Simon Baron-Cohen: Theorizing on the mind in autism

Few scientists have a career that spans as wide a spectrum in autism research as Simon Baron-Cohen, professor of developmental psychopathology at the University of Cambridge in the U.K. And fewer still garner effusive compliments from those who don’t agree with them.

One of the key concepts in autism research — that people with autism have difficulties interpreting the actions and intentions of others — owes its existence to Simon Baron-Cohen, a British researcher and among the most provocative thinkers in the field.

So does the first screening instrument for the infant siblings of children with autism, which Baron-Cohen developed in 1992. And the controversial hypothesis that autism is a manifestation of the ‘extreme male brain,’ which, according to Baron-Cohen, explains why the condition affects four times as many boys as girls.

Few scientists have a career that spans as wide a spectrum in autism research as Baron-Cohen, professor of developmental psychopathology at the University of Cambridge in the U.K. And fewer still garner effusive compliments from those who don’t agree with them.

“He is extremely prolific and has been hugely influential, both in the U.K. and worldwide,” says Francesca Happé, professor of cognitive neuroscience at King’s College London.

Given that Happé and Baron-Cohen are on opposite sides of one of the most controversial debates in autism — the decision to merge Asperger syndrome into the autism spectrum in the forthcoming edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders — the compliment is particularly weighty.

False beliefs:

Shortly after graduating with a master’s degree in human sciences from the University of Oxford in 1981, Baron-Cohen worked as a teacher in a small school for children with autism.

He was fascinated by the children, who showed clear signs of intelligence but at the same time appeared oblivious to normal rules of social interaction.

“These puzzling behaviors made me want to explore the disconnect between intelligence and social skills,” Baron-Cohen says.

The job led him to a Ph.D. at the Medical Research Council-funded Cognitive Development Unit, under the supervision of the pioneering autism researcher Uta Frith.

“Simon was one of those rare students who could make a success out of a rather sketchy idea which still had many question marks,” says Frith, professor of cognitive neuroscience at University College London. “He impressed me with his willingness to design his own test materials and to work hands-on with children.”

At the time, theory of mind — the ability to attribute mental states to others and interpret their actions — was a new concept, and it was thought that mind blindness, or the lack of theory of mind, might be the underlying cause of some aspects of autism.

Baron-Cohen and Frith recruited 4-year-old children with autism to test this idea. They showed the children a scenario involving two dolls. In the scenario, one of the dolls places a marble into her basket and leaves the scene. The second doll then moves the marble into her own basket. The researchers then ask the children where the first doll should look for her marble when she returns.

Typically developing children and those with Down syndrome pick up on the plot very quickly, and realize that the first doll doesn’t know what has happened. But children with autism say the first doll should look for the marble in the second doll’s basket.

This landmark study provided the first evidence that theory of mind is defective or delayed in children with autism1.

“Baron-Cohen’s early research is the foundation of a whole field which has been growing exponentially in the last decade,” says Rebecca Saxe, assistant professor of cognitive neuroscience at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “It has transformed both autism research and treatment practice.”

Still, it didn’t go far enough for Baron-Cohen.

“In those early years we took a very narrow view of theory of mind,” says Baron-Cohen. “The mind blindness theory had something going for it, but it missed a lot, particularly the role of emotions.”

Essential differences:

In the late 1990s, Baron-Cohen began to explore the idea that the autism spectrum might be defined by sex differences. He developed the Empathy Quotient, a measure of the ability to identify with another person’s feelings.

Women generally score higher on the empathy scale, whereas men tend to score higher on the systemizing scale, a measure of the drive to analyze and construct systems that follow rules2.

Children with autism also tend to score low on empathy and high on systemizing, Baron-Cohen has found3.

Seeing this same pattern of results on psychological tests, Baron-Cohen in 1997 proposed the extreme male brain hypothesis4, which characterizes people with autism as hyper-systemizers — focusing more on systems and repeating patterns than on other people’s thoughts and actions.

“Initially people were wary of it because of the long history of sex differences being taboo in science,” Baron-Cohen says. “But increasingly, the research community is recognizing that we might need to take sex-linked factors into account to understand autism.”

To better understand the skewed sex ratio in autism, Baron-Cohen started measuring testosterone levels in amniotic fluid taken from hundreds of pregnant women during routine testing procedures. The project is nearing its end; the children are about 10 years old, and Baron-Cohen’s group has studied around 500 of them so far.

