Stubborn as a Stone

What scientists find to be true, and how the media represents it, are often at complete odds.

What scientists find to be true, and how the media represents it, are often at complete odds.

Last week, ABC aired the debut episode of a new TV show, Eli Stone, in which the title character wins a $5.2 million lawsuit after arguing that vaccines can cause autism.

At the same time, two independent studies, both published in reputable journals, dismissed a link between autism and either the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine or the mercury-based vaccine preservative thimerosal.

Following calls from the American Academy of Pediatrics to cancel the show, ABC ran a disclaimer reminding viewers that the story is fictional, and referred them at the end of the episode to a CDC website for information about autism.

The AAP reacted by pushing up the release of a study in the February issue of Pediatrics that shows that thimerosal is metabolized much too fast by the body for it to have a chance to build up or cause any neurological damage.

Thimerosal contains ethyl mercury, which is distinct from the neurotoxin methyl mercury, found in fish and other sources. Researchers had believed that the two are metabolized similarly.

But when University of Rochester researchers studied 216 healthy infants in Buenos Aires, Argentina, where vaccines still contain thimerosal, they found that the half-life of ethyl mercury in the blood after vaccination is 3.7 days, compared with 44 days for methyl mercury.

Most of the mercury seems to be eliminated through stools, where mercury levels linger slightly longer than in blood, but there is no evidence of mercury in the urine.

In a second study published today, British researchers found that children given the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine, or MMR, arenʼt at greater risk of autism.

The study, the largest of its kind, looked at 98 children with an autism spectrum disorder; 52 children with special educational needs, but no evidence of autism; and 90 normally developing children, all between the ages of 10 and 12.

The 1998 Lancet paper that began the MMR-autism debate had suggested that the measles virus in the vaccine triggers an abnormal immune response in some children that can then cause autism. The paper was later retracted, but the damage was done: MMR vaccination rates in Britain fell from 92 percent in 1996 to 80 percent in 2004, well below the 95 percent needed to keep these diseases from circulating in the population.

In the new study, published in the journal Archives of Disease in Childhood, researchers took blood samples from the children and found no difference in the levels of measles virus or antibodies between those with autism and those without.

Hereʼs something to ponder: how many of the nearly 13 million people who watched that episode of Eli Stone also read reports of these two studies??

