Sex and other foreign words

People with autism fall in love. They marry. They even (gasp) have sex. Yet these deeply human needs have mostly gone ignored by scientists.

M

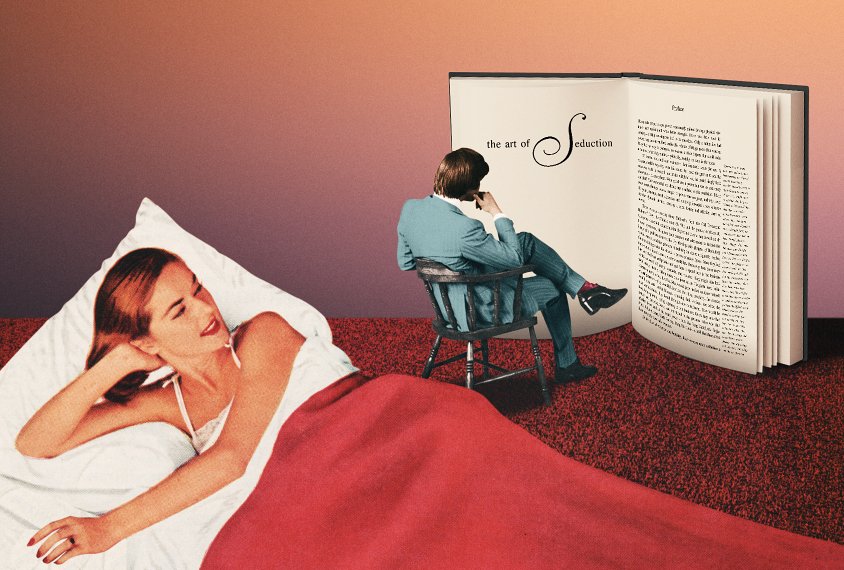

uch of what Stephen Shore knows about romance he learned in the self-help aisle of a bookstore near the Amherst campus of the University of Massachusetts.In college, Shore, who has autism, began to wonder if women spoke a language he didn’t understand. Maybe that would explain the perplexing behavior of a former massage student with whom he traded shiatsu sessions, who eventually told him she had been hoping for more than a back rub. Or the woman he met in class one summer, who had assumed she was his girlfriend because they spent most nights cooking, and often shared a bed. Looking back, other people’s signs of romantic interest seemed to almost always get lost in translation.

Shore turned to the self-help shelves to learn the unspoken language of love: He pored over chapters on body language, facial expression and nonverbal communication.

By the time he met Yi Liu, a woman in his graduate-level music theory class at Boston University, he was better prepared. On a summer day in 1989, as they sat side by side on the beach, Liu leaned over and kissed Shore on the lips. She embraced him, then held his hand as they looked out at the sea.

“Based on my research,” he says, “I knew that if a woman hugs you, kisses you and holds your hand all at the same time, she wants to be your girlfriend; you better have an answer right away.”

The couple married a year later, on a sunny afternoon in June 1990.

Relationship status:

S

hore was diagnosed with autism around age 3, about a year after he lost his few words and began throwing tantrums. Doctors advised his parents to place him in an institution. Instead, they immersed him in music and movement activities, and imitated his sounds and behavior to help him become aware of himself and others. He began speaking again at 4 and eventually recovered some of the social skills he had lost.Shore, now 55, recalls his classmates dating in middle and high school, but at the time he didn’t understand love’s allure. “I couldn’t really make sense out of it,” he says.

Society teaches people with autism from a young age that they are incapable of love, says Jessica Penwell Barnett, assistant professor of sexuality studies in the Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies program at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio. Barnett leads sexual education sessions for college students with autism. The stereotype of children with autism as cold, emotionless robots is painful, pervasive and entirely misleading, she says. “Some are very aware of this social representation — it’s like a cloud that hovers over all of their thinking about whether they can be in a relationship or whether another person is going to want to be with them.”

In fact, many people with autism both desire and sustain lasting relationships. “There’s no incompatibility with being on the spectrum and being in a romantic relationship, being in love, being part of a committed partnership,” Barnett says. Like Shore, an estimated 47 percent of adults with the condition share their home — and their life — with a romantic partner.

That doesn’t necessarily mean relationships are easy for people on the spectrum. Some features of autism, such as inflexibility, anxiety, sensory overload, difficulty communicating one’s own — and sensing others’ — personal needs and limits, would seem to lend themselves to relationship disasters. But that thinking is based almost entirely on conjecture. Scientists have been slow to study how and why people with autism form satisfying relationships. Until this decade, many adults with autism went undiagnosed, and those who had the social prowess to forge romantic relationships were considered “vanishingly rare,” says Matthew Lerner, assistant professor of psychology, psychiatry and pediatrics at Stony Brook University in New York.

