Sponsors of clinical trials may report data late or never

Many clinical trials, including those related to autism, do not report their results within a year of their completion.

Just 41 percent of clinical trials listed on a research registry in the United States reported their results within a year of their completion, a new analysis has found1. And roughly one in three trials reported no results at all.

The problem is even more pronounced among the subset of trials that focus on autism, a Spectrum analysis has found. Only 20 percent of those trials reported their results on time.

Delayed or absent reporting of clinical-trial results can deprive both scientists and laypeople of critical information about the effectiveness and side effects of treatments.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Amendments Act of 2007 requires researchers to register trials of treatments on clinicaltrials.gov and to post their results within a year of completion, regardless of what they find or whether they also plan to publish them in a peer-reviewed journal.

In January 2017, the government added a ‘final rule’ that said trial sponsors who did not comply with the requirements could be fined $10,000 a day. (That figure, which is pegged to inflation, has since risen.)

Despite these steps, the majority of trial sponsors have not disclosed their data.

“The main takeaway is that people are not complying,” says Nicholas DeVito, a doctoral student in Ben Goldacre’s lab at the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom who worked on the analysis. “It’s a major problem.” (Goldacre did not respond to multiple interview requests.)

Missing data:

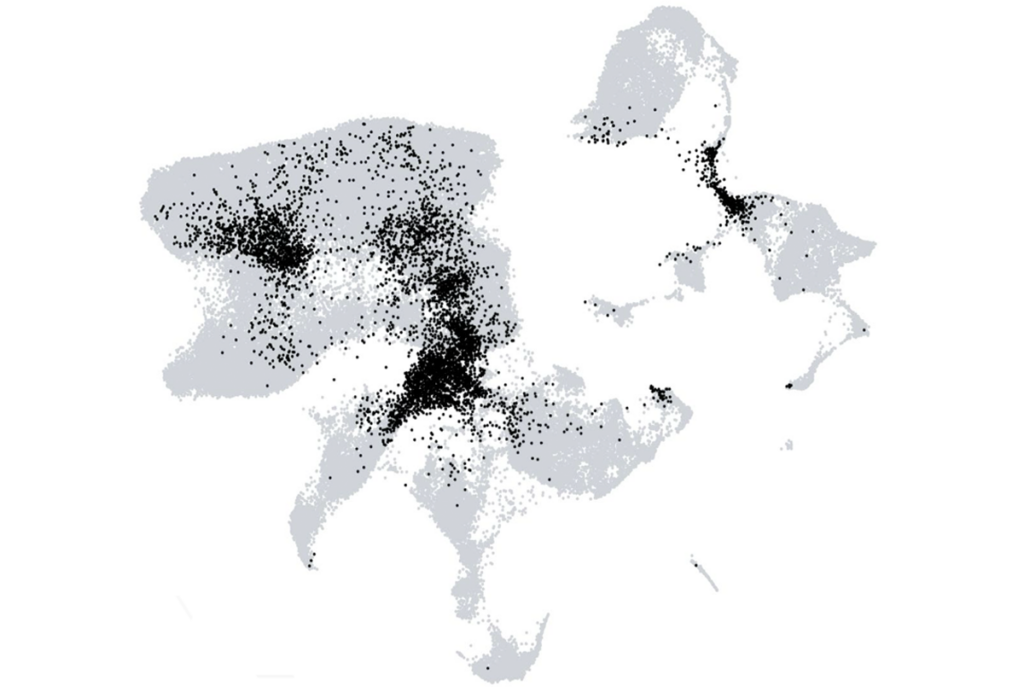

DeVito and his colleagues identified 4,209 registered trials that were due to report their results between mid-January 2018 and mid-September 2019. Of these, just 1,722 trials posted their results on time, and 1,523 did not report any results at all.

Industry-sponsored trials are the most likely to meet the requirements, the team found: 50 percent compared with 34 percent of non-industry trials and 31 percent of trials sponsored by the U.S. government.

“I think it’s safe to say that a Pfizer or a GlaxoSmithKline or other major pharmaceutical companies like that have very good internal structures and lawyers and compliance officers who ensure that once these laws are implemented, they are following them,” DeVito says.

The researchers also found no evidence that the FDA had imposed any financial penalties on delinquent trial sponsors. “As far as we can gather, they’re not availing themselves of these mechanisms to increase compliance,” DeVito says.

If the FDA had levied the fines, he says, it could have collected more than $4 billion: “Compliance is only ever going to be as good as enforcement.”

The results were published 17 January in The Lancet.

Autism absences:

In an effort to increase transparency, DeVito and his colleagues built TrialsTracker, a public database that keeps tabs on the data-reporting compliance of registered trials.

Spectrum used the database to identify 15 autism-related trials that were due to report results sometime after January 2018. Of the 15, only 3 reported results on time, 6 did so between 1 and 304 days late, and the remaining 6 had yet to report any results at all, as of 23 January. Three of those are more than a year overdue.

The longest delay belongs to Erchonia Corporation, a Florida-based company that develops medical devices designed to treat a variety of conditions with low-powered lasers. Erchonia was due to report the findings from its trial, a study of whether low-level laser light therapy can ease irritability in children with autism, on 28 October 2018.

Steven Shanks, president of Erchonia, says he was unaware the results were overdue. “I appreciate you bringing it to my attention,” he told Spectrum, adding that the results will be posted “relatively soon.” Erchonia posted its results on 26 January, after speaking with Spectrum.

Shanks said it had taken his team a long time to get the trial up and running, and that they had not completed their analysis until a few weeks earlier. “Research always takes a lot longer than I expect,” he says.

Unexpected delays:

Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston has two delinquent autism trials in the database: a trial of whether oxytocin can improve social engagement in young adults with autism, which was due to report its results in November 2018; and one testing whether memantine, a drug typically used to treat dementia, can improve social functioning in autistic children. Results from the latter appeared 86 days late.

“Due to the complexity of its design and challenges in recruiting, the findings are inconclusive thus far,” Michael Morrison, director of media relations at the hospital, says about the oxytocin trial. “However, data analysis is ongoing, and the investigators intend on reporting their results as soon as they are finalized.”

Morrison disputes the labeling of the memantine trial as late, however, saying that the database does not reflect an extension the researchers received from the funding agency. The extension pushed the study’s date of completion, and thus the deadline for reporting results, by more than six months.

DeVito notes that extensions do not erase researchers’ obligation to update their trial completion date in the federal registry. “If and when they update it, that will be reflected on the TrialsTracker,” he says.

Other researchers with late results told Spectrum that they sometimes forget to go back to the registry to close out a trial or that they had been using the registry for the first time.

“There was a bit of a learning curve for me,” says Jill Hollway, a research scientist at Ohio State University in Columbus, who was 45 days late in posting results from her trial on the effect of essential oils on autistic children’s quality of life.

References:

- DeVito N.J. et al. Lancet Epub ahead of print (2020) PubMed

Recommended reading

Explore more from The Transmitter

ABCD Study omits gender-identity data from latest release

Neuropeptides reprogram social roles in leafcutter ants