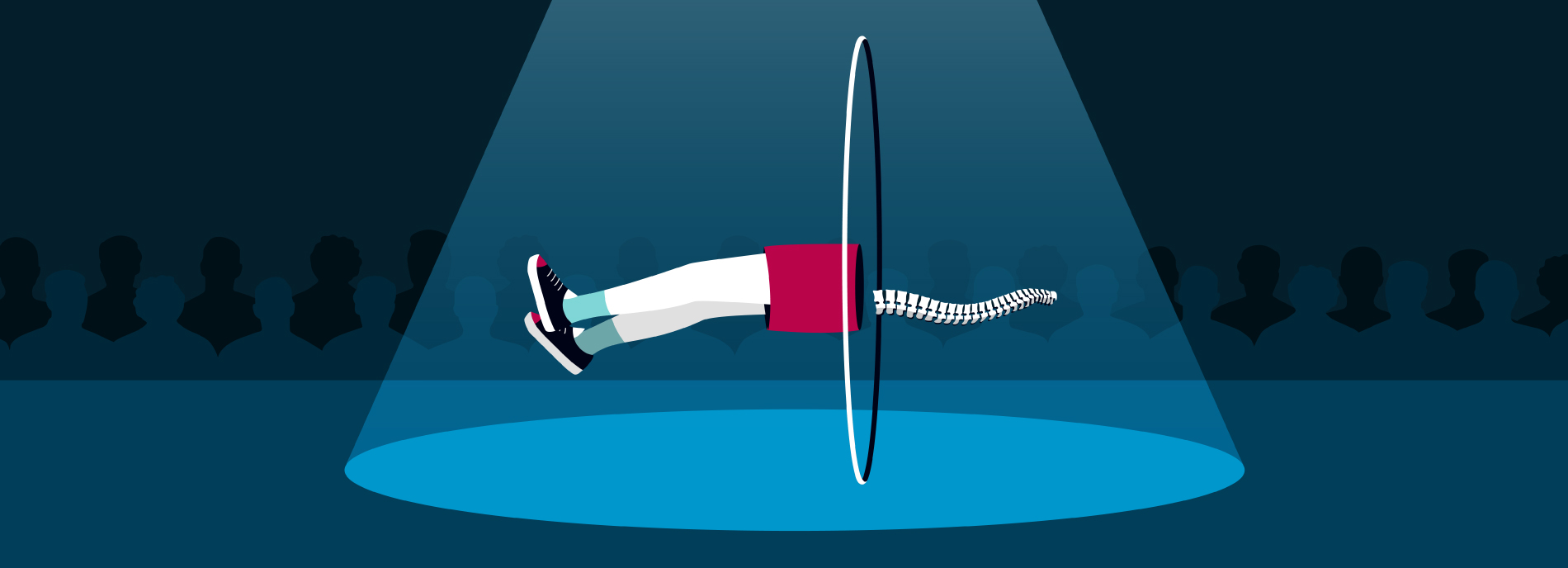

Straightening out chiropractic’s claim as a treatment for autism

Some chiropractors advertise that they can treat autism, but there’s no evidence to back that claim.

B

radley was just 2 when his persistent communication problems landed him with an autism diagnosis.His mother, Jayme Frear, made adjustments to Bradley’s diet and lifestyle. His uncle, a chiropractor, suggested the toddler try chiropractic treatments. That made a remarkable difference to the boy’s well-being, says Frear. Bradley is now 10 and doing well in a mainstream elementary school class, she says. “Our son went from a child that didn’t communicate to what he is today.”

Bradley wasn’t the only one apparently transformed by the visits. His mother, who was a nurse at the time, became so convinced of their value that she altered her career path. She trained as a chiropractor herself and now occasionally sees autistic children who have musculoskeletal complaints in her Florida practice. But many chiropractors advertise that they can treat autism traits by manipulating the spine; some have even invented their own unproven techniques, which they claim can “correct autism.”

Many parents are drawn to these treatments, which can cost more than $50 a session. By one 2015 estimate, approximately 88 percent of children on the spectrum in the United States have used complementary and alternative medicines. Among practitioner-based alternative medicine options for children in the U.S., chiropractic treatment is the most common, according to a 2008 National Health Statistics Report.

There is little research on chiropractic’s benefit for autistic people. A systematic review of the literature in 2016 found only one collection of cases, 11 individual case reports and one clinical trial with 14 participants but no controls. The researchers who compiled the review deemed the single trial of poor quality and the reporting in the collection of cases “insufficient.” Though the case reports all described some benefit, the researchers say that evidence is too scarce and too weak to be reliable. A 2010 analysis reached the same conclusion: “Inconclusive safety, inconclusive efficacy: Discourage,” wrote its authors.

