Social development remarkably similar in monkeys, people

Eye-tracking studies cement monkeys’ promise for studying autism and related conditions.

Like human babies, infant rhesus macaques spend more and more time looking at the eyes of others as they get older. They also show a keen interest in members of their own species from a young age.

There are some species-specific quirks, but overall, these unpublished results from eye-tracking studies cement monkeys’ promise for studying autism and related conditions. Researchers presented the unpublished findings yesterday at the 2017 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in Washington, D.C.

The work is part of a larger effort by scientists at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, to characterize social development in the monkeys. The animals are all housed at the Yerkes National Primate Research Center in Atlanta.

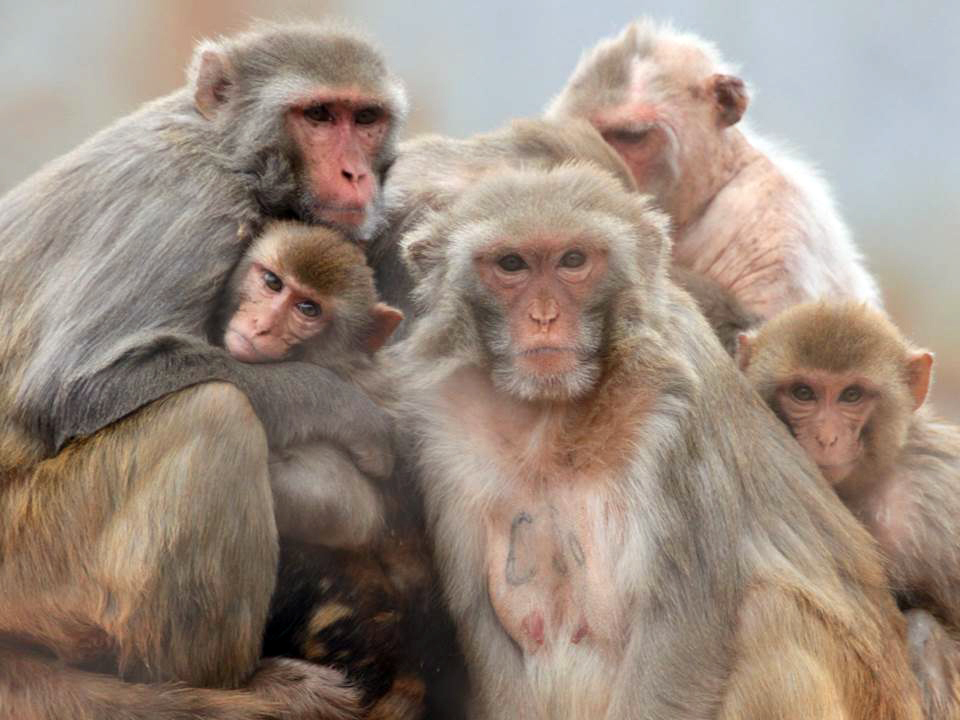

Rhesus macaques are native to South and Southeast Asia. They live in troops with complex hierarchies and strong social bonds.

“They are so similar to us,” says study co-leader Mar Sanchez, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Emory. “That’s why they are so important as a model.”

The researchers tracked the eye movements of 36 male macaques while they watched videos featuring another macaque. They tested each monkey 14 times between 1 and 21 weeks of age.

A previous eye-tracking study showed that between ages 2 and 9 months, human infants steadily increase the proportion of time they spend looking at the eyes in an image of a face1. Their interest in eyes dips around 9 months before increasing again around 18 months.

That study also showed that this development is different in babies later diagnosed with autism: Their interest in eyes simply declines steadily from 2 months of age.

Macaque infants show a pattern similar to that of typical babies, the researchers found — except their wavering interest occurs over the course of weeks, not months, reflecting their faster development. Macaques between 1 and 6 weeks old are increasingly interested in the eyes. Their attention flags a bit between about 8 and 18 weeks before picking up again.