As that stereotype falls away, researchers are scrambling to piece together a realistic portrait of romance and sexuality in people with autism. Through small studies and anecdotal evidence, they now know scant facts: that many more people with autism desire romantic relationships than achieve them; that autism features such as rigid thinking, anxiety and social awkwardness can create barriers to dating, sex and relationships; that gender variances, including non-binary genders and bisexuality, are more common among people with autism than in the general population.

Having identified some problems, researchers are still grappling with how best to help people with autism achieve lasting relationships. “This has become a sort of screaming priority,” Lerner says. “It’s one of the areas with perhaps the largest gap — I might go so far as to say it’s the area with the largest gap — between community interest and need, and empirical research.”

”"The only thing I knew to do was to play the role of a girlfriend." Amy Gravino

Dating dilemmas:

F

or most people, a healthy love life underpins psychological health and an overall sense of well-being. Depression and anxiety tend to ebb in women with satisfying relationships.Scientists say these same benefits apply to people with autism — and when romantic relationships are lacking, a key piece of social and emotional health goes missing, too. That can beget a sense of isolation: Depression and anxiety are more than three times as common in adults with autism as in people without the condition. “There is a big problem with loneliness in this population,” says Katherine Gotham, a clinical psychologist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee.

Step one in solving this problem: Dating.

The intricacies of dating — striking up a conversation with a stranger or trying to gauge another person’s interest based on body language or facial expressions, for example — aren’t specific to people with autism, but they’re more difficult for people with the condition to navigate. “We all have the same sorts of struggles, but folks with autism struggle even more,” Barnett says. “The differences are a matter of degree, not kind.”

Cultural factors can complicate courtship. In the United States, for example, dates typically unfold in noisy bars, busy restaurants or loud movie theatres. These environments can worsen anxiety and even be painful for people with sensory sensitivities.

Another complication is that most people tend to have a certain ‘type,’ whether it’s men with beards, for example, or tall women. But people with autism are sometimes unwilling to compromise, Gotham says. “I can think of five people off the top of my head who are frustrated because they don’t have what they want,” she says. The problem is that these people want not just someone they can connect with, but someone with a specific list of attributes. This rigidity can diminish dating prospects.

Dave, a single man living in Nashville, Tennessee, says that for most of his life he has felt anxious about interacting with women. (Dave requested that his last name not be used.) He has had a couple of romantic relationships — but what he really wanted was a girlfriend who resembled someone like Jennifer Aniston; he didn’t want to settle for anything less. He reasoned that because he didn’t have a girlfriend who fit that description, he must have been doing something wrong.

Dave attributed his struggles to a hearing impairment, his physical appearance and the scarcity of Aniston look-alikes in his area. Until he was diagnosed at age 45, he says, “it never occurred to me that it was autism.” After Dave was diagnosed, his therapist helped him hone his social skills. Before long, he had learned a few ground rules for casual conversation, such as taking turns speaking and choosing topics both people are interested in.

The nuance and subtlety of courtship can be especially confusing for people who have trouble recognizing social cues. It’s one of the most challenging social experiences that people with autism face: “Dating involves flirting, it relies on a lot of nonverbal behaviors,” Barnett says. “You don’t say what you’re thinking in the way that you’re thinking it.”

Last year, a team of researchers at University College London reported that women with autism tend to overlook subtle cues signaling a man’s interest, and mirror men’s flirtatious behavior without meaning to. About one-third of the women in the study said they didn’t notice platonic interactions escalating into something more sexually charged, so they often found themselves fending off unwelcome advances.

For Shore, too, the difficulty of recognizing social cues landed him in his first romantic encounter before he even realized what was happening.

After his first year of college, Shore began spending long hours with the woman he met during summer classes — talking, cooking and watching movies. “Then one day she tells me she really loves hugs and back rubs,” Shore recalls. “I remember sleeping over at her house, sharing a bed, and that was exactly what we did. Then she seemed to get pretty upset.”

During a lengthy conversation, Shore realized the woman had wanted to be his girlfriend. He wasn’t interested in dating, so the couple parted ways. But the experience stirred Shore’s curiosity about social cues. “That suggested to me that there’s this whole area of communication that we call nonverbal, which became fascinating to me,” he says. He started logging long hours in bookstores and libraries.