Recommended reading

Expediting clinical trials for profound autism: Q&A with Matthew State

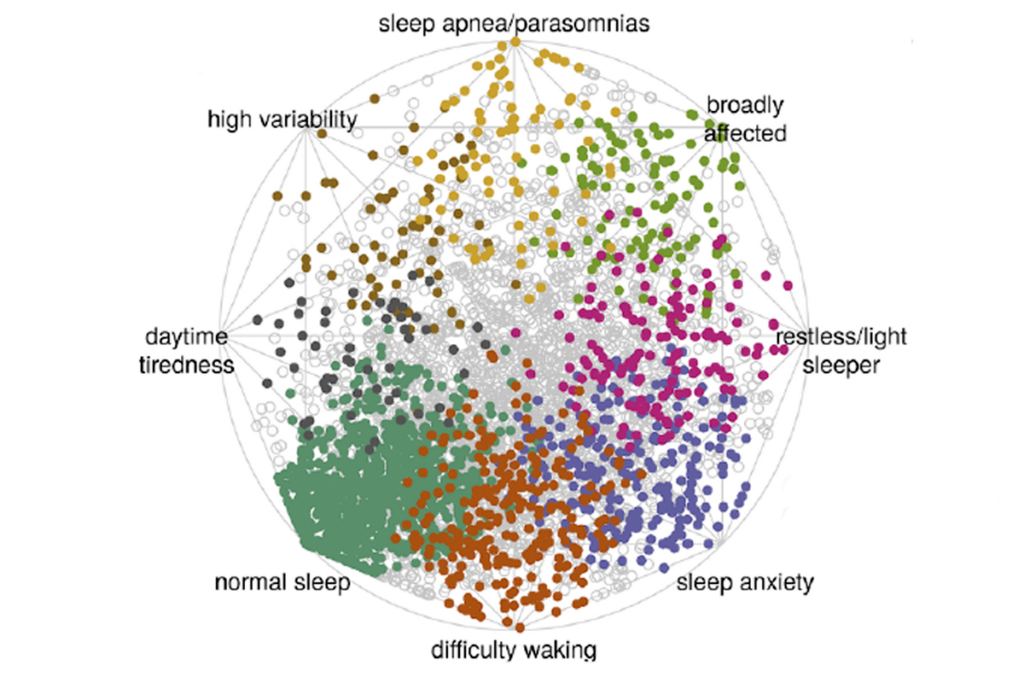

Too much or too little brain synchrony may underlie autism subtypes

Explore more from The Transmitter

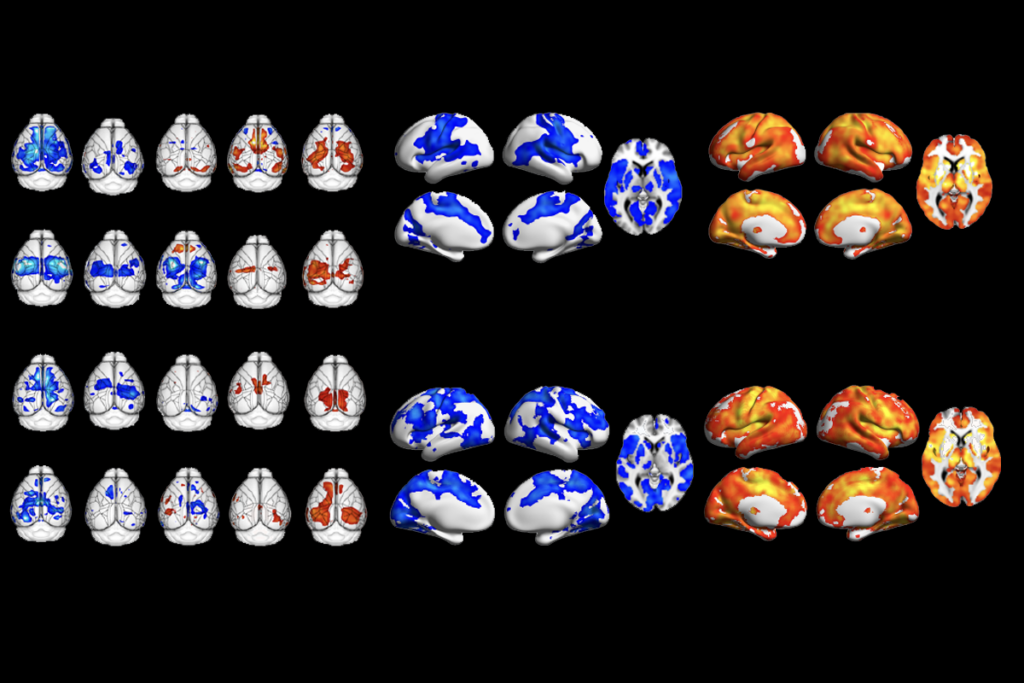

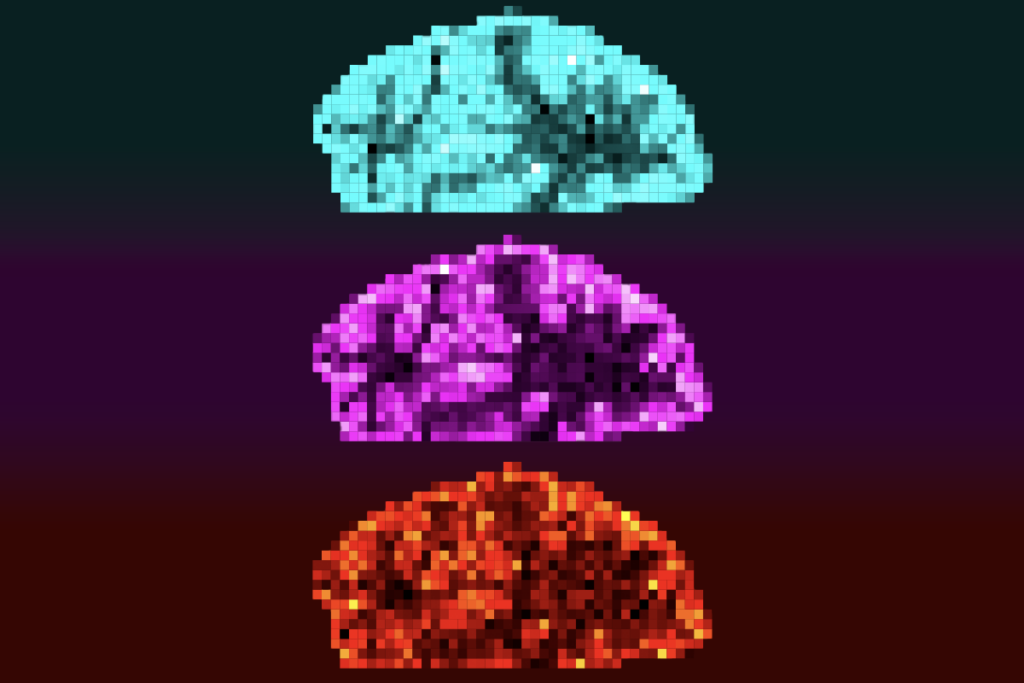

Mitochondrial ‘landscape’ shifts across human brain