Siblings of autistic children may have distinct facial features

Siblings of autistic children, like those with the condition, tend to have faces that are more masculine than average.

Siblings of autistic children, like those with the condition, tend to have faces that are more masculine than average, according to a new analysis1. The analysis classified features such as a wide forehead and long nose as masculine.

The results in siblings follow from a 2017 study by the same team that found that autistic children, regardless of their sex, have more boyish faces than controls do2.

Family members of autistic children have long been known to sometimes have mild behavioral and cognitive traits of the condition — a phenomenon known as the ‘broad autism phenotype.’ The new work is the first to suggest that they may also show some physical traits of the condition.

“The brain and the face develop at the same time and in close coordination,” says lead investigator Andrew Whitehouse, professor of autism research at the Telethon Kids Institute in Perth, Australia. “Any biological factors that could affect the development of the brain could affect the structure of the face.”

The results jibe with the ‘extreme male brain’ theory of autism, which holds that autism traits are an exaggeration of stereotypically male traits, such as the tendency to look at things systematically rather than empathetically. The theory holds that these ‘male’ traits track with heightened exposure to testosterone in the womb.

Whitehouse and his colleagues reported in 2015 that boyish faces in typical people track with elevated testosterone levels in the womb at birth3. The new work suggests that the same may be true for autistic people and their siblings.

The results may reflect testosterone exposure — or they may reflect heritable genetic factors that influence both autism and facial structure, says Simon Baron-Cohen, director of the Autism Research Centre at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom, who was not involved in the study. “This would be important to investigate further,” he says.

Boyish looks:

Whitehouse and his colleagues captured 3D pictures of the faces of 40 girls and 40 boys with no family history of autism, all aged 2 to 12 years.

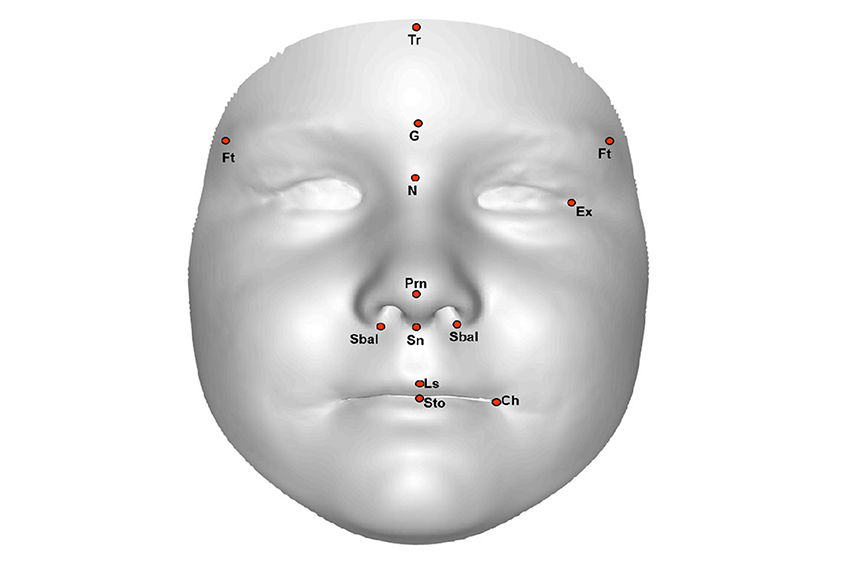

They used computer software to position 13 coordinates on the faces. (They used these same points to measure the masculinity of faces in the 2017 study.) They then measured the distance between 11 pairs of these coordinates.

An algorithm that uses these measurements to predict a child’s sex based on the masculinity of the child’s face classified the children with 95 to 96 percent accuracy, the study shows.

The researchers then used this algorithm to calculate a facial masculinity score for 30 boys and 25 girls aged 2 to 12 years who have siblings with autism. This score compares each child’s facial measurements with the average for that sex, calculated from a new set of 69 boys and 60 girls with no family history of the condition.

Brothers of autistic children have more masculine faces than the average for boys, the researchers found. The same is true for sisters. The findings appeared 16 January in Translational Psychiatry.

The sisters’ faces are not as masculine as those of the autistic girls in the 2017 work, whereas the brothers are not significantly different from autistic boys. This suggests that brothers of autistic children show this masculinization effect more than sisters do, Whitehouse says.

Still, it is unclear whether the masculinity seen in the siblings is related to the broad autism phenotype, says Tayo Obafemi-Ajayi, assistant professor of electrical engineering at Missouri State University in Springfield, who was not involved in the work. “It would have been helpful if [the researchers] had included data on other known and established traits of autism that could have been measured,” she says.

Whitehouse says his team is analyzing the facial masculinity of autistic children’s parents to better understand whether the trait is heritable or reflects children’s testosterone exposure in the womb. They are also measuring the facial morphology of 1-year-old children to determine how early facial masculinity becomes apparent.

References:

Recommended reading

New organoid atlas unveils four neurodevelopmental signatures

Glutamate receptors, mRNA transcripts and SYNGAP1; and more

Among brain changes studied in autism, spotlight shifts to subcortex

Explore more from The Transmitter

Psychedelics research in rodents has a behavior problem

Can neuroscientists decode memories solely from a map of synaptic connections?