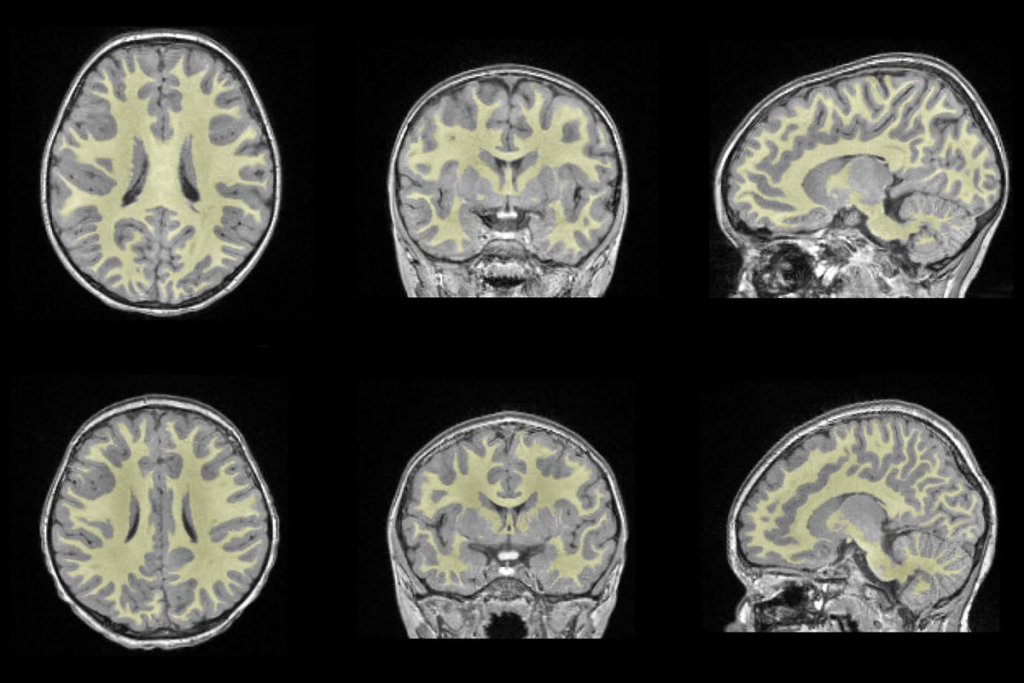

“We found correlations between early hormones and later behavior,” he says, “and are now inviting children to climb into the brain scanner, so that we can look for correlations in the brain.”

Many in the field are skeptical of this hypothesis, however. “It isn’t clear if the theory predicts that fetal testosterone is sufficient to cause autism or whether fetal testosterone levels interact with other markers of genetic vulnerability,” notes David Skuse, professor of behavioral and brain sciences at University College London.

Most of the analyses carried out by Baron-Cohen’s group are based on the mothers’ perceptions of their children’s behavior, and not on objective measures, Skuse adds.

In the past year, Baron-Cohen has taken on yet another controversial idea: that Asperger syndrome and autism should be merged under one diagnosis.

Baron-Cohen is a prominent critic of this decision, arguing that Asperger syndrome should remain a distinct diagnostic entity.

“My suggestion was that it is premature to delete it,” Baron-Cohen says. “I don’t think there have been enough studies comparing Asperger syndrome to other types of autism to be able to say there’s no difference.”

Still, he is quick to dismiss the idea that autism is a mental illness. Instead, he says, it is both a disability and a difference.

“The disability is in relation to social functioning and adapting to change,” he says. “But the child is processing information in an intelligent, albeit different, way, with attention to detail and an ability for spotting patterns.”

He compares the way in which autism is viewed today with how left-handedness once was, and says he hopes it will eventually be regarded as another variation.

“There are lots of different routes to adulthood,” he says. “The profile we call autism might just be one of those routes.”

