Study hints at microbiome differences in children with autism

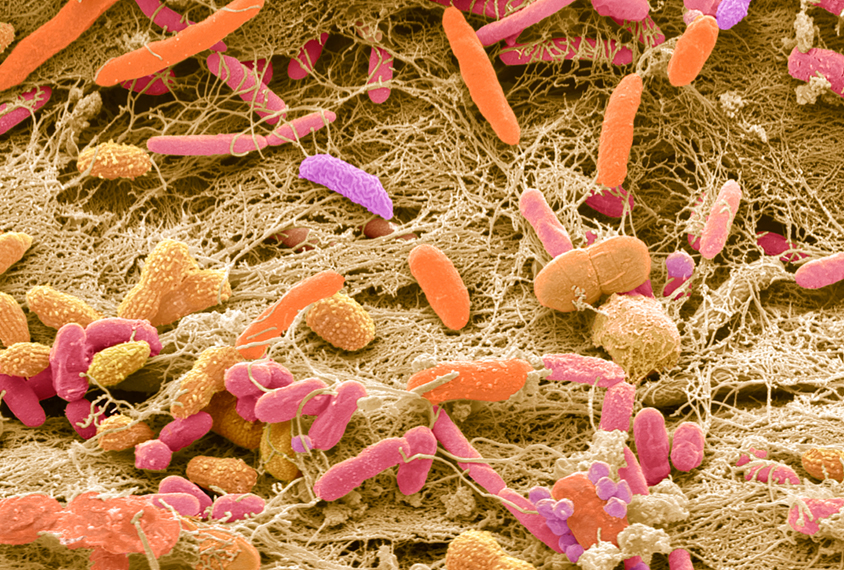

Children with autism may have a subtly different set of bacteria in their gut than their non-autistic siblings do.

Children with autism may have a subtly different set of bacteria in their gut than their non-autistic siblings, according to unpublished data presented virtually on Tuesday at the 2021 Society for Neuroscience Global Connectome.

The prospect that manipulating the microbiome could ease gastrointestinal problems and other autism traits has tantalized many families of autistic children. But studies of the gut microbiome in people with autism are scarce and have shown conflicting results, and mouse studies can be difficult to interpret.

For the new work, researchers recruited 111 families that each have two children — one with autism and one without — born within two years of each other and aged 2 to 7 years old.

“We tried to be as careful as possible by using a control cohort that were siblings,” says study leader Maude David, assistant professor of microbiology at Oregon State University in Corvallis. This study design helped control for variables such as household environment, pets and other factors that can shape the microbiome, she says.

The researchers collected stool samples from the children at three time points, two weeks apart. The repeated sampling reduced the likelihood that short-term shifts in the children’s gut microbiome — due to transient environmental influences, such as day-to-day dietary changes — would skew the results.

Families also shared information about their children’s autism behaviors; dietary habits; use of vitamins, supplements and antibiotics; and gastrointestinal and general health. The information yielded a rich ecosystem of metadata that the researchers could use to sort out potentially confounding variables when looking for differences in groups of organisms, or taxa.

“When we look at all of these, we still find some taxa that are a little bit different in the kids with autism,” David says.

Stool on:

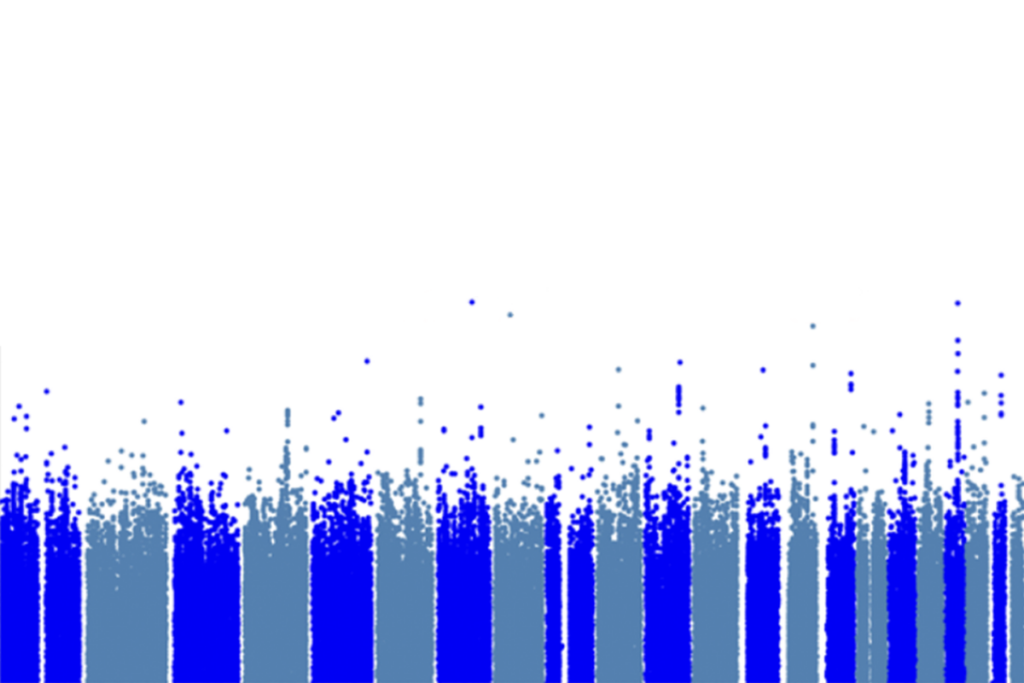

David and her team analyzed microbial genetic material in 432 stool samples from 72 families. They found eight bacterial genetic sequences that were more likely to be present in the guts of children with autism than in their non-autistic siblings, and three sequences that were less likely.

Exactly which species of bacteria these represent or what their functional consequences are is not yet clear, David says. The researchers are conducting more detailed sequencing of microbial genetic material from some of the samples.

The team also conducted a statistical analysis to probe links between the children’s microbiome and various lifestyle and dietary factors. They found some variables that influence the microbiome and that are also associated with autism.

For example, autistic children are more likely to be lactose-intolerant and eschew dairy, and they also tend to eat less fruit than non-autistic children do. Both dietary habits can have a powerful impact on the microbiome.

Such data provide context in interpreting differences between the two groups, David says.

As another check of their results, the researchers used a machine-learning algorithm to predict whether children were autistic or not based on various combinations of the metadata they had collected. The algorithm’s accuracy improved modestly when they also added information about the gut microbiome, which the researchers say is further evidence of small but real microbiome differences in children with autism.

The researchers plan to analyze gene expression, inflammatory markers and metabolites in the samples. They are also testing six compounds that are more prevalent in the stool of the non-autistic participants to see if they have an effect on behaviors reminiscent of autism in mice lacking the autism-linked gene CNTNAP2.

Read more reports from the 2021 Society for Neuroscience Global Connectome.

Explore more from The Transmitter

Remembering Annette Dolphin, who helped explain gabapentin’s effects