When autistic and non-autistic people look at photographs depicting social scenes, they generally look at faces first and then let their eyes wander to other parts of the image. After a few seconds, neurotypical adults are likely to return their gaze to the faces, but autistic people are not, according to a new eye-tracking study1.

The findings may help explain why people with autism tend to spend less time overall looking at faces than non-autistic people do: It’s not that they are uninterested in faces, but that social stimuli may not capture their attention in the same way.

Previous studies have examined how certain factors, such as a person’s ability to learn from or process different stimuli, affect social attention in autism, but few have evaluated how ‘looking patterns’ change over the course of an experiment or with age.

“This study goes a long way towards us having some insight into that process,” says Rebecca Shaffer, associate professor of pediatrics at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital in Ohio, who was not involved in the study.

Based on their eye movements, neurotypical people seem to grow more interested in faces as they age, but autistic people do not, the researchers found. And the autistic people who had the most distinct pattern of eye movements also had the poorest communication skills.

The results show that “there is information to be gained” by analyzing eye-tracking data in this way, says lead investigator Emily Jones, professor of translational neurodevelopment at Birkbeck, University of London in the United Kingdom.

Social scenes:

Jones and her colleagues collected eye-tracking data from 650 autistic and non-autistic people aged 6 to 30 years taking part in the Longitudinal European Autism Project (LEAP), a multi-country effort to identify biomarkers for autism.

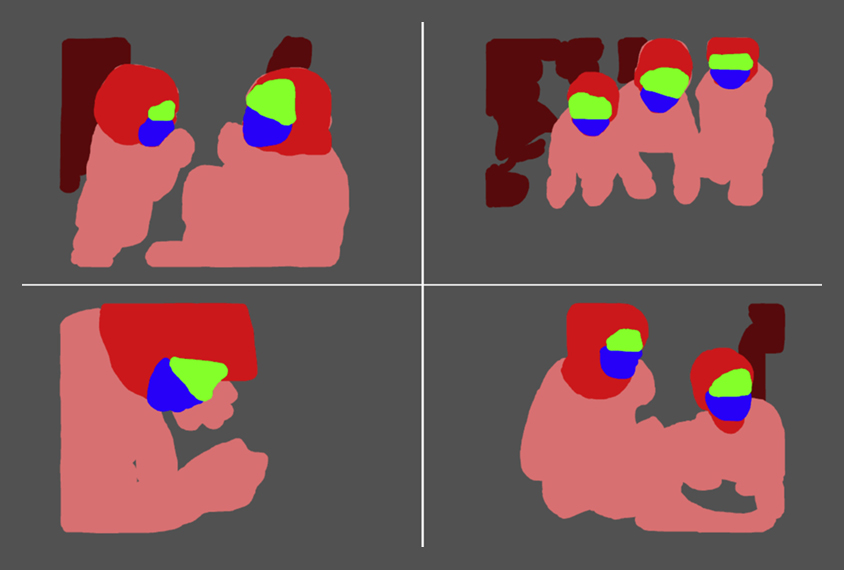

Researchers at six sites used an eye tracker to follow the participants’ gaze as they viewed a series of six randomly ordered photographs of social scenes — children playing or an adult interacting with a child and a toy, for example — on a computer screen for 20 seconds each. For each second, the researchers measured the proportion of time a participant spent looking at social elements of the photograph, such as a person’s face, head or hair, versus other parts of the scene, and they calculated how that ratio changed over time. They also examined how these looking patterns vary by age.

Autistic people of all ages are just as likely as their non-autistic peers to look at faces at the start of each trial, the researchers found, confirming previous findings that autism does not affect someone’s ability to detect and orient to faces2.

But as time passed, the groups differed in where they looked: After scanning other elements of a scene, neurotypical adults ultimately returned their attention to the faces, whereas neurotypical children and autistic people of all ages were less likely to do so. The study was published in Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging in September.

The results suggest that two different mechanisms drive the early and late looking patterns, and autism affects only the latter, Jones says.

By looking at individual differences, Jones and her colleagues found that autistic people with the most atypical looking patterns had the poorest adaptive communication and socialization skills, as measured by a test called the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales.

Though preliminary, that finding suggests that better communicators are more likely to become “experts” at faces over time, and therefore are more likely to devote attention to faces as they age, says study investigator Teresa Del Bianco, a postdoctoral researcher at Birkbeck, University of London.

The idea that communication skills can alter patterns of social attention is in line with another 2020 study, which found that once toddlers begin learning how to talk, they change which parts of a face they focus on3.

Eyeing the future:

“The million-dollar question in our field is: Why? Why is selective attention, or top-down attention, in autism so poor when it comes to social stimuli, like faces?” says Katarzyna Chawarska, professor of child psychiatry at Yale University, who was not involved in the work.

Though the researchers hint at some answers, the study was limited by the fact that it is only observational, she says. It was not designed to test hypotheses that might explain the mechanisms at play.

Moving forward, Jones and Del Bianco plan to study whether there are any sex differences in the patterns of social attention for people with and without autism. They also want to use their eye-tracking analysis method on data collected from people viewing videos of social scenes, which will better replicate looking patterns in the real-world, Del Bianco says.