References:

Recommended reading

White-matter changes; lipids and neuronal migration; dementia

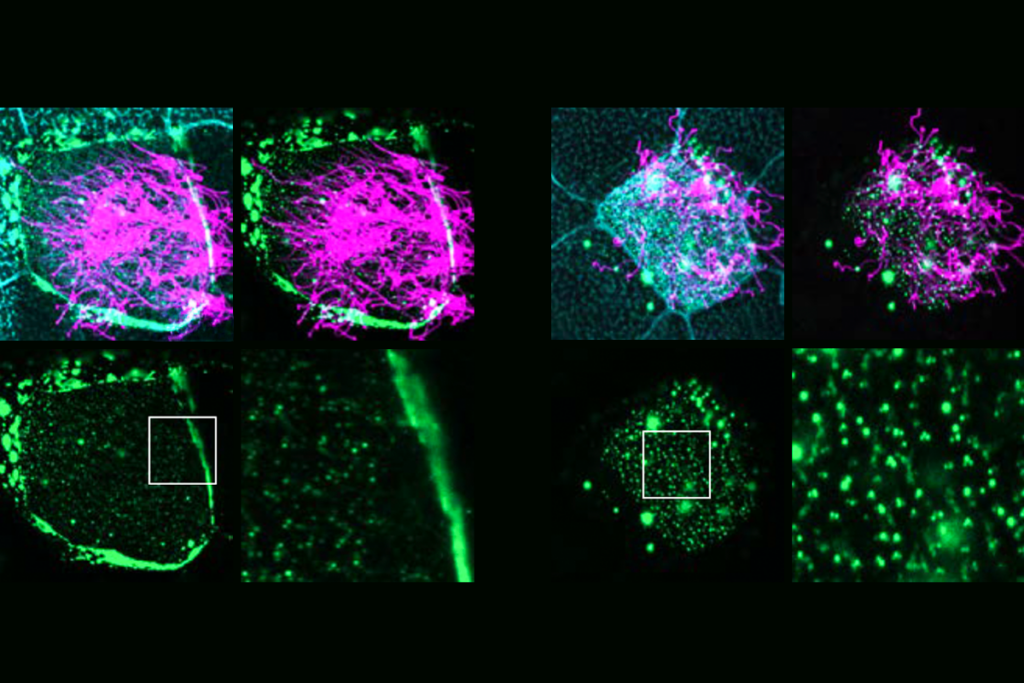

Many autism-linked proteins influence hair-like cilia on human brain cells

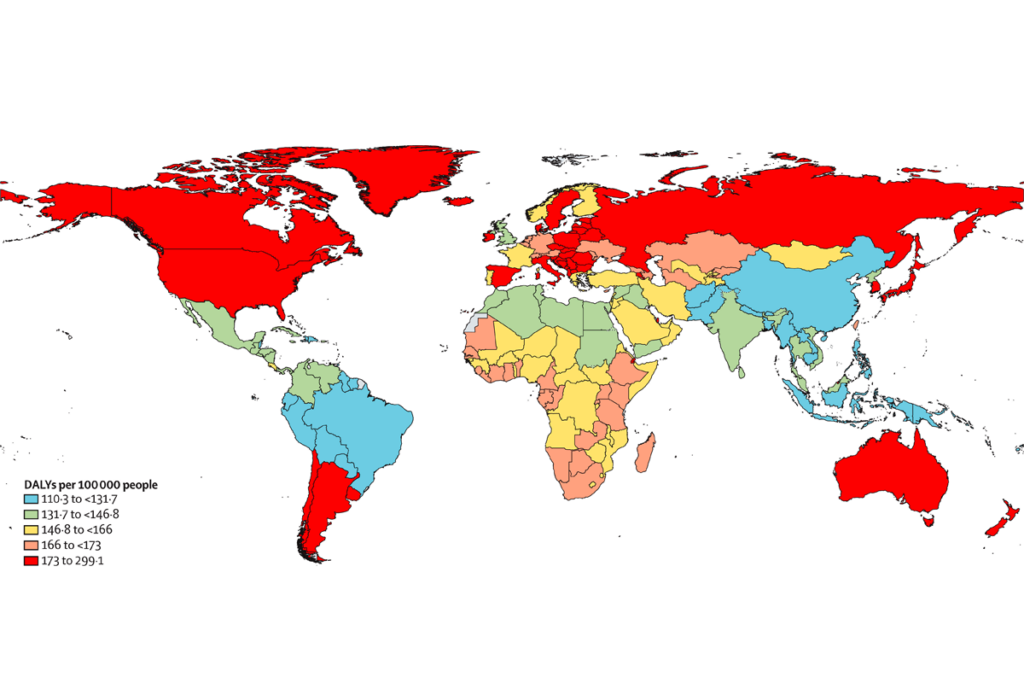

Functional connectivity; ASDQ screen; health burden of autism

Explore more from The Transmitter

David Krakauer reflects on the foundations and future of complexity science

Fleeting sleep interruptions may help brain reset