Nor is evidence likely to be forthcoming any time soon. Experts note there is no plausible explanation for how chiropractic treatments could have any effect on autism. “If I heard a parent telling me that that was what they were pursuing for a child, I wouldn’t hesitate to tell them that that is nonsense,” says Suzanne Lewis, chair of the advisory committee for the advocacy group Autism Canada. “You can’t change brain function by moving suture plates or cranial plates or dropping the soft palate or whatever else they might be promoting,” she says. “There’s no evidence that it makes any benefit — and at best you’re lucky that it doesn’t cause harm.”

True believers:

H

ow exactly did chiropractors get the idea that moving vertebrae could alter the course of a condition such as autism?The explanation harks back to the earliest days of the profession. Chiropractic was invented in the late 1800s by Daniel David Palmer, a former grocer and deeply religious ‘magnetic healer.’ Palmer subscribed to ‘vitalism,’ a philosophy espousing the idea that a vital force animates all living things. He asserted that this force, which he called ‘Innate,’ flows from God to the body via nerves passing through the spine. He said this force keeps the body in good health. And he taught that blockages in the spine, or ‘subluxations,’ can degrade or stop its flow and lead to disease. In Palmer’s view, chiropractors could remove subluxations by adjusting the vertebrae of the spine, allowing the body to heal itself of anything from deafness to heart disease.

Mainstream medicine has advanced dramatically since Palmer’s time, but his prescientific, vitalist ideas continue to thrive within the chiropractic community. As much as 30 percent of contemporary chiropractors in North America proudly practice in the vitalist tradition. As such, they view autism as one of dozens of conditions they can treat by ‘removing blockages.’

These chiropractors are not just at the fringes of the field. Clifford Hardick — past president and current member of the regulatory board that oversees more than 5,000 chiropractors in Ontario, Canada — is a dyed-in-the-wool vitalist. In a 2017 speech to chiropractors at a conference in Atlanta, he boasted of his success in treating children with developmental delays: “We get those kids coming in. They’ve been in speech therapy for nine months and they can say three words, and after just four or five adjustments over about two or three weeks, their therapist is saying, ‘I can’t figure out what’s going on; they’re starting to build sentences.’ That’s what chiropractic is! That’s what chiropractic is!”

His audience clapped enthusiastically, but not everyone is a fan. Public health advocate Ryan Armstrong submitted a formal complaint against Hardick in 2017 to the College of Chiropractors of Ontario, alleging that Hardick used “misleading and inappropriate advertising,” among other complaints. (He does not specifically name autism in the complaint.) But in a ruling released in May, the college concluded that it had no grounds to discipline Hardick. (Hardick did not respond to repeated requests for comment.) Regardless, most experts say such anecdotes are not supported by research: “We don’t have any current evidence to make any sound, safe statements,” says Katherine Pohlman, clinical research scientist at Parker University in Dallas, Texas, who studies the safety and efficacy of chiropractic treatments.

Some chiropractic researchers admit there is scant evidence but still recommend short trials of adjustments for autistic children, provided the practitioner is transparent about the lack of evidence and makes no claims of a cure. (Many autistic children have gait and other motor problems.) But that sets the evidence bar too low, says Timothy Caulfield, professor of law and public health at the University of Alberta in Edmonton. “It may be tempting to say, ‘Well, I’ve heard it helps for some,’ because that is easier than saying, ‘There is no good clinical evidence to support this practice,’” Caulfield says. “But the law — and clinical ethics — demands that [chiropractors] be honest with their patients.”

That’s especially important for parents who are all too willing to believe. The more anxious parents are, the higher the chances they’ll turn to things like pseudoscience, says Anne Borden, who has a 9-year-old autistic son and founded the Campaign Against Phony Autism Cures. “Then there’s a whole culture of autism parents where they have the support groups and they have coffee chats. None of these are mediated; the parents get together and they share all the pseudoscience nonsense with each other.”

In particular, such parents focus on positive outcomes over any potential negative aspects of the treatment. The 2016 review of the existing literature on chiropractic treatment for autism did not find any reports of adverse events, but that does not mean there weren’t any, researchers say.

Even if the risks were zero, there are still no plausible explanations for how spinal manipulation might treat autism in children. Yet an entire industry has sprung up to fill that gap. For example, Wellness Media produces a brochure titled “Autism and Chiropractic.” The language in this brochure is persuasive and might sound legitimate to anyone unfamiliar with science: “By correcting subluxations your chiropractor will help restore balance to the nervous system and … help reduce behaviour related symptoms while simultaneously increasing digestive and immune function through increased activity of the parasympathetic nervous system.”