Girlfriends’ guide to romance:

W

hereas Shore read books to learn to detect a budding romance, Amy Gravino mostly relied on Hollywood to decode the rules of long-term relationships.Like many women with autism, Gravino often masked her social difficulties by adopting the mannerisms of neurotypical women. When she entered her first relationship at age 19, she mimicked the girlfriends she had seen in television shows and movies. “I didn’t know what in the world I was doing,” she says. “The only thing I knew to do was to play the role of a girlfriend — what I thought a girlfriend was supposed to do: I’m supposed to laugh at his jokes even if they’re not funny; I’m supposed to meet his parents.” Looking back, she says, “I didn’t realize that I just needed to be myself.”

Gravino says she found it difficult to forge a deep bond with her partner, in part because she didn’t feel comfortable being herself. The relationship stumbled over rocky terrain for a few months before he finally broke it off.

Her experience isn’t unusual, researchers say. For people with autism, developing a deep and lasting emotional connection is often more difficult than attracting a mate. That may be because a strong relationship depends on partners being both self-aware and aware of others, maintaining emotional stability and being able to learn from past experiences — three domains that prove challenging for some people with autism, Lerner says.

The condition doesn’t necessarily prevent children from forming deep friendships, as Lerner’s team found last year after analyzing the literature — a total of 18 studies — on friendships of boys with autism. But it may constrain the depth and closeness of those friendships — a finding that doesn’t bode well for romantic relationships later in life.

Relationships between a person with autism and a neurotypical person often falter over a specific problem: ‘able-ism,’ an unconscious or overt bias toward people deemed socially or physically ‘able.’ It can be difficult for a neurotypical partner to “understand what it feels like to exist in the world as a person on the spectrum, and be respectful of that and see [their partner] as a whole person,” Barnett says.

Unsurprisingly, long-term relationships are sometimes easier to navigate when both partners have autism. Barnett’s research suggests people on the spectrum are often accepting of each other’s quirks — a craving for deep touch, say, or no touch at all. “They felt that their relationships were higher quality when the partner was on the spectrum; they felt like their partner really got them,” she says. These observations jibe with those from a study of 26,000 adults with autism and 130,000 controls in Sweden, which found that most people with autism prefer partners on the spectrum.

The people with autism who form successful long-term relationships are the ones who have learned to negotiate arrangements that respect their needs — whether a prolonged period of quiet time after work, a relationship with cuddling but no sex, or even a sparsely decorated home that forestalls sensory overload.

Shore’s first relationship lasted a little more than two years. His second ended after just six months, when he discovered that his girlfriend liked to fall asleep to rock music. Shore, who had studied music education in college, found the music too distracting. The couple’s incompatible sleep preferences broke their relationship.

Touchy subjects:

B

eyond dating and love, sexual satisfaction — alone or with a partner — is important to well-being. But only a smattering of studies have explored the nature of sexual experiences of people on the spectrum. “Sexuality isn’t taboo in the research community, but it’s still kind of the last topic to the table — which isn’t really fair because it could be key to understanding quality of life and emotional health in people with autism,” Gotham says.

Shore says in his experience, there are two hurdles for a person on the spectrum to be sexual. The first is noticing a partner’s interest in sex. When a date made sexual advances, he often missed them. Once he caught on, a second hurdle appeared: He enjoyed sex but found the sensations overwhelming. Often his girlfriend would have to remain still while he waited for the sensations to pass.

The sounds and sensations of physical intimacy can overwhelm some people with autism. In a 2015 study, Barnett found that for some women with autism, these sensitivities manifest as vaginal muscle spasms, known as vaginismus, that make penetration painful or impossible. “Since [penetration] is considered the default for heterosexual sex in our population, some of them felt the obligation to provide sexual pleasure to their partners, but they also felt this painful coitus,” Barnett says.

Some women with autism don’t realize vaginismus is a common concern and may consider it a personal setback. Instead, she says, they need to use explicit language to describe their discomfort. “Sometimes you just have to say, ‘Vaginal sex just ain’t going to be our thing,’ and negotiate other activities that you can do for sexual pleasure and release.”

That may be easier said than done, however. In the University College London study, the researchers found that many women struggled to articulate their sexual desires and limits. Half of the women said they had acquiesced to unwelcome sexual encounters because they wanted to feel accepted, to receive affection or because they thought they were obliged to perform sexually in a relationship. These patterns also hold true for many neurotypical women, but women on the spectrum may be even less likely to stand up for themselves.

Healthy sexuality draws upon three factors — positive psychological and physical function, a supportive view of self and a strong knowledge base — says Shana Nichols, director of the ASPIRE Center for Learning and Development in Long Island, New York. The first factor comes naturally to people with autism who feel positive about their sexual function. And men with the mildest features of autism report the highest levels of sexual desire, performance, satisfaction and assertiveness, particularly when in a relationship.

