Shape shifters

Breaking down the learning of new concepts into small steps may help people with autism retain new skills.

I’ve always been a global thinker, good at finding connections amongst random bits of information. But this strength has a corresponding weakness: Because I’m so focused on the big picture, details slip right by me.

According to the central coherence theory, people with autism have exactly the opposite problem. They are so focused on details that they are unable to coherently link information into a meaningful whole.

People with autism may recall all the details of a story, for example, without being able to remember the narrative. They are better at finding shapes embedded in complex images — the classic test for central coherence — but have difficulty generalizing and transferring concepts across different contexts.

A new study suggests that a strategy called dynamic assessment may help individuals with autism transcend their central coherence deficits. The strategy breaks down the learning of new concepts into small steps, which may be better suited to individuals with autism.

In this approach, researchers evaluate students not only before and after they learn a new task, but while they are engaged in learning it.

The researchers looked at 52 children with autism, between the ages of 8 and 12, who attended either mainstream or special schools. They used the Children’s Embedded Figures Test to measure central coherence in each child: The better the children are at finding the hidden shapes, the weaker their central coherence.

The researchers asked the children to arrange three-dimensional colored blocks on a wooden template. They had to copy the pattern from another template, so the task is a test of the ability to transfer a concept.

In addition to arranging blocks by color, height, and position, working with a teacher to complete the task allows children to use words such as top, bottom, left, right, same and different.

All of the children in the study did better when they worked with a teacher. However, children who showed evidence of weak central coherence had difficulty repeating their success without the help of a teacher later on. Children of average or above-average nonverbal intelligence, however, were able to successfully complete the task again without the help of a teacher, showing that they had indeed learned the task.

This finding suggests that children with autism who have average or high intelligence can compensate for their problems with weak central coherence, just as they can learn to overcome their weaknesses in theory of mind, the ability to understand others’ desires and beliefs.

Some public school systems have made great strides in effectively educating high-functioning children with autism alongside their unaffected peers. Studies like this one show they are on the right track in recognizing that children with autism are capable of effective learning — if they get the right kind of instruction.

Recommended reading

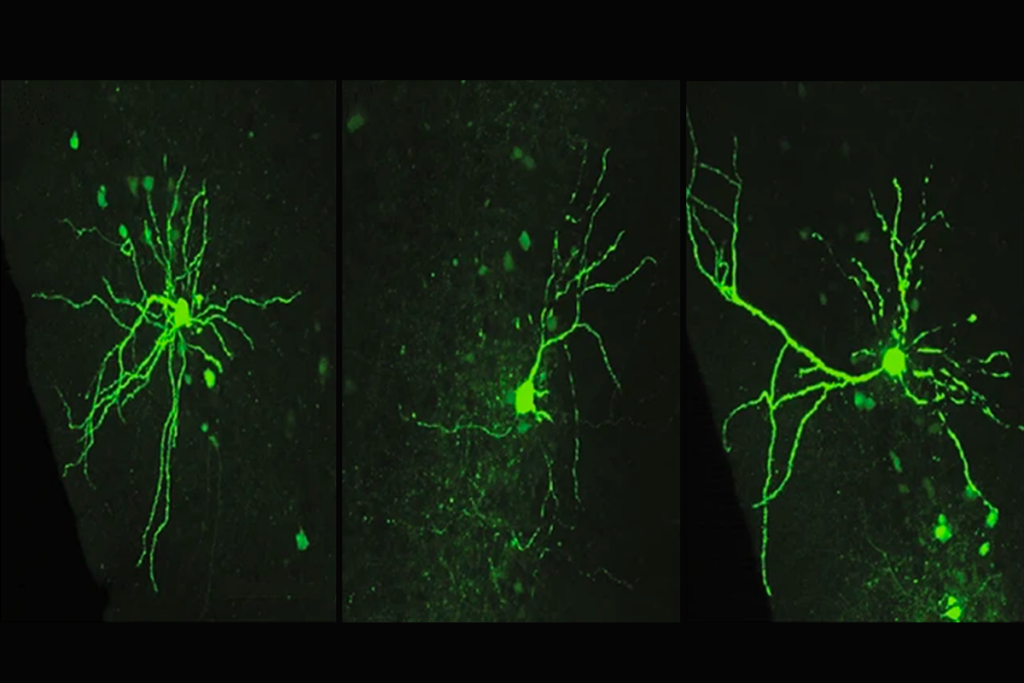

Assembloids illuminate circuit-level changes linked to autism, neurodevelopment

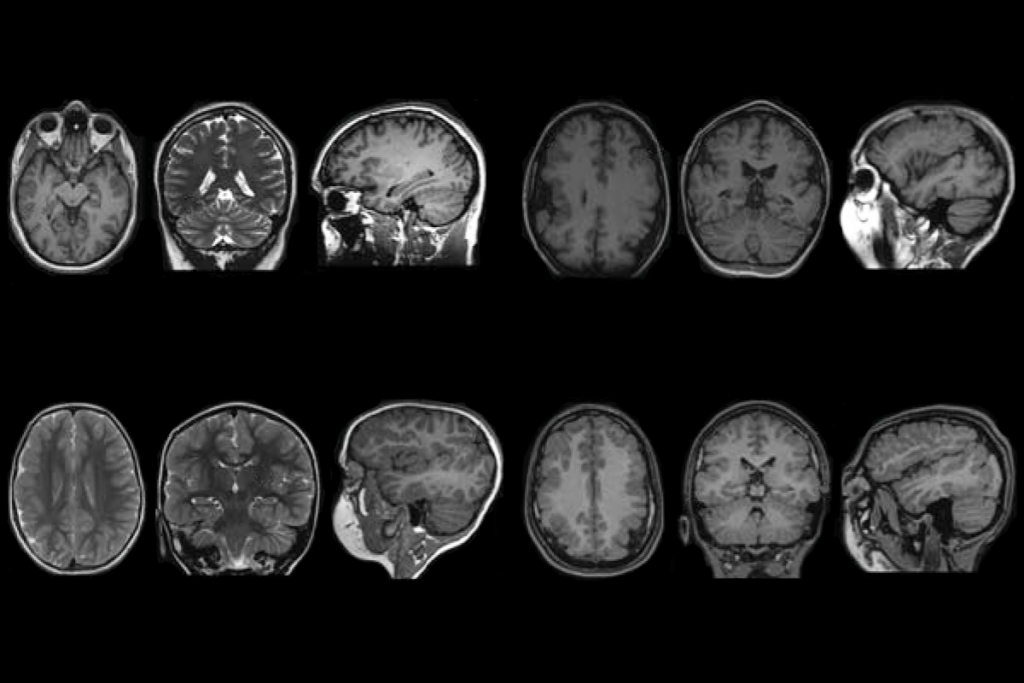

Impaired molecular ‘chaperone’ accompanies multiple brain changes, conditions

Explore more from The Transmitter

The non-model organism “renaissance” has arrived

Rajesh Rao reflects on predictive brains, neural interfaces and the future of human intelligence