Chiropractic promotional websites such as Upper Cervical Marketing and Upper Cervical Awareness also supply ready-made pseudoscience for chiropractors trying to sell their services: “The atlas (C1) and axis (C2) vertebrae are located in a part of the body that affects everything from proper brainstem function to the free flow of blood to the brain,” says one posting on Upper Cervical Awareness. “If you or a loved one is suffering from [autism], it makes sense to get an examination from an upper cervical chiropractor.” Similar marketing and consulting firms produce websites featuring articles and case reports that chiropractors use to bolster their claims.

Buying pseudoscience:

R

oger Turner, a 70-something chiropractor based in Barrie, Ontario, makes even bolder assertions. Turner advertises that he can “correct” autism using his ‘Turner Method.’ He says he has treated at least 4,000 children and trained 1,400 chiropractors in his method over the past 15 years.Turner focuses his eponymous technique on the skull because he says the birth process or early childhood injuries can compromise the space between the skull and the brain, decreasing the available blood supply and cerebrospinal fluid. He says the root cause of autism and other neurodevelopmental conditions could be a misalignment of cranial plates.

Turner points to a shopping list of other unproven contributors to the condition, including yeast infections, heavy metal toxicity, microwaved foods and a generalized ‘toxic’ environment. But “the most important factor, the one that is missed by most treatment protocols, is the ability of the brain to function without interference,” he says.

Turner described his first treatments of autistic children in July 2008 in Canadian Chiropractor, a trade magazine for practicing chiropractors. One child’s inconsolable crying stopped after her first cranial adjustment, much to the relief of the rest of the family, he wrote in the article. After three weeks of adjustments, the 7-year-old had gained control of his bowel functions and had stopped wearing diapers. “This is where we saw our first complete reversal with the use of cranial adjusting,” Turner wrote. He noted that parents of 16 other autistic children also signed up after hearing about this progress.

Two years later, Sandy Hart-Lehmann took her 9-year-old son Christopher to see Turner. Today, she says she felt duped after spending at least 5,000 Canadian dollars (about $3,700) on Turner’s treatments for a year and a half without any results. She says at the time she was trying everything possible to help her son, acting out of “sheer, terrifying desperation.”

The visits to Turner ended when Christopher himself refused the therapy. “‘No Dr. T,’ he said,” Hart-Lehmann recalls. It was the first time her son, who is gentle and compliant, had ever declined treatment. Today, Christopher, at 19, enjoys fine dining and vacation cruises and is an avid collector of monster truck models. He is finishing high school, continuing with speech and diet therapy and transitioning into adult services.

Responding to Hart-Lehmann’s comment, Turner said, “We’re there to help the kids. Unfortunately, we don’t get 100 percent results with everybody. Nobody does.”

Regardless, Turner still has many devotees. One of his former students, Michael Fiske, says he has seen six autistic children in his California practice, and four of them started speaking after the treatment. In a phone interview, he described one nonverbal 10-year-old girl in his care: “There was this astonishing immediate change in her where her whole personality suddenly changed: She became joyful, happy, exuberant, [made] eye contact with me, grabbed my hand, was pointing at different things in the room and communicating with me. … It was one of those amazing experiences I’ve had in my life.”

Fiske also treats 6-year-old Brayden, who was diagnosed with autism at 18 months and started seeing Fiske two years ago. At that time, Brayden could say only 10 words and was receiving speech, occupational and applied behavior analysis, says his mother, Carrie Malinoff. After the first treatment — in which Fiske performed what she calls “head squeezes” — Brayden became calmer; after the second and third visits, his vocabulary increased rapidly, she says.

At first, Brayden had intensive therapy, seeing Fiske four times a week, twice a day, at $60 an hour. Today, he sees him about once a week. Despite the other therapies Brayden received, Malinoff is convinced it was Fiske who made the difference, “moving the bones and removing the pressure off the brain and allowing all the fluids to function properly,” she says, providing an account that echoes the language on Fiske’s website. “Brayden wouldn’t have come so far, so fast.”

Without any rigorous scientific studies, parents like Malinoff cannot distinguish a treatment’s efficacy from simple correlation, the placebo effect or confirmation bias: Practitioners want to believe their treatment helps, and parents urgently want to see their children helped. “It is well known that wishful thinking can make parents see things that others do not see,” says Joe Schwarcz, director of the McGill University Office for Science and Society in Montreal. “The question is whether objective observers also note the improvement.”

So far, the lack of rigorous evidence that chiropractic can help autistic children has not dissuaded many parents. Nor has it stopped chiropractors and chiropractic marketing firms from promoting their services to young people on the spectrum and their families. Jayme Frear says she knows that chiropractic doesn’t treat autism directly. “We don’t cure anything,” she says. Her son Bradley continues to have regular treatments.

Syndication

This article was republished in The Atlantic.

Recommended reading

Expediting clinical trials for profound autism: Q&A with Matthew State

Too much or too little brain synchrony may underlie autism subtypes

Explore more from The Transmitter

Mitochondrial ‘landscape’ shifts across human brain