Overall, monkey infants pay somewhat less attention to the eyes than human infants do, says Arick Wang, a graduate student in study co-leader Jocelyne Bachevalier’s lab at Emory, who presented the work. But their pattern of development “closely parallels humans’,” Wang says.

Eyes have it:

Monkeys and people obviously have differences researchers will need to take into account. For example, during the period when their interest in eyes diminishes, human infants become more interested in looking at the mouth. Macaque infants look more at areas of the face other than the eyes and mouth.

The researchers say the macaque infants may be looking at more at the ears. “Ears have a lot of social information for rhesus monkeys,” Wang says. For example, the animals flatten their ears when they make a grimace of fear. The researchers plan to analyze the eye-tracking data again to look specifically at the ears.

To get the infants to hold still enough for eye tracking, they built a kind of monkey recliner. They anesthetized the mother of the infant to be tested and placed her in the recliner, then put the baby on top of her chest.

“As long as you keep the baby on the mother, the baby is happy as a clam,” says Sanchez.

Sanchez is being modest: The approach is more challenging than it sounds.

Takeshi Murai, a postdoctoral researcher in Melissa Bauman’s lab at the University of California, Davis, gestures toward a photo of the setup in the poster Wang presented. “We tried that,” Murai says, wryly. “It didn’t work for us.”

On Sunday, Murai presented a poster describing the Bauman lab’s approach to working with macaque infants: a modified version of the box the researchers use to transport young monkeys when they separate the infants from their mothers for behavioral testing.

The box is small enough to ensure that the monkeys will remain reasonably still, and has a small window that the animal can look through to see the screen.

With this approach, the researchers collected eye-tracking data from 10 young macaques, tested six times each over the course of two months, while they watched videos of other monkeys or nature scenes. They found that infant macaques between 1 and 3 months of age are already more interested in social videos than in nature videos that don’t feature any monkeys.

Trusted face:

The Emory researchers also used eye tracking in 16 of the young macaques as the monkeys looked at paired images of human faces alternating with pairs of macaque faces. In each pair, one face has a ‘trustworthy’ appearance and the other an ‘untrustworthy’ one.

Many studies have shown that characteristics such as relaxed eyebrows and a slightly upturned mouth cause people to perceive faces as trustworthy. Arched brows and downward-pointing corners of the mouth give off an untrustworthy vibe.

There’s no standard for what macaques perceive as trustworthy or untrustworthy faces, says Jacqueline Steele, an Emory University undergraduate in Sanchez’s lab who presented some of this work. “We had to extrapolate,” she says.

The researchers selected photos of monkey faces that display characteristics similar to those of trustworthy or untrustworthy human faces, says Zsofia Kovacs-Balint, a postdoctoral researcher in Sanchez’s lab who supervised the study.

By the time they are 4 weeks old, the monkeys prefer looking at monkey faces to human faces, the researchers found. They also prefer trustworthy to untrustworthy monkey faces.

The researchers also scanned the brains of 21 monkeys seven times between 2 and 24 weeks of age. (The monkeys were anesthetized during the scans.) The scans showed that the trajectory of the infants’ social development matches that of their brain development.

“Changes in connectivity are matching developmental milestones,” says Zeena Ammar, a graduate student who worked on the project with Sanchez and presented this work yesterday.

For example, the monkeys’ social circuits strengthen around the time the infants wean and begin to spend more time away from their mothers and with peers.

For more reports from the 2017 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting, please click here.

References:

- Jones W. and A. Klin Nature 504, 427-431 (2013) PubMed

Corrections

This article has been revised from the original. It has been modified to correct the numbers of monkeys included in different parts of the study. It has also been revised to reflect that the researchers selected photos of monkeys faces resembling those of trustworthy or untrustworthy human faces, rather than digitally manipulating the photos to appear so.

Recommended reading

Expediting clinical trials for profound autism: Q&A with Matthew State

Too much or too little brain synchrony may underlie autism subtypes

Explore more from The Transmitter

Mitochondrial ‘landscape’ shifts across human brain