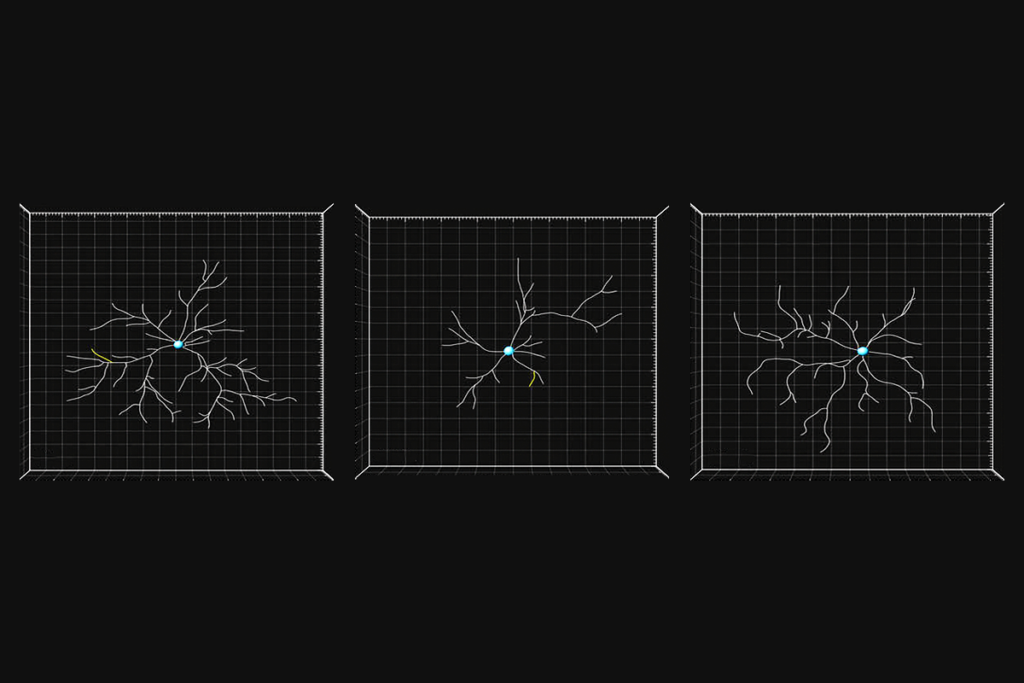

The new study was broadly aimed at exploring associations between head size and a variety of autism characteristics. The researchers used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to measure brain volume in 114 children with autism between 2 and 4 years of age, and 66 typically developing age-matched controls.

“One of the really good things about this paper is the large sample,” says Stephen Dager, professor of radiology at the University of Washington in Seattle.

The researchers divided the children with autism into two groups based on the disorder’s onset. Some children with autism show delays in social and language development from the first months of life. Others appear to develop normally for the first year and a half and then abruptly lose skills starting at 18 to 24 months of age.

Of the participants, 53 children reportedly have early-onset autism, whereas the other 61 have regressive autism.

