Minimally verbal autistic people demonstrate familiarity with spelling patterns, a new study suggests. But several communication researchers who were not involved in the work say they worry the finding could be used to support a controversial communication method.

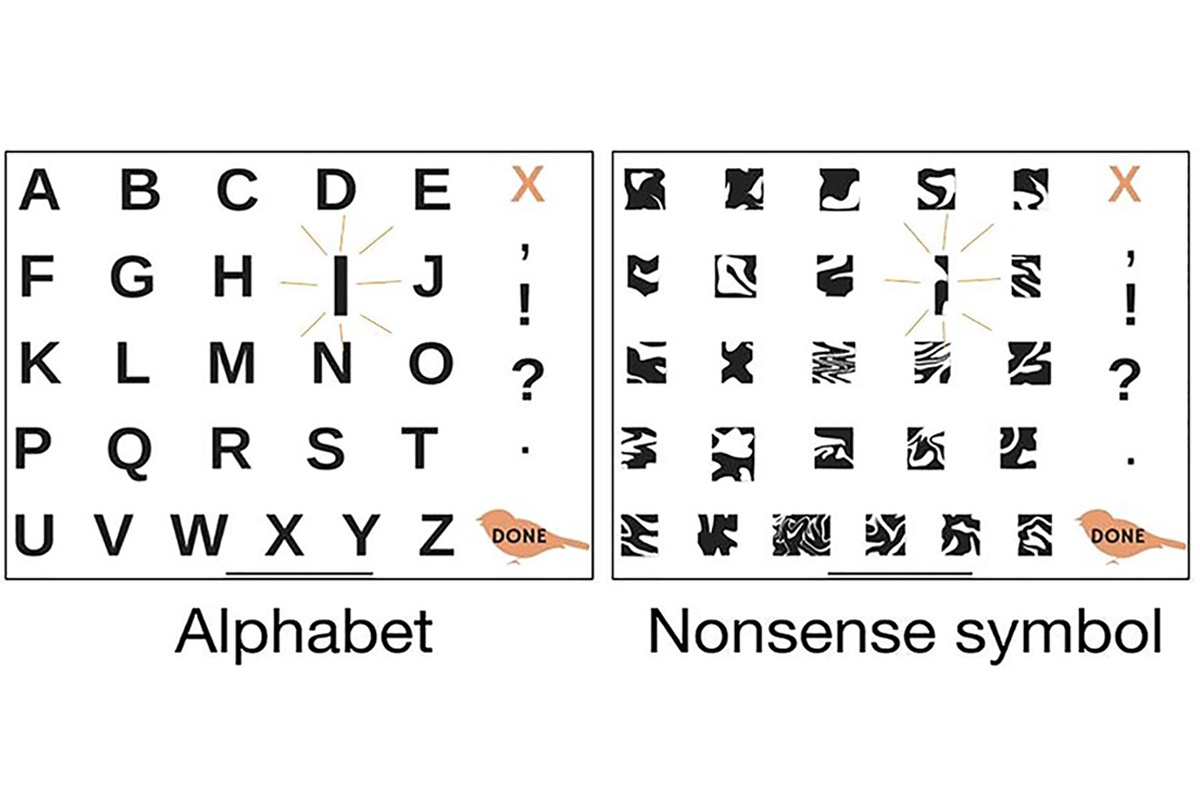

In the study, 31 teenagers and adults with autism played a letter-tapping game reminiscent of Whac-A-Mole on a tablet computer, says lead investigator Vikram Jaswal, professor of psychology at the University of Virginia. The participants tapped letters on an alphabetical grid as they flashed one at a time. In some trials, the flashing letters spelled out a meaningful sentence that the researchers had previously read aloud to the participants.

About half of the participants tapped the letters faster when they were part of a meaningful sentence or common letter pairing (such as “he”). They also tapped letters faster than nonsense symbols and paused before tapping the first letter of a new word in the sentence.

These participants showed “foundational literacy skills,” Jaswal says, though hyperlexia, or an intense fascination with letters, could also explain these results, his team states in the study. The paper was published 21 February in Autism.

The reaction-time task is a standard way to measure implicit knowledge of orthographic regularities, or spelling patterns, says Nicole Conrad, professor of psychology at Saint Mary’s University in Halifax, Canada, who was not involved in the work. Although it’s a leap to say the observed patterns indicate literacy skills, she says, it “certainly shows that they are learning something that might be helpful for later reading.”

Every participant had used a letter board to communicate for at least a year prior to the study, and most had been in speech therapy for an average of almost 16 years, Jaswal’s team reported. “They have some familiarity with letters and how they go together. And that’s what we’re seeing on the task,” Conrad says. “It is interesting to show that can happen without explicit instruction.”

N

one of the participants could communicate effectively through speech. Their individual abilities “ranged from not at all to a few word approximations to limited phrase speech,” the study states.The study did not include detailed descriptions of the participants’ speech ability or any information about their receptive language ability, says Stephen Camarata, professor of hearing and speech sciences at Vanderbilt University, who was not involved in the work.

“If I tried to replicate this study, I wouldn’t necessarily know who to include,” Camarata says. “But overall, I think it’s credible. And I feel like they made a good-faith effort to really do this well.”

Jaswal did not assess receptive language skills because he could not identify a “measure that is quick, easy to administer, and which I can be confident provides an accurate indication of a nonspeaking autistic person’s receptive language ability,” he says.