Autistic children younger than 2 years have brain structure differences that predict atypical language development, according to two new imaging studies.

Researchers presented the findings 14 May at the 2022 International Society for Autism Research annual meeting. (Links to abstracts may work only for registered conference attendees.)

Both studies tracked the brain and language development of ‘baby sibs’ — younger siblings of autistic children, who have an increased likelihood of being diagnosed with autism themselves.

Baby sibs with autism often show signs of language delay at around their first birthday, past research has shown. And many autistic baby sibs also have markers of atypical brain development, such as immature white matter, the bundles of fibers that relay neuronal signals.

“But we had not yet linked those two together,” says Jessica Girault, assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who presented one set of findings.

The results draw on data from the Infant Brain Imaging Study (IBIS), a longitudinal study that has been collecting brain scans of hundreds of baby sibs when they are 6, 18 and 24 months of age. At the same time points, researchers test how well the children understand language and communicate. They also assess the children for autism at 24 months.

G

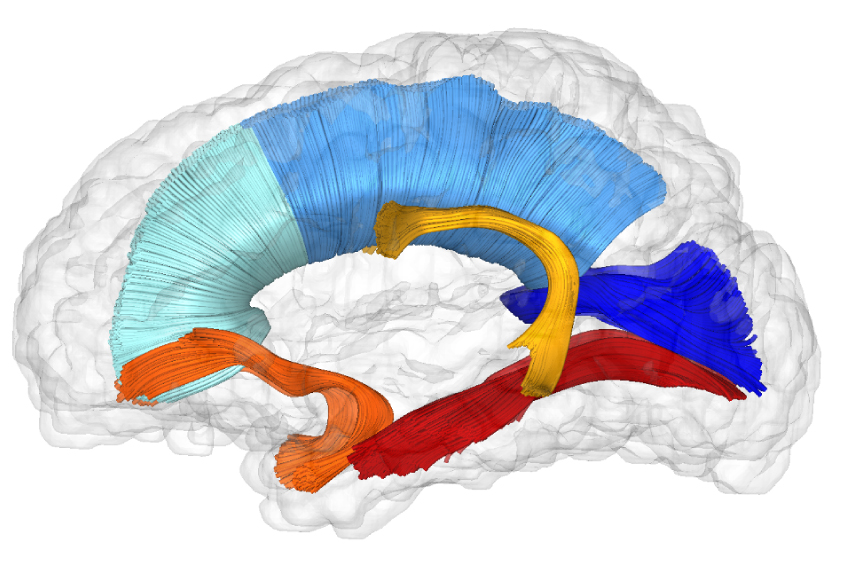

irault and her colleagues tracked the maturation of white matter in 321 baby sibs, 70 of whom have autism, and 140 babies without a family history of autism. As a child’s brain develops, their white matter gains myelin, the fatty insulation around axons that aids signal conductance between neurons. A technique called diffusion tensor imaging captures that change with the metric of fractional anisotropy (FA): More myelination results in a higher FA measure.For the non-autistic children at each age studied, language skills correlate with FA levels in the right arcuate fasciculus — a white-matter tract that links regions of the brain responsible for producing and processing language, the team found. But that correlation was significantly stronger for autistic baby sibs — a difference that became evident by the age of 12 months.

“This suggests to us that mechanisms that underlie the development of white matter during this period — so, fiber myelination and organization — might play a really important role in contributing to heterogeneity in language profiles in autism,” Girault says.

The team plans to continue to investigate this relationship, she says. “It’s the first study of its kind. And we want to make sure that what we’re finding is generalizable.”

I

n the other new study, researchers tracked how surface area and cortical thickness of 78 brain regions change over the first two years of life.They examined MRI scans from 239 children — 128 non-autistic baby sibs, 31 autistic baby sibs and 80 non-autistic children with no family history of autism.

They found a number of brain regions whose sizes were strongly associated with language skills, but the relationships between brain region volumes and cortical thickness were different for each of the three groups of children.

Despite these inconsistent relationships, the results are a starting point for further research, says Luke Moraglia, a graduate student working with Meghan Swanson at the University of Texas at Dallas who presented the findings. The autistic group did have the most regions associated with language, as well as the largest effect sizes.

They also found associations across every brain lobe and in many regions not typically associated with language, such as the fusiform gyrus, which is usually involved in visual processing. This range highlights the fact that the infant brain is not yet specialized, Swanson says, and suggest that the path to specialization is different in autistic children.

“You can’t just look at this classic language model on the left hemisphere and think that you’re getting the whole picture,” she says. “It’s like if you dropped your keys, and you’re looking only underneath the lamppost — they could be outside of where the lamppost is showing the light.”

Read more reports from the 2022 International Society for Autism Research annual meeting.