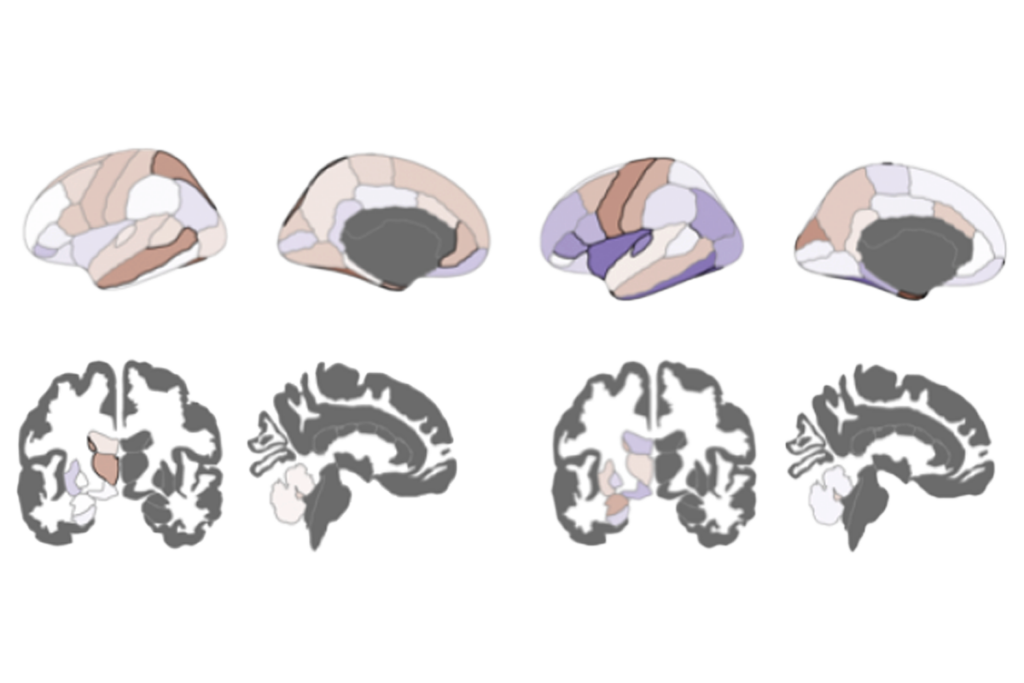

Increased head size is strongly associated with regressive autism, the researchers found. Of the children in the study, scans showed that about 22 percent of boys with regressive autism have extremely large brains — measuring bigger than 97.5 percent of typically developing children. By contrast, only five percent of the boys with early-onset autism have brains that large.

With 22 girls among their study participants, the researchers had a rare opportunity to analyze girls separately from boys. Since autism is four times more common in boys, the vast majority of participants in most studies of head size and autism have been boys, and researchers generally pool the sexes together when analyzing data.

“We were surprised that we didn’t see any differences in brain volume in any of the girls with autism, regardless of whether they had early-onset or regressive autism,” says study co-leader Christine Wu Nordahl, a researcher at the MIND Institute. “I think this is pointing at the idea that girls may be a subgroup of autism.” But she cautions that the number of girls scanned, although it is larger than that in many previous studies, is still too small to consider the question settled.

Looking backward:

To determine whether a child has regressive autism marked by a loss of skills, the researchers asked the child’s parents to answer the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R). Parents also completed a more general survey called the Early Development Questionnaire. If the results of the two questionnaires diverged, a psychologist interviewed the parents to make a firm diagnosis.

Relying on parental assessments of regression introduces some uncertainty into the data, the researchers acknowledge. People don’t always recall past events accurately, and studies over the past two years have shown that parents sometimes miss evidence of regression that trained clinicians pick up4.

Dager, the University of Washington radiologist, says it will be important to confirm the findings in prospective studies that can follow regression as it unfolds, such as those focused on infant siblings of children with autism.

But Paul Law, director of medical informatics at the Kennedy Krieger Institute in Baltimore, says the researchers’ approach was a practical one. “I think a lot of research will continue to be based on parent report,” he says.

He adds that future research could investigate whether head size is linked to the severity of regression. “Anytime there’s a dose response, that really provides strong additional evidence that the phenomenon you’re looking at is real,” he says.

Last year, Law and colleagues reported that children with more severe regression also tend to have more severe autism symptoms, such as lack of speech.

In addition to measuring brain volume with MRI, the researchers charted changes in head size over time using data on head circumference, collected at routine doctor visits before the children had enrolled in the study. Head circumference is a good correlate of brain size in the early years of life.

Based on this information, the researchers found that head size in children with enlarged brains began to diverge from normal when the children were 4 to 6 months of age. If confirmed, says Hardan, “that will be a very nice early indicator of the development of something abnormal that is related to autism.”

References:

1: Nordahl C.W. et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. Epub ahead of print. (2011) PubMed

2: Kanner L. Nervous Child 2, 217-250 (1943) PDF

3: Fombonne E. et al. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 29, 113-119 (1999) PubMed

4: Ozonoff S. et al. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 49, 256-266 (2010) PubMed

Recommended reading

Gene-activity map of developing brain reveals new clues about autism’s sex bias

Parsing phenotypes in people with shared autism-linked variants; and more

Boosting SCN2A expression reduces seizures in mice

Explore more from The Transmitter

Structural brain changes in a mouse model of ATR-X syndrome; and more

Probing the link between preterm birth and autism; and more