The population of older people with autism is set to increase dramatically in the coming decades, but there is little research on how autism affects middle-aged and older adults. Two preliminary studies presented virtually Monday and Tuesday at the 2021 Society for Neuroscience Global Connectome suggest that people with autism or autism traits may be especially vulnerable to brain aging and cognitive decline.

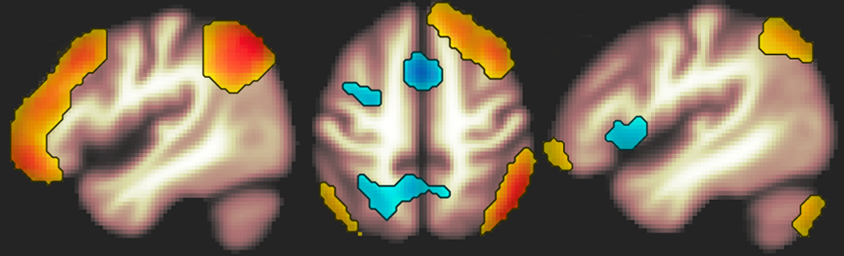

In one study involving 13 men with autism and 18 typical men aged 40 to 64, researchers scanned the participants’ brains twice, roughly two years apart. They analyzed functional connectivity, a measure of synchronized activity across brain regions, as the participants rested quietly in the scanner.

In the autistic men, from one scan to the next, a region known as the left inferior frontal gyrus became less integrated with the rest of the frontoparietal network, the team found. This spot in the prefrontal cortex has been implicated in monitoring errors — especially picking up on errors via social feedback, says Melissa Walsh, a graduate student in the laboratory of B. Blair Braden at Arizona State University in Tempe, who presented the work.

The frontoparietal network is involved in planning, impulse control and organizing complicated tasks, a group of skills often known as executive function or cognitive control.

“This is already kind of a network or domain that is fragile” in people with autism, Walsh says.

Among the autistic men, those with greater declines in this kind of connectivity also performed worse —at both time points, but especially later — on a test in which they had to arrange cards by shape, color or number, intuiting the rules and switching strategies when the rules changed. This test is known to detect early cognitive decline.

The researchers plan to continue the study and collect at least two to four brain scans on at least 25 men and 20 women with autism, as well as controls. They are also analyzing how brain aging may differ between men and women on the spectrum.

Although the current sample is relatively small, the results hint that autistic adults may be prone to more pronounced brain aging than their typical peers, Walsh says. Pharmacological interventions or transcranial magnetic stimulation to improve function in the frontoparietal network in older autistic people might be helpful, she says.

Aging spectrum:

In a second study, researchers showed that vulnerability to brain aging may extend to the ‘broad autism phenotype,’ an estimated 5 to 10 percent of the population who have autism traits but do not meet the threshold for a diagnosis.

Previous studies have shown that older adults with autism traits often have difficulty with executive function and social cognition, says Alex Job Said, an undergraduate at the George Washington University in Washington, D.C. and manager of Gregory Wallace’s lab. “We wanted to understand it more in terms of neuroanatomy.”

The team imaged the brains of 166 people aged 49 to 81. The participants, three-quarters of whom were female, also underwent a battery of neuropsychological tests and completed the Autism Spectrum Quotient, a questionnaire that measures autism traits.

The quartile of participants who scored highest on the questionnaire — that is, the group with the most autism traits — had a smaller hippocampus, right amygdala, left thalamus and a portion of the cerebellum compared with the rest of the participants, the researchers found. And the higher a person’s score, the smaller their hippocampus, left thalamus and left cerebellar cortex were likely to be.

The hippocampus, thalamus and cerebellum decrease in volume during middle and older adulthood in the general population. The study provides further confirmation of the broad autism phenotype, and hints that people in this group may have accelerated or more pronounced brain aging, Said says. In future studies, the researchers plan to look in more detail at the cerebellum in this group of older adults.

Read more reports from the 2021 Society for Neuroscience Global Connectome.