The second has to do with self-acceptance and self-love: For some people with autism, romance could promote that positive view of self; for others, it may ultimately lead to the conclusion that life is best lived alone. About five years ago, Dave enrolled in ballroom dancing classes and began to practice interacting with women. Now he says he feels comfortable around his dance partners, and he enjoys socializing with them. “The key is to not worry so much about how someone else responds to me, but for me to be okay in how I’m responding to them,” he says. “Others see that I feel good about myself and it draws people to me.”

Dave insists he’s no longer actively looking for romance — he says he prefers to keep his dance partners at a safe, platonic distance. “I think one of the mistakes people make, including myself, is thinking they have to find somebody in order to be fulfilled,” he says. “A relationship with yourself is really everything.”

When it comes to the third factor — knowledge of sex — people with autism often have little information about sexually transmitted illnesses, contraceptives and sexual behaviors. What little they do know tends to be gleaned mostly from television shows, pornography or the internet. Neurotypical people, by contrast, generally learn about sex from friends, parents or teachers.

Dave says he used to think sex defined a relationship, and he wasn’t particularly interested in compromising on that point. “When you don’t have a lot of sexual experience, you tend to value that more than you actually should,” he says. “I thought that unless I was having those experiences, I wasn’t getting anything out of a relationship.” After working with his therapist, he understands that romantic relationships can mean different things, depending on each partner’s interests, desires and needs.

”“Sexuality isn't taboo in the research community, but it’s still kind of the last topic to the table.” Katherine Gotham

Dark side:

M

any parents feel compelled to educate their teenagers on the spectrum about sexuality, but need expert advice, according to a 2016 survey. Last year, researchers at Cardiff University in Wales uncovered one source of this squeamishness: Although studies of healthy sexuality are few and far between, there are more than 5,000 published studies linking autism to inappropriate behavior such as stalking, public fondling or sexual obsessions. A closer look at 42 of these studies reveals that those problems often arise in people with severe autism, perhaps due to difficulty sensing when other people are uncomfortable.Problematic behaviors also tend to crop up in children who are caught off guard by the physical changes of puberty, prompting the researchers to propose that sexual education may help stave off misconduct. Still, mainstream sex education classes may not address the needs of students with autism.

One program in the Netherlands, called Tackling Teenage Training, individualizes sex education for young people with autism. Enrolled teens have private counseling sessions every week for about six months, focusing on areas such as safe sex, respecting boundaries, and sexual preferences. A small clinical trial earlier this year found that the program helps teens with autism improve their sexual knowledge, build confidence and prevent inappropriate behaviors. One year after completing the program, teens still showed improvements in sexual knowledge, social behavior and problematic sexual behavior.

Sex education programs may also help reduce the alarming rates of sexual exploitation of people with autism.

The researchers at University College London uncovered a “shockingly high incidence” of sexual vulnerability: They found 9 of the 14 women in their study had a history of sexual abuse and 3 had been raped by a stranger. More than half of the women had felt trapped in an abusive relationship at some point in their life. The women also said uncertainty about social norms and trouble sensing ‘creepiness’ or red flags made them vulnerable to sexual exploitation.

Beyond protecting the vulnerable and deterring deviant behavior, these programs aim to guide people with autism toward strong, satisfying relationships.

Sometimes romance blooms without formal training, Nichols says, especially for people such as Shore, who are naturally motivated to notice subtle social cues. “It’s the greater awareness — that social awareness of others and also of themselves — that is really important,” Nichols says. “And the right fit of a partner is huge.”

Shore recalls the moment he realized Liu was the right fit. As he drove her across town one morning in the spring of 1989, Liu looked over at him and said she felt like they were already married. “I thought about it and realized she was right,” he says. In that moment, he says, they became engaged — without a diamond ring, a bended knee or other trappings of a traditional marriage proposal. “It was new territory, taking our relationship to a new level,” Shore recalls. “It was very exciting.”

Shore married a fellow musician, something he always expected he would do. But Liu grew up in China, which upended Shore’s long-held assumption that he would marry someone who shared his New England traditions and customs. He realized it didn’t matter at all that this expectation would not come to pass.

On the afternoon of 10 June 1990, about 150 friends and family members gathered in Cape Cod, Massachusetts, to celebrate Shore and Liu’s wedding. The couple exchanged vows roughly 40 miles down the coast from where they had shared their first kiss.

Corrections

An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that Amy Gravino, rather than her first boyfriend, ended their relationship.

Syndication

This article was republished in Scientific American.

Recommended reading

Prenatal viral injections prime primate brain for study

Common and rare variants shape distinct genetic architecture of autism in African Americans

Explore more from The Transmitter

BRAIN Initiative researchers ‘dream big’ amid shifts in leadership, funding

Neuroscience, BRAIN Initiative gain budget in ‘bad’ NIH funding bill